To me, he stands out as the epitome of a heavyweight boxer. Those two words – heavyweight, boxer – those two concepts, balanced equally in his fighting style, each aspect containing the other in equal measure. Nothing in his boxing belied the fact that he was a heavyweight. Nothing in him being heavyweight detracted from his boxing. This runs contrary to the case of great heavyweights in general, of whom many might be said to possess qualities uncommon to men of their weight class – eg. “the agility of a welterweight”, “the hand speed of a middleweight”, the stamina, pace and skills of the lighter men – while others make too obvious their severe lack of those same qualities while possessing in excess those which all heavyweights have over the lighter men ; brawn, brute strength, raw power.

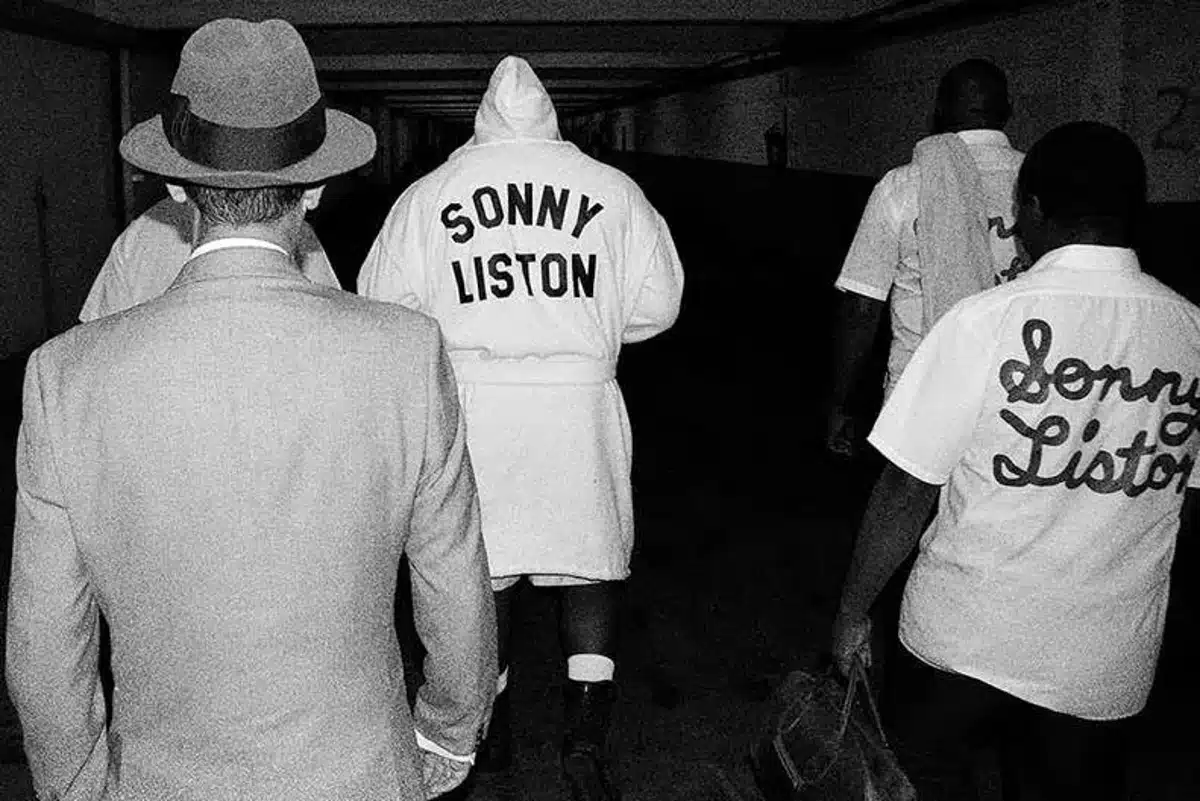

Charles “Sonny” Liston, heavyweight boxer. No other label is more apt. No other label is necessary, save perhaps that simple epitaph upon his grave – “A Man”. Still, it has not stopped him being labelled all manner of things over the years. Thug. Outlaw. Jailbird. Ex-Con. Undesirable. Gangster. Criminal. Those are just a few of the labels, at first put on him out of contempt and fear of where he was from.

