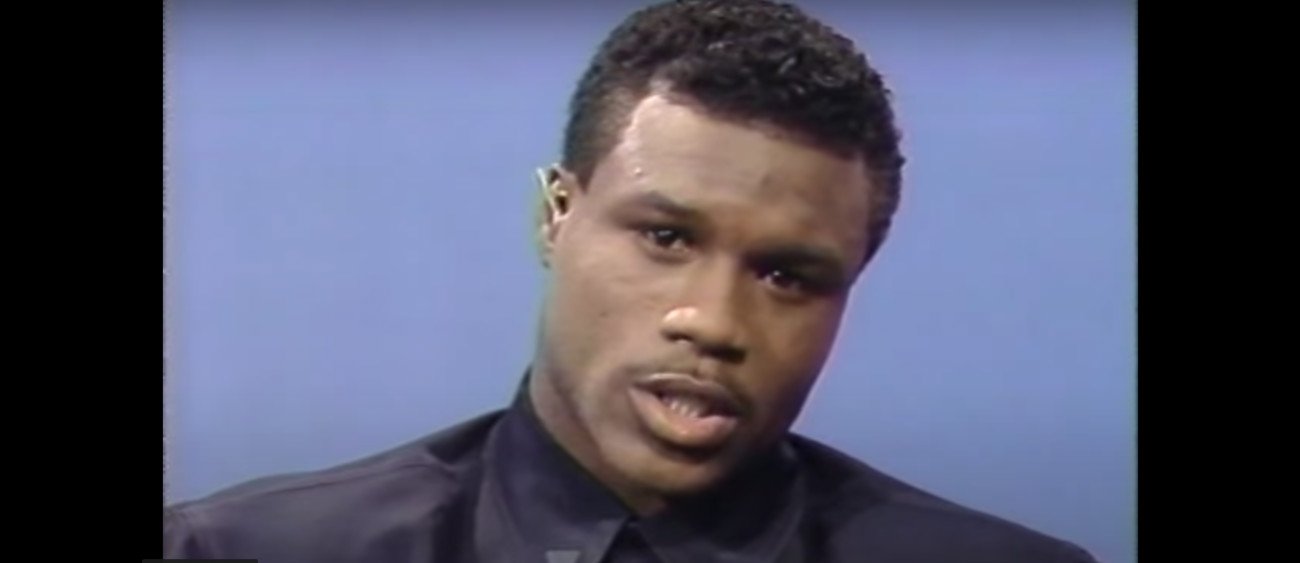

Whether you feel Meldrick Taylor was great or even an all-time great, there is no denying Taylor was special. Very special. The man who had hands so fast they could start a fire in his gloves, who had a heavyweight’s heart when he was, in reality, a natural 140 pounder, was too brave, too warrior-like for his own good.

Did Taylor have the fastest hands in all of boxing? Maybe he did indeed. How about the biggest heart in boxing in terms of recent decades? Again, maybe. Yeah, Meldrick “T.N.T” was very special.

By the time I saw him live and in the flesh, Taylor was still a talented fighter, but one who was refusing to accept the terrifying fact that he was not and never would be, the same man again due to what happened to him on the night of March 17, 1990. It was Philly heart, pride, and warrior-like tendencies against Mexican heritage – a refusal to lose, to let down the poor folks, who your sheer majesty gave so much hope to in the first place.

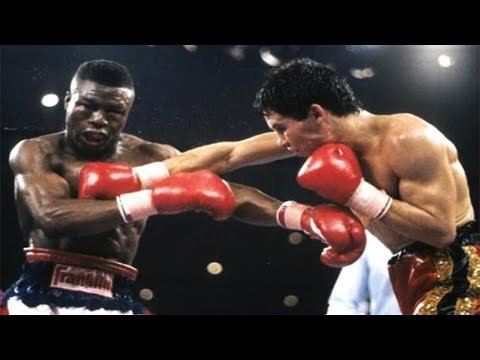

Taylor, some people say, could have made it a much easier fight. Box, move, land stinging punches, and get out; frustrate. But 23-year-old Meldrick Taylor wasn’t like that, he wanted to go to war, to BEAT his opponents, not just outbox them. He was a warrior. Chavez was too, and this collision of skills and differing styles ended up being settled one way: by who was the harder man. It was Chavez, with just two seconds remaining in what had been a super-fight display of everything from Taylor – speed, balance, courage, blazing speed of hand, desire, and an astonishing ability to take whatever came his way, to head and body – who elevated himself to super-human status.

A bleeding, battered, and confused Taylor, who had been let down by the chief cheerleader in his corner, literally did not know where to look. It was the greatest fight of the decade yet Mel had lost. And he had lost cruelly.

Inside a sold-out Earls Court Arena on Halloween night in 1992, Taylor entered the ring looking like a male porn star; his black leather shorts drawing lustful gazes from the passionate female fans in attendance. But Taylor, though still only 28, was no longer able to perform. Crisanto Espana ripped the WBA welterweight title from Taylor in eight rounds. It was amazing Taylor was there in the first place.

After being so badly hurt by the greatest Mexican fighter ever, Taylor for a while made us believe he wasn’t done, wasn’t damaged. A good win over the underrated Aaron Davis saw Taylor become a champion again, the 147-pound division seems to suit him well. But it was an illusion. Chavez had done deep, deep damage. We saw the fight and we read of its aftermath: a broken orbital bone, a ton of blood swallowed, bruised kidneys. Everything hurt but Taylor’s pride and unquestionable desire to carry on fighting.

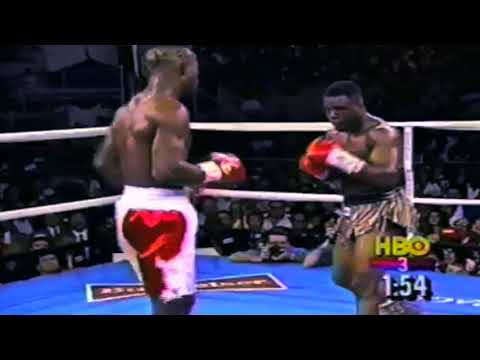

Against Espana, on the undercard of the Lennox Lewis-Razor Ruddock fight, Taylor grew old. He had piled on some years that May when an ill-advised move up to challenge Terry Norris for his 154-pound belt resulted in the quickest loss in Taylor’s career. Still, we thought Taylor would beat “the guy from Venezuela who fights in Ireland.” We were dead wrong.

But Taylor carried on. Already showing major signs of decline and, for those who were willing to listen hard enough, slurred speech, Taylor did manage to get his weight down and get a return go at an also past his best (but still formidable) Chavez. Once again, Taylor’s blend of speed, machismo, and stinging power made things hot for Chavez. Once again Taylor suffered a heart-breaking stoppage loss.

That should have been the end for the man who once had true, undisputed greatness within his grasp, yet Taylor – or a version of him – battled on for ten additional fights. Often against no-names, for poor money, Taylor won six and lost four. By the time he had his final fight, in July of 2002, Taylor neither looked like, sounded like, nor could fight like the almost perfect fighting machine we all marveled at in the 1980s and early 1990s.

It should never have ended like this for such a truly magnificent fighter/athlete/person. But it did. As such, the lesson of how playing it smart, rather than laying it all on the line in an effort at showing how much you really want it, can change a boxer’s life in so many ways. Though far less attractive to us hopeless fight fans and lovers of the dramatic hero show, a “boring” and/or “safety-first” fighter has a far greater chance of being able to live his post-ring life the way he wants to.

When the cheering has stopped. When the crowds have long since vanished. When only the hard-core boxing fans have a care.