Burns finally gave Johnson his shot in Sydney

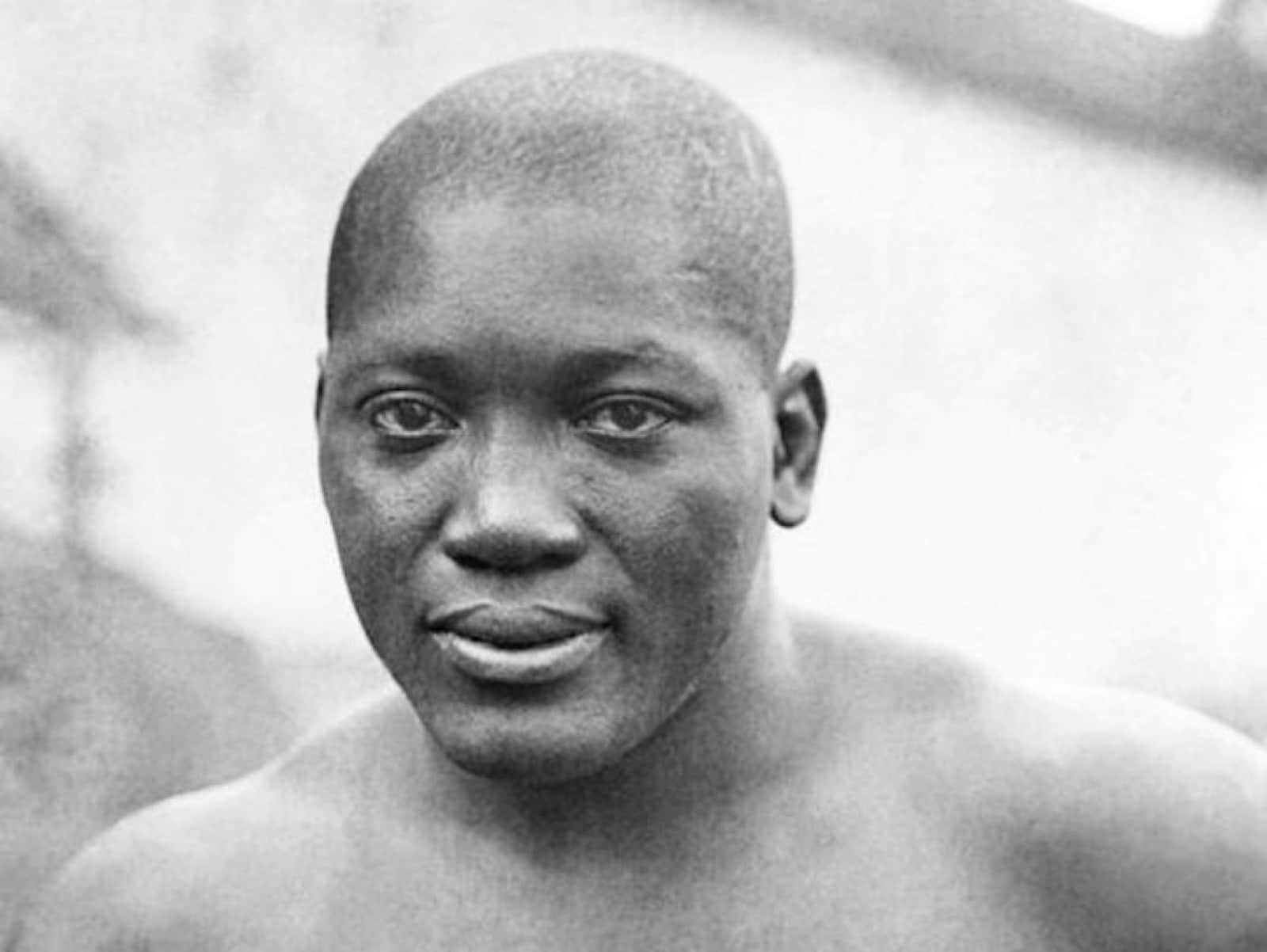

It was 113 years ago this week that fistic history was made in Sydney, Australia. Tommy Burns – the Hanover, Canada native who came into the world as Noah Brusso – finally put the heavyweight championship on the line against Jack Johnson, the 6-foot-1 Galveston “giant” who had chased him halfway around the world.

The fight took place on Dec. 26, 1908 – Boxing Day in the U.K. – at Rushcutter’s Bay in a 20,000-seat stadium built by promoter Hugh McIntosh for the occasion. It was notable for several reasons. First among those reasons was Johnson, the first African American to challenge for the world heavyweight title. Johnson won, of course, wresting the crown from Burns’ grasp after the police intervened in the 14th round and forced a stoppage.

The fight was also notable because Burns received the largest purse ever given to a boxing champion to that point. McIntosh, a wealthy caterer, offered the unheard of sum of 7,500 pounds to get Burns into the ring against Johnson.

