The debate on whether boxing is the premium combat sport over mixed martial arts is generally a hollow argument dressed in ignorance. After all, they are two vastly different fighting disciplines only linked by their mutually destructive aim of rendering an opponent unconscious. You are unlikely to wage an impassioned discussion of the respective merits of Rugby versus American football, so why afford the column inches to the tedious boxing – UFC dispute?

Nevertheless, whilst direct comparison is misguided, this is not to say that the two sports can not learn something from observing the other. This is never truer than in the complacent world of fistic prizefighting: long in the tooth, resistant to change yet plagued by the same perennial problems.

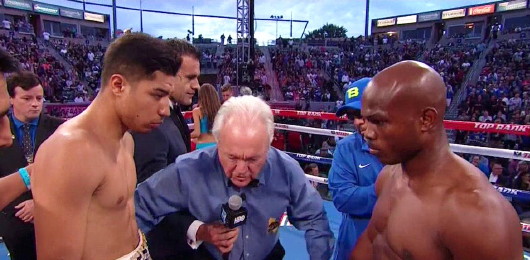

It’s a little harsh to crucify a man for one costly aberration, but unfortunately that is the fate of referee Pat Russell. This has all surfaced after a late gaffe by our Pat in Saturday night’s Welterweight title fight between Timothy Bradley and Jessie Vargas. Bradley, widely ahead on scorecards going in to the final thirty seconds of the twelfth stanza, was jarringly staggered by a stiff right from Vargas that left the pugilist they call “Desert Storm” careering and lurching wildly off into the ropes. It had been an entertaining but by no means breathtaking encounter, but now the HBO audience grew wide eyed with expectancy for a grandstand finish.

Vargas stormed in to finish the evidently groggy Bradley, rallying with bunches of malicious hooks. Bradley sought solace in a limp clinch, but ten seconds still remained for Vargas to apply the coup de grace! Within a blink of an eye the weathered and portly frame of Pat Russell was suddenly filling our screens, jumping in and sending Vargas back to his corner celebrating.

Had he stopped it prematurely in an astonishing come from behind victory? No, no. I’m afraid our Patty had dropped the ball catastrophically, mistaking the clapping which signifies ten seconds of the round remaining for the final bell. Ouch. As a boxing fan I winced for all involved and mourned the loss of what would have been a tumultuous finale.

Once more, despite the condescending tone, it is easy to have sympathy for Russell who now has a previously unblemished career memorably marred by this sure stay edit for boxing blooper reels.

The event ties in to an endemic issue which is blighting boxing at present. Of course Russell’s aberration could be perceived as a human error that could befall any premier referee. But in my opinion it wasn’t just a human error, rather more pertinently; it was an error from an old human.

If you were to compile a list of the attributes that you considered paramount to the armory of a high-skilled boxing referee it may read a little something like: loud-voiced for shouting instructions; physically strong for breaking fighters; mentally sharp for key decisions and acute hearing for discerning the signals of the bell and clappers throughout the contest. The pervasive complication permeating the current landscape of boxing refereeing is that these qualities do not correlate favorably with advancing years – yet, apparently, the profession of a boxing referee must remain a viable alternative to cashing in on your pension plan.

Just look at some of the revered boxing referees through the annals of time and a worrying pattern is glaring. Respected Puerto Rican boxing referee Joe Cortez was officiating major, landmark bouts up until the grand old age of 69, whilst the recent inductee to the Boxing Hall of Fame, referee Frank Cappuccino was a withered husk at 79. Hell, even the prestige referee of this era, Kenny Bayless, has reached retirement age at 65. Undoubtedly, these referees were legendary in their heyday, adding to the charismatic showmanship of the sport of boxing, but working the ring at 79? I’m all for the ‘right to work’ policies but the art of boxing refereeing is not the appropriate field for such legislation.

Admittedly, I know little about how contemporary boxing referees are vetted and accredited. Presumably there are medicals, cognitive tests and stringent assessments that have to be passed with flying colors. But whatever the current policy, it is far from watertight as proven by any sample population taken from the greying masses of boxing referee’s frequenting our screens at all major cards today.

By the late sixties, early seventies of a lifetime you have to expect deterioration of human faculties such as sight, hearing and physicality. By the same token, at this advanced age you have to expect an increasing amount of human error from boxing referees. Surely, this is common sense not a conclusion arrived at by any application of intensive medical schooling?

All of which brings me full circle back to the contention that there may be a little convention that boxing might like to glean from its very distant cousin, UFC.

On any fight card in UFC, the octagon does not house two size-able brutes ready for combat, but three. Referees in UFC match-up’s are fit to fight themselves, with great height, rippling muscles and a profile that screams power, typically at their disposal. You could argue that this is a necessity given that they are mandated to dive onto the mat and rip fighters off each other in moments of defenselessness, but the expectations between a boxing official and a UFC official are not that dissimilar – be firm and protect the combatants in knockout situations. Irrespective of this, UFC arbiters remain the anti Pat Russell’s of the refereeing world, physical presence supplanting the slowing relics favored in the boxing ring.

Watching a UFC fight you get an immediate sense of safety and tempered violence due to the impressive condition and formidable appearance of the referee. This appearance of safety may be an illusion, but remember it is not just the spectacle of combat sports that can be damaged by incompetent officiating but the pugilists themselves. Trusting an aged and wearied seventy year old to intervene as life-threatening blows are raining down on an incapacitated opponent is a sickening gamble that the higher authorities of boxing seem all too content to roll the dice on.

This whole standpoint on referees was highlighted to me most frankly when I attempted to show what I consider the greatest round of boxing (round nine of Gatti v Ward 1) to a close friend with a palate inclined to mixed martial arts, rather than the fistic variety. In a round that pulsed with courage, savagery and technique I felt sure that the celebrated footage would trigger a surge of boxing fandom from my mate, overthrowing his traditionally passing interest. As Gatti’s head recoiled from the mauling hooks of Ward I eagerly glanced over at my friend awaiting that slack-jawed awe that gripped the face of any first time viewer.

You know what I got? Instead of vicarious pleasure, I received a barrage of incredulous giggling.

“Why the giggles?” I asked with indignation as I leaped to defend boxing’s integrity from this unseemly chuckling.

“Why have they let an old age pensioner follow them round the ring?” He responded, still smiling with mockery.

I reset my eyes on the 73 year old Philadelphian Mr Frank Cappuccino who was traipsing listlessly round the ring after the two fighters. With a resigned exhalation I decided that through a lens of renewed clarity that it was, in fact, a ridiculous scene.

…….

Until progress is initiated and the role of governing the squared circle is offered over to broader, leaner, younger hands I am afraid that a central component of boxing’s inner workings will remain a laughing stock, or worse, a tragedy in waiting.

Michael McEwan