woulda, coulda, shoulda

An expression of dismissiveness or disappointment concerning a statement, question, explanation, course of action, or occurrence involving hypothetical possibilities, uncertain facts, or missed opportunities. Wiktionary – Wiktionary: Main Page

Ikemefula Charles “Ike” Ibeabuchi (pronounced “Ee-bay-uh-boo-chee”) Ikemefula was born in 1973 in Isouchi, Nigeria, and competed from 1994 to 1999 in the heavyweight division where he finished with a perfect (20-0-0, 15 KOs) record. If there was any heavyweight with the skill and power to become the dominant heavyweight in his era, it was Ibeabuchi—had he possessed the concomitant mental strength to fulfill that promise.

As a teenager, ready to enlist in the Nigerian military, Ibeabuchi watched the infamous James “Buster” vs. “Iron” Mike Tyson bout in Tokyo back in 1990. James “Buster” Douglas entered the ring a 42-1 underdog for the fight; Tyson was in his prime, the undisputed heavyweight champion who defeated most opponents from sheer panic before they even entered the arena. Inspired by Douglas’ stunning upset of Tyson, Ibeabuchi entered the amateur ranks. After defeating his fellow Nigerian-born opponent Duncan Dokiwari, a 1996 Olympic Bronze medalist, Ibeabuchi moved to Texas and eventually won the State Golden Gloves tournaments at heavyweight in 1994.

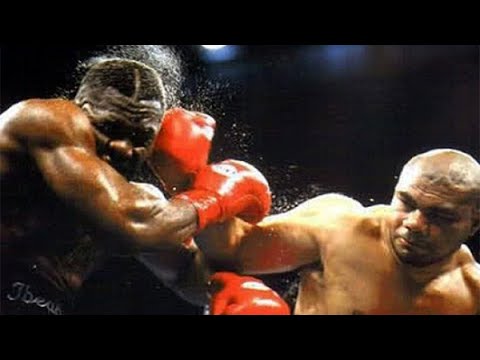

In 1997, the undefeated Ibeabuchi fought the heavy-handed knockout artist David “Tuaman” Tua for the WBC International Heavyweight belt. Tua, born in Samoa (later moving to New Zealand), was 27-0 and widely thought to be the second coming of Mike Tyson because of massive strength and frightening knockout power. The fight surpassed all expectations and put Ike on the map as a potential superstar. Both boxers hurled massive, incendiary bombs with each fighter walking right through the punches. In only his seventeenth professional fight, Ibeabuchi outlasted the Tuaman over twelve rounds for the victory and withstood enough of Tua’s legendary left hooks to drop an elephant. The fighters set a CompuStat heavyweight division record with 1,730 punches thrown (at that time), setting up Ibeabuchi as top contender for the world heavyweight title.

It was then that the genuine trouble began. Clinically insane behavior.

Irked after a low WBC ranking following the Tua fight, Ibeabuchi decided to kidnap his ex-girlfriend’s 15-year-old son and drive his car into a concrete pillar in Texas. The boy suffered heinous injuries, and Ibeabuchi was charged with kidnapping and attempted murder. The Court concluded Ike was attempting to commit suicide, and he was sentenced to 120 days in jail after pleading guilty to false imprisonment and subsequently paid a $500,000 civil settlement.

But being a rising star in boxing can give you lots of breaks in the real world. Even when you display obvious signs of sociopathic behavior.

Ike Ibeabuchi’s boxing nickname was “The President,” and Ike cultivated an identity based on his moniker. When asked to perform such basic requirements—e.g., participating in weigh-ins or attending meetings with promoters—The President often scoffed, considering such acts beneath a man of his stature. It got to the point where his team would convince Ike to engage by persuading him that, being of royal nature, it was the only magnanimous way to proceed.

According to Ike’s former boxing promoter and HBO sports executive, Lou DiBella, “[t]here were times when he thought he was really a president. He would get into these mental states where he insisted on people calling him ‘The President.’ It was his alter ego, where ‘I am The President,’ not of the United States, but maybe president of the world.”

Other examples of Ike’s regality:

· Ibeabuchi brandishing a knife during a dinner meeting in New York regarding a three-fight HBO deal. According to his former promoter, “[w]e were having a fine meal at a nice restaurant, and mid-course Ike picked up a big carving knife, slammed it into the table and screamed ‘They knew it! They knew it! The belts belong to me! Why don’t they just give them back?’ [He] was like a Viking.”

· Refusing to get into the ring to fight unless he had a Snickers bar and forcing an entourage member to scurry to a store close by to obtain the candy. A former promoter once mused, “Do [we] really want to be on ESPN one day as the promoter of the world heavyweight champion who murdered somebody? Because this guy is very capable of doing that. This guy’s crazy. He’s […] he’s quite capable of killing somebody.”

