01.06.07 – By Mike Dunn: Did Sonny Liston throw one or both of his fights with Cassius Clay? A lot of people think so, including boxing insiders. Many others don’t believe it. Some think Liston may have thrown the second fight in Lewiston, Maine, but not the first one. In any case, controversy has been a shadow over the two Clay-Liston fights and that shadow remains to this day. Unsatisfactory endings to both bouts (in February of 1964 at Miami Beach and in May of 1965 at Lewiston) have created speculation and cast doubts about the veracity of Liston’s performances.

01.06.07 – By Mike Dunn: Did Sonny Liston throw one or both of his fights with Cassius Clay? A lot of people think so, including boxing insiders. Many others don’t believe it. Some think Liston may have thrown the second fight in Lewiston, Maine, but not the first one. In any case, controversy has been a shadow over the two Clay-Liston fights and that shadow remains to this day. Unsatisfactory endings to both bouts (in February of 1964 at Miami Beach and in May of 1965 at Lewiston) have created speculation and cast doubts about the veracity of Liston’s performances.

In simple terms, this is what happened in the two encounters: Liston lost his title to Clay (who would soon change his name to Muhammad Ali) in the Miami Beach bout when Liston refused to come out of his corner for the seventh round. Liston, who had received a thrashing at the hands of the younger, quicker Clay, claimed that his left shoulder had been injured.

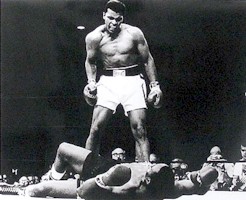

In the rematch a year and three months later, Liston went down in the first round from what some referred to as a “phantom punch.” It appeared that Liston was able to get up, but chose not to. Clay (now known as Ali) was awarded a first-round KO.

Did Liston throw either fight or both?

Those who believe Liston laid down typically point to his mob connections. In 1964 and 1965, Liston was under the influence of a flamboyant character with underworld ties named Ashe Resnick. Resnick owned a Las Vegas casino called the Thunderbird, where Liston trained. It is a fact that the Thunderbird was controlled by the New York mob. It is also a fact that Resnick and Liston had a close relationship.

There’s no disputing that when Liston went into the ring both times against Clay, Resnick was very much a driving force in Liston’s life. Did Resnick orchestrate a gambling coup by prearranging for Liston to lose in the middle rounds in the first fight? Did Resnick prearrange with Liston to go down in the first round of the rematch?

While it’s easy to leap to conclusions, there’s no evidence at all to support the fixed-fight theory.

The hard facts are these: 1. Liston was much more valuable to Resnick and to the mob as the champ than as the ex-champ;

2. The mob had no ties with Clay/Ali, and therefore it was not to the mob’s advantage to have Clay/Ali as champ; 3. There has never been a verifiable paper trail, testimony trail or money trail that has proven there was a fix in either fight.

If Liston wasn’t part of a fix, then what happened?

When Liston put his title on the line against Clay (who would later become known as Muhammad Ali) on Feb. 25, 1964 in the Miami Beach Auditorium, Liston was thought to be invincible. Liston, whose intimidating presence and predatory scowl evoked fear in the strongest of men, walked into the ring that night as an 8-1 favorite. No one had any idea before February of 1964 what Clay/Ali was going to become. Clay, the brash, young challenger from Louisville, Ky., had just 19 pro fights to that point and frankly wasn’t considered much of a threat to Liston’s crown. In Clay’s previous two fights, he had earned a narrow 10-round decision over a much lighter Doug Jones in a surprisngly tough battle at Madison Square Garden, and he had been on the deck in the fourth round and in some difficulty against England’s Henry Cooper before registering a fifth-round KO. Clay was undefeated, true, but he hardly had what one would call a glittering resumé.

Liston, by contrast, had a record of 35-1 and was being compared favorably to the greatest of heavyweight champs, including Joe Louis. Liston was the recipient of the same kind of “Superman” hype that, in later years, George Foreman and Mike Tyson would be subject to.

The public by and large believed that Clay would succumb to Liston’s heavy fists in the same manner that Floyd Patterson and Cleveland Williams and Albert Westphal and Zora Folley had. More importantly, Liston believed it, and that was the champ’s undoing.

It’s common knowledge that Liston didn’t train very hard for the Clay fight. Some boxing insiders, including writers Nigel Collins and Jerry Izenberg, partially blame Resnick for Liston’s lack of conditioning. They say that Resnick fed Liston’s appetite for wine, women and song and, even worse, had Liston believing his own press clippings, which is always dangerous for a prizefighter.