The fight drew a packed house – with many turned away at the gate – with a gross of 26,000 pounds, so McIntosh made a nice profit on his venture.

Burns busy defending, Johnson busy chasing

Burns, who stood just 5-foot-7 but packed a knockout wallop in his right fist, had made 11 successful defenses of the title, including one draw, since winning it with a 20-round decision over Marvin Hart of Kentucky in February of 1906. Burns made his first four defenses in familiar territory, knocking out Fireman Jim Flynn, drawing in 20 rounds with Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, beating O’Brien soundly by decision over 20 rounds and then knocking out Australian Bill Squires in 1 round, all in the Los Angeles area.

After the KO of Squires, Burns became somewhat of a globetrotter. The Canadian, perhaps motivated by the heat he was drawing from Johnson and Johnson’s growing group of supporters, went overseas to Europe, putting the title on the line twice in London, twice in Paris, and once in Dublin in a dizzying span of seven months. Burns couldn’t shake Johnson, though. He was an ominous presence in the front row at Burns’ bouts, loudly berating the champion and issuing a renewed challenge at every opportunity. The National Sporting Club of London offered Burns 2,500 pounds to face Johnson but the champ wasn’t taking. He wanted 6,000 pounds to give Johnson a shot.

After knocking out Squires for the second time in Paris in June of 1908, Burns traveled to the Land Down Under and kayoed Squires once again on Squires’ home turf.

That bout took place in Sydney on Aug. 24. Just 10 days later in Melbourne, Burns met another Australian challenger, rugged Bill Lang, and knocked him out in 6 rounds. The hard-punching, 204-pound Lang gave the locals a thrill, sending Burns to the canvas in the second round before unceremoniously visiting the canvas himself a few rounds later. The ref for the Lang fight was none other than McIntosh, the far-sighted would-be promoter of the proposed Burns v. Johnson match, and negotiations for the much-anticipated bout began in earnest a short time later.

Burns finally came to terms with McIntosh, accepting the offer of 7,500 pounds to meet Johnson on Dec. 26 at the stadium at Rushcutter’s Bay that McIntosh would have constructed.

Burns was betting favorite

Burns entered the ring that morning – the bout was held at 11 a.m. Australian time – with a record of 42-3-8. He had eight straight knockouts to his credit, though the caliber of opposition had admittedly not been stellar. Burns weighed 168 pounds.

Johnson came into the fight with a 34-5-6 log, including victories over Flynn and former champ Bob Fitzsimmons (then just a shell of himself) in 1907. Johnson had also made ring appearances in Australia in 1907, knocking out Lang in Melbourne and Peter Felix in Sydney. Johnson was already a known commodity in Australia boxing circles, making the fight with Burns that much more of a local attraction.

Johnson’s world-class defensive skills and ring generalship had been honed in the fires of combat with the best black fighters in the world. Johnson engaged in memorable battles with the likes of Joe Jeannette, Sam McVae, Black Bill, Young Peter Jackson and Sam Langford. It was those battles, as much as any victories over white contenders, that prepared Johnson for the date with Burns in Sydney.

Burns was made the betting favorite but it was clear from the start he was no match for Johnson. The challenger had a 25-pound weight advantage and a four-inch height advantage and was faster, slicker and a harder puncher than the champ from Hanover.

One-sided affair

Johnson decked Burns in both the first and second rounds and was in control the entire way. As was his wont, the challenger talked to Burns throughout the fight, taunting him, and also carried on exchanges with some of the ringsiders.

Johnson could have knocked Burns out in an earlier round if he had pursued it but he didn’t. The Galveston challenger, gold teeth gleaming in the high Australian summer sun, was content to draw the fight out, perhaps as payment to Burns for having to chase the champ halfway around the world over the course of more than two years.

Burns was a battered man as the 14th round started. He was bruised around both eyes and had been bleeding from his nose and mouth since the eighth round. Films of the fight show Johnson going after his prey with vigor, battering him with lefts and rights until Burns was on his way to the canvas for the third time in the fight. The police stopped the filming of the fight just as Burns was falling.

The champ, brave and game to the end, got to his feet and took some more punishment before the police entered the ring and officially ended the matter. It didn’t go into the record books initially as a knockout, however. McIntosh, who was the referee, awarded the fight to Johnson on points.

Johnson is the champ!

The big news was that Johnson, a black man, was now the heavyweight champion. Other black fighters – notably George Dixon, Joe Gans and Barbados Joe Walcott – had won world titles at lighter weights but Johnson was the first black to even challenge in the heavyweight ranks.

“For the first time in the history of pugilism the heavyweight crown rests on a fighter of African descent,” is how one reporter started his account of the fight. Author Jack London, who was at ringside, famously called for Jim Jeffries to come out of retirement to remove the gold-toothed grin from Johnson’s face.

The search for the “Great White Hope” ensued and an ugly chapter in boxing history was about to be lived out.

Mike Dunn is a writer and boxing historian living in northern Michigan