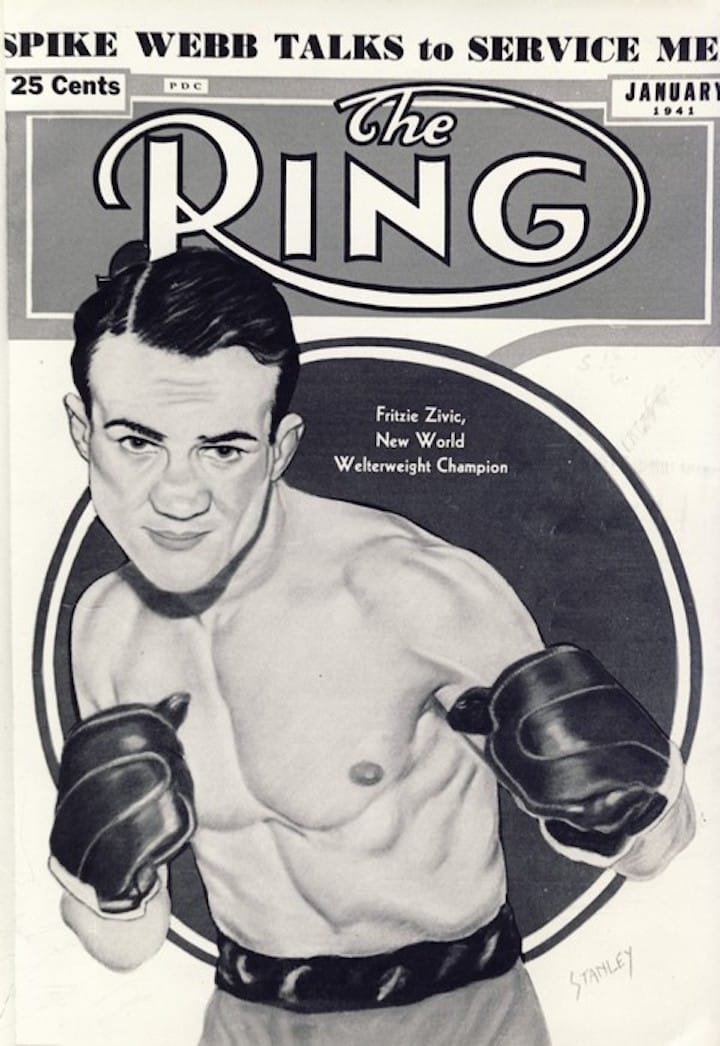

When Fritzie Zivic climbed into the ring at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field on August 29, 1940, he was already a veteran of at least 128 pro fights, and he had been a prizefighter for almost a decade. During that time he had gone from prospect to celebrated journeyman, the sort of veteran that up-and-coming fighters fought to see if they could go to the next level and contenders fought to stay sharp. He won far more than he lost, but his own title hopes were hampered by inconsistency in the ring. He might derail a contender one week and lose to a trial horse the next. But regardless of the outcome, his opponents would leave the ring well-schooled. Zivic was a talented boxer who could control a fight from the outside or slug it out on the inside. He was also known to get as rough as it took, and he nurtured his reputation as a “dirty” fighter because it distracted opponents and sold tickets.

His opponent this night was Sammy Angott, the National Boxing Association lightweight world champion, who, like Zivic, was from the Pittsburgh area. Attending the non-title bout between the popular hometown heroes was boxing promoter Mike Jacobs from New York. Jacobs needed a title challenger for welterweight champ Henry Armstrong at Madison Square Garden in just 36 days, and he believed Angott to be the perfect choice. Angott was a rising star, and crowds loved it when two reigning titleholders squared off.

If the slick-boxing Angott—nicknamed “The Clutch” because of his favorite defensive maneuver—was looking past Zivic on the way to a shot at Armstrong, he was making a grave tactical error. Zivic won eight of the ten rounds, and for good measure scored a knockdown in the sixth. The upset victory raised his career record to 100 wins, 24 losses and five draws. Jacobs was impressed enough by the performance to offer the “Croat Comet” the contract he had originally intended for Angott. But despite his fine showing against the lightweight title holder, few among the boxing experts thought Zivic would be more than a good workout for the mighty Armstrong. As one contemporary scribe assessed, Zivic’s “rise to recognition as welterweight challenger has been steady rather than spectacular.”

Henry Armstrong’s record of 111-13-8 was an indication that Zivic would not have much of an advantage in ring experience. These were a couple of veteran pros in the ring, and on paper they looked well-matched. But Armstrong was world renowned for having held three world titles simultaneously—featherweight, lightweight, welterweight—and he had defended the welter title 18 times going into the Zivic fight. Most thought the 4-1 odds for Armstrong were about right. The title bout promised to be a showdown between a well-seasoned contender and an all-time great.

The fight opened with a flurry of punches as Armstrong demonstrated his patented headfirst, perpetual motion style. Zivic was busy slipping punches, landing body shots, and trying to stay out of the corners. He evaded some of the whirlwind using skilled footwork, but he was too busy fending off the champion to mount an offense of his own. “He hit me from the bottom of my toes to the top of my head,” Zivic recalled. “I thought I was fighting five or six fighters in the first round.”