The result was that Liston went into the ring at Miami Beach unprepared to go 15 hard rounds with Clay. As it turned out, Liston couldn’t go six hard rounds with the younger, faster challenger.

Did Liston’s corner ‘burn the gloves’?

Clay turned out to be bigger and stronger than Liston expected. And Clay didn’t melt when Liston stared at him. Those factors no doubt worked against the champ.

When it became apparent to Liston that he wasn’t going to beat Clay the conventional way, he allegedly ordered one of his cornermen to “burn the gloves.” According to reliable sources, an ointment was then rubbed on Liston’s gloves prior to the start of the fourth round and Liston employed chemical warfare tactics to try and balance the scales. The illegal strategy may have worked, except for Clay’s ability to take a hard beating to the body and the presence of mind of Clay’s trainer Angelo Dundee.

Clay came to his corner after the fourth round complaining of a burning sensation in both eyes. It’s obvious from film footage that Clay was in a lot of discomfort. Clay told Dundee to remove his gloves and stop the fight, but Dundee remained calm and helped Clay to ride out the storm. “This is for the world championship,” Dundee told his fighter. “There’s no turning back

now.” When the bell rang to start the fifth round, Dundee told Clay to retreat and pushed him out to meet the champ.

As the film clearly shows, Liston did his best to get to Clay during the first two minutes of the fifth round. If Liston and Resnick had prearranged for Liston to lose, then why was Liston trying so frantically to get Clay out of there?

In fact, Liston landed several hard blows to Clay’s midsection during those two minutes. Clay, as he would prove many times later in his career, could take a whale of a punch. Liston landed to the body but wasn’t able to connect solidly to Clay’s head, as Clay instinctively moved back and held on. Clay may have been blinded, but he was still elusive. After two minutes, Clay’s perspiration began to wash the sting of the ointment from his eyes and he was able to see clearly again.

From then on, Clay administered a healthy beating to the once-fearsome champ. It appeared a few times that Clay might even knock Liston out. Liston, an angry welt raised under his left eye, sat on his stool and refused to come out for the start of the seventh round. He was an exhausted and thoroughly beaten fighter. As Dundee and others have noted since, “Liston got old during the fight.” He went into the ring as the most feared pugilist in the world and he left the ring in humiliation. The story about the injured left shoulder was apparently an excuse concocted to soften the blow of Liston quitting in his corner.

Why didn’t Liston get up at Lewiston?

Fifteen months later, the fighters faced each other again, this time in a converted high-school hockey rink in Lewiston, Maine. Incredibly, Liston went into the ring that night as the betting favorite again.

People like myself who don’t believe that the fix was in at Lewiston are hard-pressed to explain Liston’s actions. Liston looked for all the world like a fighter cashing in the chips that infamous night. He almost certainly could have gotten up, but he chose not to.

If the fix wasn’t in, then why didn’t Liston get up?

There isn’t a simple answer to that question. There are several factors that play a role in the controversy that surrounds Clay-Liston II. Here are three of those factors:

1. Clay’s hernia < The rematch was originally scheduled to be held in Boston in November of 1964. Liston, perhaps ashamed of what happened in Miami, started to dedicate himself to training once more. In the weeks leading up to the scheduled rematch, he got himself into what he told the media was thebest shape of his life. Many believe that if the Clay-Liston rematch would have taken place in Boston as scheduled, Liston would have given the new champ all that Clay could have handled.

Alas, Clay sustained a hernia and had to be rushed to the hospital. The fight was postponed for six months. As author David Remnick points out his excellent 1999 book, “King of the World,” the sudden postponement took all the steam out of Liston. He discontinued the training regimen for a period of time and, when he resumed again, was never able to make up the lost ground. He would never get back into that same kind of physical condition again. The combination of age and high living were taking a heavy toll on Sonny Liston.

2. Malcolm X assassination < In February of 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated in New York city. Clay, who had publicly embraced the Muslim faith by that time and had officially changed his name to Muhammad Ali, had been very close friends with Malcolm X in the early 1960s. Clay/Ali later disassociated himself with Malcolm at the behest of Elijah Muhammad, the ruler of the Muslim sect to which Clay/Ali belonged. When Malcolm was subsequently assassinated in New York by Muslims of a rival sect, there were rumors that an assassination attempt was being planned against Clay/Ali in retaliation.

In the aftermath of the Malcolm X assassination and the revelation that Clay himelf was now a possible target of assassins, the Clay-Liston rematch “had a stink about it,” as Izenberg phrased it. Nobody wanted the fight. Finally, the blue-collar city of Lewiston offered to stage the bout. The offer was quickly accepted.