· Nearly refusing to fight while waiting in his hotel room because of perceived malevolent spirits flowing through the building. DiBella recalled, “Ibeabuchi’s mother was staying at the hotel with him, she said, ‘Ike’s not going to fight, there are evil spirits in the hotel. And they’re coming in through the air conditioning system.’” So, another promoter did the only logical thing by saying, “Ma’am, turn off the air conditioning.”

Despite all the craziness, it appeared that Ibeabuchi was poised to take over the heavyweight division. Six foot two and 240 lbs. of mesomorph’s muscle, the Nigerian-born slugger, had all the tools: colossal power, an igneous chin, and intelligence in the ring. So strong he once knocked a heavy bag off the wall, after hitting it so hard the whole frame came off.

After the Tua victory, Ibeabuchi returned to the ring and won his next two fights, which set up a bout against 1992 Olympic silver medalist/future heavyweight champion Chris Byrd in 1999. Byrd was a talented, clever, and slippery southpaw with a record of 26–0-0. In this bout, Ibeabuchi wielded magnificent ring smarts by demonstrating an ability to dissect his opponent’s style and adjust his own accordingly. Aside from Wladimir Klitschko, no one has dropped Chris Byrd in such a cold, powerful way. Ibeabuchi bided his time, putting pressure on Byrd, trying to get his hands apart and looking for a hole in his defense. Byrd himself recalled:

Most heavyweights don’t have a lot of boxing sense. […] But he was different, where he would come, and he would just use his knees, get up under, try to get low, and pick his shots […], and [s]o, he’s gunning more for my shoulders knowing how I’m dipping and how I’m moving, I’m eventually going to get caught on the chin. Because where my hands were, and how I was moving. I was actually having a lot of fun. Until I got hit with that — it looked like it was an uppercut, but he turned it into a hook or something, boom, I walked right into it. When I got knocked down the first time, I got, literally, the canvas woke me up. I was asleep before I hit the ground, and when I hit the canvas, it woke me up. I didn’t go to sleep, I got back up. I still fought. And it was a bad — I mean, slobber came out of my mouth, I fell flat on my face. But my will to win. And then, go down, get back up, go down again, get back up, but then I complained to the referee, like, Why you stop the fight? It hit the five second before the round, five or 10 seconds, and I’m walking back to the corner, and Ike kept throwing at me. I thought it was the bell. So I’m like, oh my goodness, and he stopped the fight, I’m like, What are you doing? Why you stopping the fight? The bell rung! But I had my bell was still ringing, that’s what was ringing was that bell.

Ibeabuchi had landed a vicious uppercut that lifted Byrd up off his feet and had him literally drooling on the canvas, staggering and foaming around the canvas. After the fight, Ike said, “I’m ready now, I’m ready for the world heavyweight championship.” Ibeabuchi absolutely looked like a boxer that would rule the division and obliterate those other guys (e.g., Lennox Lewis and Evander Holyfield) that dare block his Majesty’s path. Even Ring magazine anointed Ibeabuchi “boxing’s most dangerous man.”

But Ibeabuchi’s demons finally caught up with him before he had a chance to become Baddest Man On The Planet.

It all came crashing down for Ike in 1999 at the Mirage Hotel in Las Vegas after he held a stripper captive and beat her after a dispute over, er, proper payment. Ibeabuchi barricaded himself in the bathroom and the cops had to discharge pepper spray under the door to get him to surrender. Ibeabuchi faced quite the legal pickle at this juncture, as the Clark County District Attorney’s office reopened a similar sexual assault allegation that took place eight months prior at the Treasure Island Hotel and Casino

The Court found Ibeabuchi incompetent to stand trial and was sent to a state facility, where medical experts diagnosed The President with bipolar disorder, and a judge granted permission to force-medicate him. Ibeabuchi subsequently entered an “Alford” plea (pleading guilty while not admitting guilt to avoid going to trial) and was sentenced to two to ten years for battery with intent to commit a crime and three to twenty years for attempted sexual assault.

After years of incarceration and wrangling with the criminal justice system and the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to resolve his immigration and United States citizenship status, in April 2016, Ibeabuchi was arrested for violating the conditions of his probation in Arizona based on an old warrant dating back to 2003 of which he was unaware. Ibeabuchi will complete supervision on April 25, 2020, at which time he will be 47 years old.

Throughout the history of the planet—whether in the arts, athletics, or academia—there have been countless human beings teetering on the edge of sanity that achieved moments of true genius. Some opine that a fine line exists between insanity and brilliance. Ike “The President” Ibeabuchi surely fits in this opaque arena.

jakeameyers@gmail.com