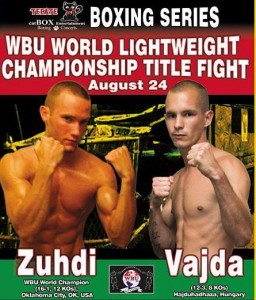

When WBU Lightweight Champion Noah Zuhdi (16-1, 12 KOs) steps in the ring against Hungarian challenger Gyula Vajda (12-3, 8 KOs) on August 24 at the Lucky Star Casino, he is not just fighting a sharp counterpuncher in his first title defense. He is fighting the litany of naysayers and people who subscribe to an archaic notion that a boxer has to be born and act a certain way in order to thrive in the sport.

When WBU Lightweight Champion Noah Zuhdi (16-1, 12 KOs) steps in the ring against Hungarian challenger Gyula Vajda (12-3, 8 KOs) on August 24 at the Lucky Star Casino, he is not just fighting a sharp counterpuncher in his first title defense. He is fighting the litany of naysayers and people who subscribe to an archaic notion that a boxer has to be born and act a certain way in order to thrive in the sport.

We know what real fighters are. Fighters are not practicing lawyers or attorneys. Fighters do not start training in their twenties. Fighters do not grow up geographically and socioeconomically in middle America. And certainly real fighters do not video chat with a wife and infant son every night while in training camp. Yet, Zuhdi is and does all of these things, and he has fought his way to the fringes of boxing stardom.

“Nobody has to fight,” Zuhdi told Eastside before his bout with the tall and crafty Vajda. “No matter what your background is, no one has to get beat up like a boxer does or train as diligently as a boxer does. Boxing is not forced upon people. You choose it because of a love and passion for the sport. Anyone who says otherwise is shortchanging the fighter. I have that competitive desire and passion for boxing.”

Beginnings

Zuhdi’s passion for the sport fueled a victory for the World Boxing Union (WBU) Lightweight Championship last year in what WBU executive Joe Louis Barrow II—yes, son of that Joe Louis—hailed as “the best fight I’ve seen in ten years.” Despite playing college basketball and starting boxing while in law school, the 30-year old always had a love for boxing.

“Even though I grew up the son of an amateur boxer (my dad),” Zuhdi explained, “it was actually my mom who first introduced me to boxing. She knew me and my interests and told me one night, ‘Come over here and watch this. I think you’ll like it.’ It happened to be a Mike Tyson fight. From then on, I knew this was a sport I wanted to follow. It was both beautiful and brutal inside the ring.”

His background and story may have more in common with fans than fighters, but the Oklahoma native chose to throw his hat into the ring and himself into the sport all while balancing family life and a burgeoning career in law. Boxing is not about where one is or what one is born into. Boxing is about who one is. Zuhdi elaborated, “To be a successful boxer, and I am not saying I’m this great success yet, you have to have it inside you. It’s inside what counts. If I get knocked down and can’t see straight, I’m doing everything I can to get back up. I don’t care: I have that competitive desire within me.

“I was 22 years of age and my basketball career was over, but I was too young to hang it up athletically. I still felt I had a purpose to do something while in my physical prime. I needed to compete. Having consumed all that there is about boxing in terms of fight tapes and books throughout the years, I thought to myself, ‘Why not give this a try?’ So, I did and haven’t looked back.”

A Step Back

While Zuhdi never looked back, he was forced to take a giant step back when he faced off with the unheralded Reymundo Hernandez and suffered the first loss of his career. Stunned by the loss but benefitted by the gift of hindsight, he knew that he could train as well as he wanted, but training for the specific opponent takes on a heavier importance. Zuhdi was unprepared for the local backlash as much as he was for Hernandez’s style.

“That surprised me,” Zuhdi commented. “That surprised me a lot. People, even some friends, were asking me if I was going to retire. It was like they were saying, ‘Okay, you’ve done enough. Now it’s time to go back to law.’ They didn’t understand that this wasn’t just some gimmick or hobby. I was of the mindset, ‘Hey, it’s just one loss. I’ve learned from it and am ready to go again.’ That’s one thing about me that might be different from other fighters: losing will not affect my pride. If I go into a fight knowing that I’ve done everything I could, done my best, then I am okay with the outcome.”

Still, in order to move on, the future WBU champion would have to endure many of the same hardships local or “club” fighters have to go through. The list is plentiful: Last minute opponents? Check. Having to face some goons and loons who tested positive for drugs? Check. Having local fighters call him out despite having never drawn a dime in sales in the past? Check. Getting offered fights on national television on a few days notice? Check. Dealing with shady trainers and promoters even though there’s not millions of dollars at stake? Check, check, check.

The career path of an unheralded fighter is a jungle—there is no easy or clear way to go, with danger lurking in every shaded area before each pass. The dangers had to be navigated through wisely and tactfully. If it meant turning down television fights that put him at a disadvantage or going months without a fight, Zuhdi was going to go about things his way. Perhaps, it was the right way.

Patience Rewarded

When Zuhdi accepted the fight against the relentless German Jurado for the WBU Lightweight Championship last year, he knew it was the opportunity he had been waiting for. He packed his bags and set up camp in Colorado Springs with trainer Dickie Wood. Zuhdi’s competitive fire spurred him forward to the point, as he said before, that he had done everything he could do. He had done his best. The preparation paid off.

Zuhdi talked about the fight: “I’m always confident. But, at times, I’m too cerebral. I think too much about the variables involved, so I don’t really know how it’s going to go until I get in there. With Jurado and his aggressive style, he didn’t make things any easier. In the last rounds, though, I kind of surprised myself. I still had energy and the fight was slowing down—I could see more. I found out how well I could box. It was a great fight, and its validation is something I needed.”

Witnesses to the action packed fight or the still unreleased documentary of it saw a fighter come into his own that night, a fighter that is still improving at the age of 30. The crowd saw that a middle class warrior does exist and gave him respect with a standing ovation after the unanimous decision victory.

Now, Zuhdi fights for international respect. On the brink of notoriety, he knows fighting a dangerous Vajda in a title defense could lead to bigger and better opportunities. It can provide enough cache to fight evenly matched contenders on national and international television, which is all any boxer wants. It is an exit out of the metaphorical jungle and into a world of respect.

“It’s a bit of new feeling: knowing someone else considers a bout with me to be their most important one of his career. I’m still hungry, too. I want it more than him, no matter how many things are on my plate. I’ll be ready.”

Notes:

The bout takes place on Saturday, August 24, at the Lucky Star Casino (Concho, OK, USA). Tickets are still available at ticketstorm.com

The World Boxing Union is not recognized by the UK but is recognized across Europe and in the Americas. Another one of those things that happens only in boxing.