Labels designed to alienate him further from the society in which his excellence at his chosen profession should have afforded him some degree of status. Labels designed to further a political agenda. Labels that have now become his ticket into folklore, his guarantee of the lead role – that of the anti-hero – in a pulp crime style tragedy that treads the line between fact and fiction and of which the narrative is incomplete. Reviled and romanticized, Liston remains defined by labels.

Attempting to assess Sonny Liston as a heavyweight boxer also proves problematic. He is by no means the only professional fighter in history to be dogged by the suspicion that he played the key part in a fixed fight. He is probably the only fighter to be suspected of doing so twice in fights for the world’s heavyweight championship though, in front of global TV audiences, and against his most significant rival. Question marks and clouds of confused conjecture continue to hang over him to this day, to such a point where it is possible to voice the opinion that he was both invincible and a coward without looking out of place in the milieu.

No other fighter, to my mind, stands alongside Liston as an alternative perfect example of a heavyweight boxer. Joe Louis was a more perfect boxer ; too perfect a boxer to exemplify a heavyweight. He fought like a heavyweight – in a flat-footed stance and throwing full-bodied punches – but his hands were unnaturally fast and incredibly precise. So too were those of Jack Dempsey, who has long been regarded the epitome of a champion, the mythical hero of boxing’s golden age. When I think of Dempsey at his best, I think of a hungry fighter – too light to make me think heavyweight, too much of a “fighter” to make me think boxer. Muhammad Ali – way too fast for a heavyweight, and unorthodox as a boxer. George Foreman – a bruiser, a puncher, a bomber, a brute, but rarely would you see him box. Larry Holmes ? Yes, Holmes could typify a heavyweight boxer but for more than a hint of Ali-like unorthodoxy in his style.

Sonny Liston had a classic boxing style. And he displayed his style in a heavy-handed manner. He was not slow – in fact he could fire out a jab and an immediate hook off the jab as quickly as any of the great heavyweight fighters – but he did not rely on speed of hand or foot to break his opponents. He did not typically throw lightning fast combinations or rapid-fire triple jabs, turning his fists into a indecipherable blur, as would a Joe Louis or a Muhammad Ali. But Liston’s punches were so heavy, so hard, so heavily-packed with dull thudding heavyweight venom, that it was often evident that being hit by just one of his jabs brought an opponent into new territories of pain and self-doubt. When he put shots together – hooks to the body, his deep looping uppercut, an overhand right hurled from way down field, or his famed left hook – seasoned pros were automatically put into survival mode.

Like any classic boxer, Sonny Liston had defensive skills to complement his attack. Sitting behind that long thunderous jab, his head would be constantly ticking away, up and down and from side to side, the movement controlled by subtle bends in the knees and hips, ready to slip the incoming jabs. When under heavier attack, Liston’s chin would be calmly tucked behind his burly left shoulder, the left arm wrapped across his body, the right arm completely covering his right side – the side furthest from his foe. And in a deep crouch he would be safe enough in his shell to weather the storm and in the perfect position to pounce on his opponent to return fire, which he invariably did.

Some observers have not appreciated Sonny Liston’s boxing style. Far from being seen as the perfect example of a heavyweight boxer, he has been labelled by some as ponderous, stiff, slow and lacking in fluidity. Others have branded him a quitter, a front-running bully, a bruiser with no heart, a brute with no stamina. I do not think these criticisms hold much water. He was not classically graceful or elegant in the ring but he was far from ponderous. He was not slow either, nor was he lacking in stamina, but he could and would dictate the tempo of a fight to suit his own heavy-handed fight plans. He could blast men out with an overwhelming attack or he could torture them on the end of his jab, painfully battering them mercilessly back to the edge of his circle. He picked his punches wonderfully in almost every round of every fight. I suppose others prefer the lumbering big men who hug and coast their way through fights and once in a while pull out a flashy “fluid” combo against a punching-bag type opponent. There is no accounting for taste.

As for him being a quitter, a coward, a fighter with no heart – an accusation thrown at him on account of his surrender of the world’s heavyweight championship to Cassius Clay – I do not buy into such slurs. Sonny Liston fought his way up the rankings the hard way, he was being matched with solid pros and fringe contenders after only 5 pro fights. In his 6th fight he took on tough Detroit prospect Johnny Summerlin, in Detroit. In his 7th fight he returned to Detroit to take on Summerlin again. Both times he earned an eight-round decision. In his 8th fight he faced yet another Detroit fighter in Detroit, the experienced and capable Marty Marshall, who broke his jaw and beat Liston by a hometown split decision. Two fights later Liston was beating the hell out of Marshall, and picking himself up from a flash knockdown to do so. Fighters who are matched as Liston was in his early career do not get far unless they are essentially tough and courageous fighters. It is that simple.

