He was for a time trained by Angelo Dundee, then by Archie Moore and Drew “Bundini” Brown. He fought no less than 11 world heavyweight champions. He defeated the great Earnie Shavers. He sent Gerrie Coetzee to hospital with missing teeth. He was the first man to take Mike Tyson the distance.

He is James “Quick” Tillis; aka “The Fighting Cowboy.” And he should have won at least a portion of the world title. Tillis was tough – teak-tough. Thrown in with just about anyone when it was pretty clear in the minds of the sport’s big players he would not become a champion, Tillis always came to fight; often being ahead in a bout, only to run out of gas and either lose a decision or be stopped late on. This happened to the converted southpaw from Oklahoma when he fought Marvis Frazier (decking Frazier early on, only to lose on points), Carl Williams (decking Williams twice early on, only to lose on points), Gerrie Coetzee (busting Coetzee up and knocking some teeth out, only to lose on points. A pattern had emerged.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PcaeLooNGZA

But when he was up, turned on and ready to fight, having been given sufficient notice, Tillis could hang with the best. It is his fight with Tyson – from this day back in 1986 – that Tillis is perhaps best known. By this stage of his career Tillis had failed in a 15-round title challenge of Mike Weaver, he had been stopped in a round by Tim Witherspoon (perhaps slipping on a wet spot on the canvas) and he had seen Dundee, Moore and Bundini leave him. Now looked after by Beau Williford, Tillis was looked at as a high quality journeyman type. He was better than that. And Tyson found out.

Totally unintimidated by the 19 year old, 19-0(19) Tyson, Tillis had a new weapon in his arsenal. Having grown sick and tired of growing sick and tired at the midway stage of his fights, Tillis, now aged 29, got himself checked out by the doctors. To his amazement, Tillis was informed of his severe allergy to both milk and eggs – these two essential ingredients in the classic fighter’s diet having been eaten for many years.

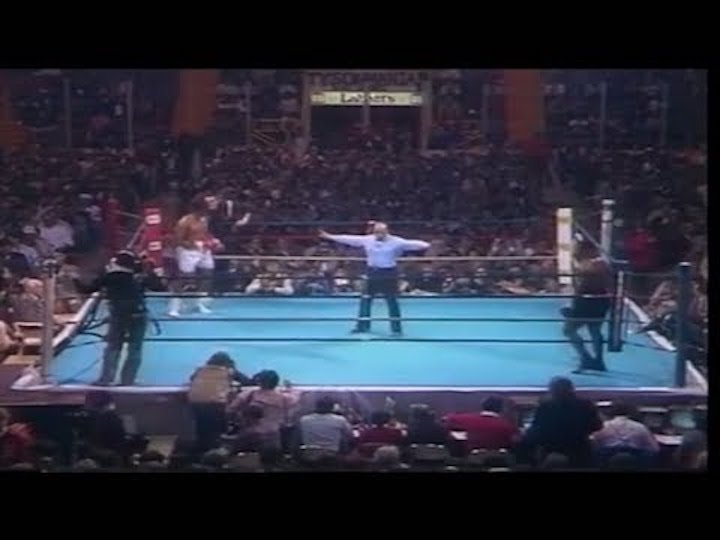

Having given them both up, Tillis felt a whole new man; one with a whole new burst of life and energy. Tillis showed up fit, strong and ready for Tyson. Boxing brilliantly during most of the fight, Tillis was up on his toes, he was effective at blocking Tyson’s shots and at making him miss, and “Quick” got Tyson’s attention many times. His right hand to the head crashing in on occasion, his swift uppercuts forcing Tyson to take a step back and recompose himself, Tillis was holding his own.

A silly mistake cost Tillis in the fourth round. Lunging at Tyson with a left hook that missed, Tillis was countered by a Tyson left hand and, his feet squared up, he went down. Unhurt and up quick and smiling, Tillis had blown any chance he had of winning the decision. In fact, at the end it was wide for Tyson on one card – 8 rounds to 2 (the crowd booing this score), and 6-4, 6-4 on the other two cards. To this day Tillis insists he won the fight.

What was remarkable was the way Tillis, who had faded in so many previous fights, had come on strong in the later rounds, banging with Tyson and more than getting his respect. Watching the fight today – something of an underrated near-classic – it really does show those people who think Tyson would have beaten the great Muhammad Ali how wrong they are. Sure, Tyson hadn’t yet peaked at the time of the Tillis fight, but Tillis was no Ali. Anyway, that’s another story.

Tillis gave Tyson the toughest fight of his career – and arguably one of the three or four toughest fights the peak (1986 to 1988) Tyson ever had. Tyson was sore afterwards and years later he was man enough to admit it.

Tillis fought on but slid into a permanent downward decline; being beaten by Joe Bugner, Frank Bruno, Evander Holyfield, Gary Mason and, in a painful fight that lasted less than a round, Tommy Morrison. Tillis retired in 2001, his career record a none too special looking 42-22-1(31).

James Tillis had a little of Ali’s speed and movement, he had a great chin, he had the old-school toughness the 1970s heavyweights had, and he had those three great trainers. But for whatever reason or reasons, “The Fighting Cowboy” never got off the dirt trail; he never reached the top of the mountain. He should have done so.

(check out Tillis’ excellent and utterly honest and revealing autobiography: “Thinkin’ Big” – a great read).