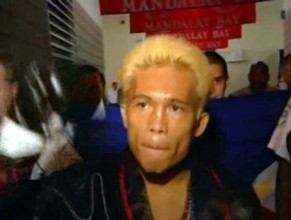

(Czar Amonsot, in photo, before his bout with Michael Katsidis) 18.08.07 – By Gabriel DeCrease: Perhaps it is the hangover of the De La Hoya/Mayweather fiasco lingering, that sense that the trend in boxing coverage is leaning ever-closer to the bonfire of international celebrity. As boxing has, over the last decades, been supported more by its cult of devotees and less by the revolving door of casual observance, a greater number of fighters have been celebrated–and celebrated for their skill or old school determination instead of their ability to appear wholesome, eloquent, or dashing giving a thumbs up on a cereal box.

(Czar Amonsot, in photo, before his bout with Michael Katsidis) 18.08.07 – By Gabriel DeCrease: Perhaps it is the hangover of the De La Hoya/Mayweather fiasco lingering, that sense that the trend in boxing coverage is leaning ever-closer to the bonfire of international celebrity. As boxing has, over the last decades, been supported more by its cult of devotees and less by the revolving door of casual observance, a greater number of fighters have been celebrated–and celebrated for their skill or old school determination instead of their ability to appear wholesome, eloquent, or dashing giving a thumbs up on a cereal box.

I think that the decline in mainstream interest in boxing has provided a rare-moment in sport when a generally knowledgeable fan-base can elevate fighters like Bernard Hopkins, Winky Wright and, to a lesser degree, Carlos Baldomir to a place of distinction for specific achievements that have little to do with cross-over appeal.

That said, the fight that was to save boxing, appears to have had some decidedly opposite impact as it has people wondering how to lure the mainstream back to the sport. If those same folks made a list of things to avoid putting on the front lines of that sales strategy, traumatic brain-injury and the sudden ends to the careers of a brawling Mexican warhorse who crawled jab-over-cross out of poverty and through deep rounds with some of boxing’s best in the lower weight classes, and a I am referring, as you may-or-may-not be aware, to the career-ending brain-injuries that both Oscar Larios and Czar Amonsot sustained in their fights against Jorge Linares and Michael Katsidis, respectively.

I say that you might not be aware of these happenings because they got so very little press, and only a few mentions of the injuries ran in the also-noted section–back-page corner–of some dailies. The boxing press in-general was eminently interested in nominating Katsidis as god of 135-pound thunder-and-lightning. And why not? Katsidis is a sledgehammer-punching tornado (albeit a somewhat slow, defense-eschewing, and beatable one) with clean-cut good looks that cry out for endorsements in advance of a legitimized title-reign. If, after the 12-round pounding he doled out to poor Amonsot, much was made of the potentially life-threatening brain injury the Filipino challenger sustained, some of the luster might have been drained from the champion’s prolonged victory parade, which has been carried onward past the now-recovering Amonsot and toward his next fight.

With Katsidis’ management looking toward match-ups like the once-scrapped scrap with Joan Guzman, now back on the table after this latest victory, any lament for Czar Amonsot would be a detraction that is beyond redemption. Amonsot will never fight again, I hope, and certainly not with any great fanfare. And to linger on such a cold fact would be to remind us all of the fact that boxing is, by its nature, very dangerous–even for the strong, and especially for the brave. Boxing purists, the cult that held sway in the absence of mainstream coverage, most-often squared themselves with that fact, and went on to view the sport with that knowledge integrated into their interest and reverence.

There has been a shift, somewhat invisibly, across the beats of boxing reporters, toward avoidance of the sometimes-bloody and permanent dangers of the fight. And to this end, fighters who went out on their shields, as it were, are being denied the memorial shells that ought to be fired after the fall.

Diego Corrales was heavily memorialized and eulogized across even mainstream sports news outlets because despite the fact that most of his fights could have (and, in many cases ought to have) killed him, he died in a motorcycle wreck. There is a media friendly rub somewhere in there that allows for the mention of his face-first, all-out fighting style to end with his end coming from another angle that cannot fuel the familiar verbiage of boxing-abolitionists.

(Oscar Larios, seen here after being knocked down in the 10th round by Jorge Linares on July 21, 2007) So now, with that off my chest, I want to offer some late tributes to the late, great Oscar Larios, and to Czar Amonsot, who, in all honesty, was no world-beater, but who earned this notation by standing-tall to make the sacrifice that looms as a constant-potentiality above the worn brows of fighters at every level. I believe this sacrifice is not one that need be downplayed or spun. It is simply the truth of a game in which the object is to knock your opponent unconscious or otherwise beat them into submission.

