Matthew Saad Muhammad, perhaps the most entertaining light-heavyweight in boxing history, passed away over the weekend at the age of 59. Promoter J Russell Peltz, International Boxing Hall of Fame class of 2004, recalls his days with Saad.

Matthew: You Gave Us Everything You Had!

I was in my car Sunday afternoon in Pittsburgh with my wife, Linda, and our grand-children and we were on our way to see the Pirates play at PNC Park when the call came in over the car-phone speaker. It was Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, calling from Las Vegas, to tell us that Matthew Saad Muhammad had passed away the night before.

Eddie boxed several times for me in the 1970s and 1980s and we have a friendship based on mutual respect. Eddie has become a keeper-of-the-flame for the fighters of his era and in January, 2011, he and his wife flew from Las Vegas to Philadelphia to attend Bennie Briscoe’s funeral, something I will never forget.

Saad Muhammad, the orphan who became world champion, gave you your money’s worth every time out and he did it during the light-heavyweight division’s finest era. There is no greater compliment you can give an athlete.

The story goes that, when he was about 5, his older brother and he got separated on the Ben Franklin Parkway on their way to visit their grand-mother. Another version has it that his older brother was given instructions to abandon him there. A policeman found him.

Unable to identify him and getting no help from the youngster, the police turned him over to Catholic Social Services. He was named for St. Matthew and Franklin since he was found on the Ben Franklin Parkway.

A troubled child, Matthew spent time in the Youth Study Center as a teenager before one day wandering into Nick Belfiore’s Juniper Gym in South Philadelphia. That changed his life.

The young Matthew Franklin had 20 amateur fights and won the Trenton (NJ) Golden Gloves in 1973. He turned pro in 1974 under the management of William “Pinny” Schafer and Pat Duffy. Schafer was head of the Bartenders Union in Philadelphia and Duffy ran amateur boxing in the Middle Atlantic area and had an underground railroad to send kids to the pros.

Matthew was nothing special, despite winning his first seven fights, five by knockout. Those were wonderful days in Philadelphia and we were loaded with talent.

In the mid-1970s, the city’s hottest fighter was junior lightweight Tyrone Everett, who was managed by Frank Gelb, a good friend of mine. Tyrone’s brother Mike, also managed by Schafer and Duffy, wanted to join his brother in Gelb’s stable. Matthew didn’t want to be left behind again—sound familiar—so a deal was worked out early in 1975 and Matthew became a throw-in, something akin to a baseball trade for future rights to an unnamed player. It was the biggest steal since 1626 when Peter Minuit bought Manhattan from the Indians for a load of cloth, beads and hatchets.

Gelb, never one to baby his fighters, sent Matthew to Trieste, Italy where he upset future WBC light-heavyweight champ Mate Parlov, of Croatia, then to Stockton, CA, where he beat future WBC cruiserweight champ Marvin Camel, of Missoula, MT. Gelb was my kind of manager—he wanted to find out what he had.

Though Franklin lost the rematch to Camel in Missoula and boxed a draw the second time with Parlov in Trieste, Gelb knew what he had. In those days, fighters were not banned from television because they lost a fight here and there.

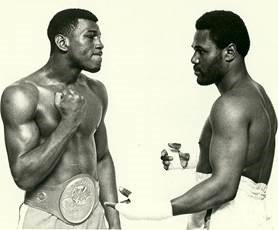

At the same time as Don King’s ill-fated US Boxing Championships on ABC-TV early in 1977, Don Elbaum and Hank Schwartz ran their own tournament on a network of small cable systems. The Elbaum-Schwartz tournament was far superior to King’s, but lack of funding doomed it after a handful of shows. The opening round in Philadelphia paired the young Franklin against Eddie Gregory (later Eddie Mustafa Muhammad). It was held at the old Arena in West Philadelphia and featured middleweights Vito Antuofermo vs. Eugene “Cyclone” Hart in the co-feature.

Franklin dropped Gregory in the first round and appeared to have won the fight after 10 rounds. Scores were 46-45, 45-44 and 46-44, all for Gregory, under the old Pennsylvania 5-point must system. I was at the fight and it could have gone either way. I believe the voting referee and both judges were from Philadelphia.

At the time, Franklin was more of a boxer than a puncher but he was so distraught over the decision that he decided to change his style and start slugging to take his destiny out of the judges’ hands.