Sonny Liston had the perfect heavyweight physique. Standing between 6’1″ and 6’2″, his arms were extraordinarily long (his wingspan taped at 84″) and the bulk of his 212 pounds was concentrated in his upper body – his thick-set shoulders, arms and neck, his heavily-muscled back. His legs were relatively slight. His hands were huge – it is said his big cannonball fists needed specially-tailored gloves. To any opponent facing him he presented a curious target – a raw mass of fist and shoulder, a cold set of eyes, a scowl – constantly striking from a distance that by rights he should not have been striking from. But few were comfortable with the idea of coming close enough to land their most effectively blows either. While he was not built for classic displays of infighting skill, standing toe-to-toe with him was an invitation for him to take it back to the rules of the alleyway. A surefire way to get whipped.

Sonny Liston once said, “A boxing match is like a cowboy movie. There’s got to be good guys and there’s got to be bad guys. And that’s what people pay for – to see the bad guys get beat.” He was right. And he knew for sure which role he had been cast in. But as he said before facing Floyd Patterson, “ In the films the good guy always wins, but this is one bad guy who ain’t gonna lose”. He tried to change the script. The problem with that is that it is not what the people pay for. No one wanted to see the invincible bad guy destroying all the good guys ; the novelty of that scenario soon wore thin – especially when the good guys were being beat with such ease that they were not even suffering a heroic demise.

Eventually Sonny Liston was forced to go back to the script. Cassius Clay was the new good guy. And while as a young man he may have experimented with the bad guy role himself, Clay – now Muhammad Ali of course – is remembered as the good guy, perhaps the most popular good guy in the history of boxing. And of course it all went beyond boxing.

Sonny Liston was not despised for anything he had done in boxing, he was despised because he represented an American underclass that American society could not face. He made no apologies for where he was from and did not cosy up to the middle-class liberals who expected heavyweight champions to fit their narrow idea of what a role model should be. Nor did he hide his success from redneck America and its racist police. He did not need the endorsement of the NAACP and the black civil rights leaders either – the mere fact that he had survived the bleak deprivation of his childhood should have been enough for those who sang “We Shall Overcome”. He did not believe in non-violence. He was after all a prizefighter. And he hung out with mobsters because in his world they were the only people who had ever advanced his prospects. Frank Sinatra hung out with the mob too ; the difference in America’s attitude towards the two speaks volumes.

In a boxing documentary (The Last Round : Chuvalo vs. Ali), the writer Robert Lipsyte pours scorn on what he describes as a “retrograde romanticism” surrounding Liston. He describes Liston as a “jerk” and a “bully” – safe in the knowledge that Liston has long since passed away of course. Nick Tosches, who penned a Liston “biography” and may well be the arch-romantic, dedicates more space in his book to talking about Liston’s sex organ than he does to Liston’s fights with Cleveland “Big Cat” Williams. Reg Gutteridge, in his autobiography, describes a misunderstood distrustful but fun-loving man ; a man who enjoyed practical jokes, a drink and a wager. Interestingly, it is only Gutteridge among those three who stands out as a solid boxing man. Reg Gutteridge is no phoney.

Having said all that, I do not wish to vouch for Liston’s character or portray him as anything other than a great boxer, a heavyweight boxer. But it appears to me as if people had a problem with him more than he had a problem with people. He once said, “I couldn’t pass judgement on anyone. I haven’t been perfect myself”. I think that sums it up. He will always be remembered as the bad guy. He will always be judged and labelled that way.

In a memorable scene from the film “Scarface” (1983, screenplay Oliver Stone), Al Pacino’s character Tony Montana shouts the following lines at the well-to-do patrons in a posh restaurant :

“You need people like me. You need people like me so you can point your f***ing fingers, and say “that’s the bad guy.” So, what that make you? Good? You’re not good; you just know how to hide. How to lie. Me, I don’t have that problem. Me, I always tell the truth–even when I lie. So say goodnight to the bad guy. Come on; the last time you gonna see a bad guy like this, let me tell you.”

Those thoughts may well have occurred to Charles “Sonny” Liston too.