The second was much of the same, but in the third Armstrong took it up a notch, forcing his way inside, throwing punches, shoulders, elbows—whatever he could land. “He was thumbing me, and choking and butting me. Referee (Art) Donovan didn’t warn him, and I didn’t complain. After all, I was no Little Lord Fauntleroy.” Zivic stayed with him, slipping and countering, but he couldn’t match the champion for volume, and he was reluctant to retaliate with the dirty stuff. “I was afraid that since Armstrong was such a big favorite, if I started to use rough tactics they might throw me out of the ring.”

In the fourth a cut appeared over Armstrong’s left eye, but Zivic’s own eyes were beginning to show the effects of fighting a human buzz saw. In the fifth and sixth rounds, Armstrong continued his all-out assault, throwing a continuous barrage of hooks and elbows. Zivic stayed with him by ripping body shots and landing uppercuts, but as the fight neared the halfway point the champion was clearly dictating the pace and winning the fight. In Zivic’s own assessment, “Up until the sixth I didn’t win a round. I don’t think I won a point.”

As the seventh round began Zivic came out determined to turn the tide, and to him that meant giving Armstrong a taste of his own medicine. Now when the champion hit the challenger in the eye with an elbow, he got a head butt in return. When he thumbed the challenger, he got thumbed back. According to Zivic, at this point Donovan stopped the fighters long enough to say, “Boys, if you want to fight like this, it’s okay by me.” And with those words came a new fight—one in which the Croat Comet would find an advantage. “Finally I started going forward instead of backward as in the first six rounds.” And there were more than fouls coming from Fritzie—he was landing a vicious right uppercut-left hook combination frequently and effectively.

Rounds eight through ten saw the champion begin to wilt under the new attack. His eyes were cut and swollen, and he was reduced to throwing wild punches that Zivic easily avoided and then countered effectively. In the eleventh and twelfth rounds Zivic continued to land power punches without taking much in return. Armstrong’s vision was affected by the pummeling, but the determined champion kept coming forward into the challenger’s attack, absorbing substantial punishment for his courageous effort. The thirteenth and fourteenth saw Zivic further brutalizing Armstrong with an assortment of blows. He would later play up the rough tactics to the delight of his fans: “Every time I butted or thumbed him, being a gentleman, I always said ‘Pardon me.’ In the fourteenth I must have said ‘Pardon me’ at least 69 times.”

As the fifteenth got underway, Zivic looked to finish his opponent, but this meant that for the first time in the bout the challenger was standing flatfooted in front of the champion, and Armstrong was punching back with a renewed ferocity. They stood toe-to-toe and slugged it out in the trenches as the crowd roared its approval. For a few seconds the champion was pushing Zivic back, but it didn’t last. Armstrong exhausted himself, and Zivic came on strong to finish the round. The great champion’s legs were unsteady, and he wobbled around the ring, no longer able to defend himself against the challenger. Just as the round drew to a close, Zivic landed a left hook followed by a right cross and Armstrong fell to the canvas. He was saved by the bell, but the fight was lost. When the judges’ scores were read, Fritzie Zivic was the new welterweight champion of the world.

For his part, Armstrong didn’t dispute the decision. “I lost to Zivic,” he would say in hindsight, adding, “He was just a foul fighter.” He didn’t mention his own alleged transgressions in the bout, but instead laid the real blame for his defeat on the greed of his management. “(Zivic) got me when I was tired and should have been resting but my manager wanted that money.” Considering he had defended his title against Phil Furr just 11 days prior to the Zivic fight, his claim of being ‘tired’ certainly seems legitimate. And he wasn’t getting the best advice going into the bout. “My manager said, ‘You can knock this guy out. He’s easy.

You’ll pick up twenty-five, thirty thousand.’ I got in there and, boy, that was my downfall.”

Armstrong would get another crack at the title barely three months later, again losing to Zivic, this time by twelfth round TKO. He would not challenge for any more titles in his storied career, but he would get a 10-round non-title decision win over Zivic in 1942 for some measure of revenge. “I gave him a good beating. I didn’t try to knock him out. I just wanted to punish him.”

Zivic would lose his crown to Red Cochran in only his second defense, less than a year after his title winning effort. An incredibly active fighter, he fought ten non-title fights during his brief reign as champion. Being an ex-champion raised his stock considerably, but he continued to demonstrate an inconsistency when it came to winning. In one period he rattled off 12 straight victories only to lose 13 of the next 15 bouts. Still, whether his hand was raised in victory or not, he never failed to make an impression on his opponent or the crowd. When it came to prizefighting, Zivic was the genuine article.

Although some boxing insiders considered him past his prime when he first fought Armstrong, after Zivic won the championship he had another 103 fights. During his 18-year career he fought some of the greatest boxers in history, including such luminaries as Sugar Ray Robinson, Charley Burley, Billy Conn, Jake LaMotta, and Beau Jack. He held victories over many of them. He also fought some of the top “club fighters” in a time when being a club fighter was a rough trade rather than a sport and being a journeyman was an honorable profession. Zivic beat some of the best and lost to a few of the lesser talents, yet regardless of outcome he never lacked heart in the ring nor charm outside of it. And regarding his reputation as a dirty fighter, Fritzie was always quick to point out that “you’re fighting. You’re not playing the piano.”