(Oscar Larios, seen here after being knocked down in the 10th round by Jorge Linares on July 21, 2007) So now, with that off my chest, I want to offer some late tributes to the late, great Oscar Larios, and to Czar Amonsot, who, in all honesty, was no world-beater, but who earned this notation by standing-tall to make the sacrifice that looms as a constant-potentiality above the worn brows of fighters at every level. I believe this sacrifice is not one that need be downplayed or spun. It is simply the truth of a game in which the object is to knock your opponent unconscious or otherwise beat them into submission.

Czar Amonsot was, after an initial MRI indicated bleeding on the surface of the brain, told by emergency room doctors he would never fight again. Then, just weeks later, other physicians went so far as to say the fortuitous placement of the injury and the emergent care he received in the crucial hours after the fight put Amonsot on the road to a recovery that could be complete enough to put him back in training within the year. That type of talk always does, and should, shake me to my core. Such an injury, even if the single-instance is not permanently-damaging, demonstrates a physical vulnerability that one ought not to carry onto terra so dangerous as the prize ring. Fortunately, subsequent examinations have put a greater distance between Amonsot and a comeback (or the ability to be cleared, sanctioned, or given a license to fight). So, in paying tribute to his mortal sacrifice, I am toasting the hope the Amonsot’s career will have ended with a hard-fought last stand against a ferocious young champion. If Amonsot is permitted to resume his career it will be, I think, in error. It was not until his injury that I made the effort to track down grainy videos of his fights. He was tough, quick, intense, and sometimes on-fire with the very rage that was his undoing as it crippled him stylistically against Katsidis. In Amonsot’s own words, There’s no excuse. I lost because of me. I failed to control my temper.” Here’s hoping that fury and bloody passion will not stop him from heeding the terrible warning he received in the form of a traumatic injury.

Oscar Larios was born into hard-luck. He was the product of working-class poverty in Zapopec, Jalisco, Mexico. His life before entering the prize-ring was one in which he earned everything he had (and, by that necessity, defended it vehemently). Once he began his professional career at seventeen, he continued that trend without hesitation or fear. He rattled off a string of early victories, always busy, determined, and serious in the ring. Early, brutal knockout-losses to then up-and-coming Israel Vasquez and rugged, iron-hide veteran Agapito Sanchez that might have made many fighters think seriously about the toils of pugilism only spurred Larios, nicknamed “Chololo,” onward with greater determination. In one of his finest performances, Larios rallied after a mauling back-and-forth to stop Vasquez in the final stanza of a subsequent rematch. That very grit saw him through a super-bantamweight title-reign that included thirteen defenses of the WBC alphabet-strap between, ironically enough, his second and third fights with Vasquez.

His early loss to Vasquez in 1997 (Vasquez was, at the time, 11-1-0) was, maybe, an early indication that Larios would not rise to the top of the talent-pool. Everything he was, he worked for, he was not naturally phenomenal, not so heavy-handed, not blindingly-quick, not precise in his movements. But courage goes a long way when one is dealing in blood, leather, and canvas. His rematch victory over Vasquz showed just that. And, perhaps, that point was made even more firmly as Larios was flattened in the 2005 rubber-match. By then, Vasquez had become an elite fighter, something Larios did not have in him. But “Chololo” went all the way. Before Vasquez fought Rafael Marquez he said he would die in the ring if it was a choice between death and quitting, as it so often is in this perilous sport. Vasquez went on to suffer a broken nose and quit on his stool because his busted-beak was inhibiting his breathing. Vasquez lived to win the rematch. Oscar Larios had to be knocked senseless, and usually came up wishing he had beat the count. For that he earned a subdural hematoma, and the kind of respect for which there is qualitative evaluation. He hung tough with Manny Pacqiuao, and when he realized his opponent was quicker and stronger, he screwed his resolve down and took the mugging the distance, fighting back when he could, taking two (or eight) to land one. My kind of guy.

His title reign was real. His record was blemished early, and late, but there was a moment when his courage prevailed (notably during his pair of great fights with an equally determined and gutsy Wayne McCullough). It included none of the fight-dodging shenanigans that make us question the lesser champions that get needlessly and undeservingly stirred into the oft-rancid alphabet stew. Oscar Larios deserves to be remembered as a fighter who in iconic portraits of bloody-realism brought the best and most-admirable–and perhaps indomitable–aspects of boxing to fulfillment. I use the term indomitable because it is to say a man was beatable, or able to lose, but that those losses did never defeat him. Not even in being retired by the concussion, literal and metaphoric, of all those hard, deep fights, is “Chololo”” conquered, or is his courage questionable.

Author’’s note: At the time of his fateful meeting with Jorge Linares, Oscar Larios was under the promotional care of Oscar De La Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions. The Golden Boy, it seems, sometimes puts profound purity of pugilism over profits in his considerations of whom to represent. For that, I will forgive him the refund he owes me for the bore-fest with Mayweather that distracted, and did not save, boxing, after all.