The fight now had a venue, but there was still an atmosphere of tension and foreboding surrounding the whole promotion in the days and weeks leading up to the rematch. On the day of the fight, everybody entering the small arena were searched for weapons. A few days before the fight, a contingent of Muslims went over to Liston’s camp and met with the former champ. No one knows what happened or what was said at the meeting. Many believe that Liston received threats of some nature.

In any case, the assassination scare was taking its toll on everyone, including Liston.

3. Listons’ mental state < Here is a man who had taken a pounding at the fists of the younger, faster Clay 15 months before. Liston is older and slower now, feeling the impact of age. His reputation as Superman is shattered. He's getting knocked around by his sparring partners, something that has never happened to him before. Things have gotten so bad, in fact, that Liston's handlers have secretly asked the sparring partners to take it easy on Sonny. Clay, meanwhile, is maturing into his body. He's at his physical peak now and has the great inner confidence that comes with winning the world championship.

Going into the ring on the night of May 25, 1965, all of these things had to have been preying upon Liston’s mind. He hadn’t been able to get into the kind of shape he wanted to. Would Clay knock him out this time? Would he be humiliated? Sonny remembered the beating that he took at Clay’s hands the year before. Did he really want to go through that again?

Liston WAS hit by a solid punch

The bell rings. Liston comes out tentatively, throwing ponderous jabs toward the head of Clay and rights to the body. Liston pursues. Clay retreats. Suddenly, Liston is down. It is later revealed that a short, chopping right hand counter by Clay catches Liston squarely. The films reveal that there is definitely a punch that lands, though many suspect that the blow isn’t hard enough to send the former champ to the canvas.

Clay waves for Liston to get up. Referee Jersey Joe Walcott doesn’t pick up the count from the timekeeper because Clay is running wildly around the ring. As Walcott goes to confer with the timekeeper, Liston gets partway up. And then he falls back down again.

There is chaos in the ring as Clay keeps circling and jumping up and down. After 13 seconds or so have elapsed, Liston is finally on his feet. It appears at first as if the fight is going to resume. But no. Walcott is now being summoned to ringside, this time by magazine editor Nat Fleischer, who tells the ref that the timekeeper had reached 10 seconds with Liston on the canvas.

Walcott rushes back over to the other side of the ring, where Clay is throwing punches and Liston is in a defensive shell. Walcott breaks the fighters apart and raises Clay’s hands. It’s over.

Looking for a soft place to land?

Clay later tells reporters that he heard the word “fix” being yelled from the spectators as soon as Liston went down. Clay waved to Liston to get back up, but to no avail. Clay would explain that the knockout blow is the so-called “anchor punch” that Jack Johnson used to employ. It’s all rhetoric, though. Right after the fight, Clay told cornerman Abdul Rahman that Liston had taken a dive.

What seems clear about the whole sordid affair is this: Liston was indeed hit by a punch; Liston went down; Liston could have gotten up but chose not to.

Was it a fix? Liston never admitted to it. His widow, Geraldine, says to this day that if it was a fix, it was a secret that Sonny took to the grave with him. And if it was a fix, Geraldine says, there was never any kind of financial payoff.

What is more likely is that Liston was looking for a soft place to land. Maybe he took the threat of the Muslims seriously. Maybe he didn’t want to be in the ring too long that night, in case somebody had a gun and started firing. Or maybe he just didn’t want to get beat up again.

Liston’s behavior is not unprecedented. It mirrors that of Jersey Joe Walcott in Walcott’s title rematch with Rocky Marciano. Walcott and Marciano had engaged in one of the great heavyweight fights of the ages in September of 1952, with Rocky finally winning in dramatic fashion with one short, powerful right-hand blow in the 13th round. The rematch proved to be a dud, though. Walcott absorbed one grazing blow from Rocky, a right uppercut, and went down near the ropes. He waited for the ref to count 10 and then he got up.

Walcott, like Liston, was feeling the effects of age and Walcott, like Liston, had endured a physical pounding from a young, tough challenger while losing the title.

Liston followed in Walcott’s footsteps. The problem is that Sonny did as poor a job of portraying a pugilist in trouble that fateful night as Robert Goulet did of singing the national anthem. Goulet forgot the words. Liston forgot not to duck.

And so the controversy continues to this day.

* Information for this article was gleaned from several sources. The main sources were “The King of the World,” by David Remnick; “The Devil and Sonny Liston,” by Nick Tosches; a video of the HBO special entitled “Sonny Liston: The mysterious life and death of a champion”; a video entitled “Muhammad Ali, the Whole Story”; and a video entitled, “When Clay Shocked the World.”

Mike Dunn is a boxing historian and writer living in Lake City, Mich.