His coming-out party was July 26, 1977 at The Spectrum for the vacant NABF title against another future light-heavyweight champion, Marvin Johnson, of Indianapolis, IN. I consider myself fortunate to have promoted the greatest fight I ever saw in person. It was two magnificent athletes exchanging bombs for 11 rounds. The judges were 1-1-1 between them before Johnson sagged to the canvas in the 12th round and the video of the fans going bonkers at ringside remains a cherished image on my DVD.

More Hollywood-like fights followed at The Spectrum. Matthew got off the floor to stop Billy “Dynamite” Douglas the next time and did the same early in 1978 when he went down on his face against Richie Kates, but got up and stopped Kates two rounds later. Today, some of those fights would have been stopped with Matthew the loser.

When our son Matthew was born in October, 1978, Matthew the boxer was convinced we had named him after our favorite light-heavyweight.

That same month, the 175-pound Matthew K0d Yaqui Lopez at The Spectrum in their first fight.

As always in boxing, trouble was brewing. Matthew was looking to sever ties with Gelb, who claimed to have an extension. Matthew said he had been tricked into signing a blank piece of paper.

At the pre-fight press conference for the Lopez fight, Matthew introduced me to Bilal Muhammad, later to become his official manager after a series of legal battles.

After he won the WBC world title in April, 1979, by again stopping Johnson, this time in Marvin’s Indianapolis backyard, Matthew Franklin became Matthew Saad Muhammad. Belfiore was jettisoned from the corner, to be replaced by Sam Solomon and Adolph Ritacco. Gelb got paid for several fights, but Bilal Muhammad was running the show.

Classic fights followed, promoted mostly by Bob Arum, then Murad Muhammad. It seemed like every one was a Fight-of-the-Year candidate, including the rematch with Yaqui Lopez in 1980 at the Playboy Club in McAfee, NJ, where Saad rallied from far back to win in 14 rounds.

Saturday afternoons in Atlantic City were festive-like every time Saad defended his title, be it against John Conteh, Vonzell Johnson, Murray Sutherland or Jerry Martin. He was always trailing on points and taking a beating, often bleeding, when he would rally to win.

It came to an end in December, 1981, at the Playboy Casino in Atlantic City. At the morning weigh-in for a 5pm fight against Dwight Muhammad Qawi, Saad was more than five pounds over the limit. It was unacceptable on his trainer’s behalf and Saad spent the morning running on the beach to shed the weight. He was a shell by the time the bell rang and Qawi battered him. Everyone waited for the late comeback, but it never materialized; he was K0d in the 10th round. Matthew was 27 years old and it was over.

It was more than the weight issue. The hard fights and the beatings had caught up to him and it showed in the rematch the following summer at The Spectrum when Qawi repeated, this time in six rounds.

He boxed on for another 10 years, losing to fighters he would have beaten with one hand years earlier.

Why do fighters fight too long—they need the money. In the late 1970s, early 1980s, Saad was making between $250,000 and $500,000 for some fights, but no one was looking out for his finances. He had bought a beautiful home in Elkins Park and it was decorated by one of the most expensive interior designers in the Philadelphia area. He did not own it for long time. He had a beautiful wife—she later left him.

Years later, he told me that those closest to him in boxing had borrowed money from him and never paid him back.

He was so broke he sold his championship belts, robes, trophies, everything he had earned in boxing, just to pay his bills. He lived in the basement of a friend’s home for a brief time around 1999. Neil Gelb, one of Frank Gelb’s sons, got Matthew a job with the city, but Matthew disappeared after 10 days “and I did not see him for close to 10 years after that,” Gelb said. Matthew also spent time in a homeless shelter.

Through all his down times, Matthew remained friendly and outgoing and he never lost his movie-star looks. At my Hall-of-Fame induction in 2004, seconds before my speech, he got up from his seat on the stage to applaud and salute me. When Linda and I were walking downtown about three or four years ago, he was riding in a car along Sansom Street and he jumped out to run over to say hello and hug us.

The news last week that he had been suffering from Lou Gehrig’s Disease and had a stroke was a stunner. But nothing compared to Eddie’s phone call Saturday.

We tend to exaggerate the heroes of our youth. I was in my late 20s, early 30s during Matthew’s heyday. Oh, if he only were around today!

When Bennie Briscoe passed away, I felt I had lost a piece of my heart. When Saad passed away, I felt I had lost a piece of my past.