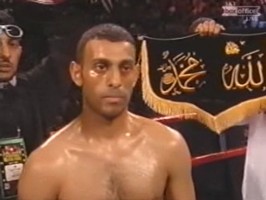

21.08.07 – By Andy Olsen: This two part article is on fallen champion Prince Naseem Hamed. It aims to provide a bit more of a balanced aspect to his career than the ones which have recently surfaced. Of course, the old saying in boxing, “the last look is the lasting look” has a certain amount of truth to it; it’s why his career is viewed in the way it currently is.

21.08.07 – By Andy Olsen: This two part article is on fallen champion Prince Naseem Hamed. It aims to provide a bit more of a balanced aspect to his career than the ones which have recently surfaced. Of course, the old saying in boxing, “the last look is the lasting look” has a certain amount of truth to it; it’s why his career is viewed in the way it currently is.

Hamed lost his way, was exposed by a true great, and limped out of the game with a truly dire performance. Adding to this his jail term for his act of sheer idiocy behind a steering wheel, and it makes said commentary of his career understandable, to say the least. But it is these facts which cloud over how meteoric his rise was.

I myself needed TV channel ESPN classic to show his first few fights to remember this, and contemplate just what a career this guy actually had in his prime. My appreciation of easy to follow logic leads me to cover this in the first part of the article. The second will add further commentary as to his downfall, and try and cover the numerous reasons why the “legend soon to be” didn’t end up as such.

You all know the route prospects take. Rack up the wins and learn the trade, whilst staying undefeated throughout. Acid tests come along, and it is here where they get judged for sure. Sometimes however, certain boxers come along and show seasoned observers something they’ve never seen before. And they get the attention of the trade quickly. Hamed was such a case. His performances were almost spellbinding, even taking into account his modest opposition. Ricky Beard was considered to be a hard opening test, yet two rounds was all it took for the Hamed camp to prove otherwise. 0-11 Andrew Bloomer was almost a stone (12 pounds) heavier, yet spent the entire contest (3 rounds) with his hands by his head trying to work out just what on earth this guy was going to do next. Believe me, he certainly wouldn’t be the last of Hamed’s 37 opponents to be in such a predicament.

Despite being thoroughly entertained, the crowd loved it when he missed with wild lunges etc. It all made him even more watchable, if not liked. And the vulnerability, which he brought himself on with outlandish moves, previous reserved for the local nightclub, would catch up with him, but at a much later time. At this point in time, his Unbelievable speed and reflexes (Promoter Frank Warren still maintains Hamed is the most naturally talented fighter he’s ever worked with) would allow him to get out of trouble, should such a move not pay off.

Hamed’s “acid test” was brought on much earlier than the typical prospect I was referring to before. In his twelfth contest, he was put in with solid and respected European Bantamweight champion Vincenzo Belcastro in May 1994. Hamed put on the first of many a punch-perfect display that night. He put the Italian down twice en route to a shutout points victory, in what was supposed to be a fight which had come far too early for him.

Out of interest, I pointed out in my recent preview of Amir Khan’s last contest (the undefeated Bolton Lightweight, who has enjoyed a similar amount of hype as Hamed), that he took on a 24-4 Trailhorse in his twelfth contest, a three round blast out. Khan is clearly a work in progress, with a great deal to be worked on in certain aspects. Compare this to Hamed’s contest with Belcastro, and it should further serve as proof of what an amazing natural talent this guy was.

A few fights later, and Hamed became a main-event Sky TV attraction. The fights (in which Hamed would defend his WBC international super-Bantamweight title) served purely to showcase his talent. They served their purpose. Add to this WWE style ring entrances, complete with pyrotechnics and the latest club cuts, and a new demographic of audience had found a fighter in which they could identify.

Of course, such would alienate another audience from being fans of Hamed. He had an array of detractors within the British fight game, who disapproved of such antics, both in the build up, and in the ring itself. It sounded outlandish at the time, but certain experts claimed Hamed lacked in fundamental skills, with his speed, balance, and reflexes covering said flaws up. It would be several years before people came to see that they had a point.

Hamed was 21 years old when he fought Welshman Steve Robinson for his WBO Featherweight title. However it was a contest where he had to show maturity far beyond his years. It wasn’t just down to the accomplished opponent, who rose from journeyman status to win the title at 24 hours notice. Hamed was the slight favourite, yet in order to win the title he had to win it in Wales at the old Cardiff Arms Park. The crowd there had no interest in seeing him do this, and it was one of the most hostile atmospheres imaginable.

The chant of “Hamed, Hamed, who the f##k is Hamed”, which resounded throughout the stadium during the undercard and wait for the main event was one of the more pleasant ones. During his ring entrance, Hamed later claimed he was spat at, and suffered racial taunts from certain elements of those in attendance, the majority of whom thankfully have seemed to vanish from British sport. Looking back, it made the performance even more special. Most would have been perturbed and intimidated by such, yet Naseem responded by not giving Robinson as much as a look-in. Light years ahead in terms of speed, he taunted his foe throughout, making him look amateurish at times. He put Robinson down twice with hurtful blows, before the referee mercifully stepped in during the eighth round. Hamed afterwards comforted his victim, stating he was a true champion and doing his best to put an end to the bad blood between them.

On the British leg of the Bruno-Tyson undercard, Hamed put Said Lawaal out with two punches in a 35 second affair. Then the Hamed road show came to Newcastle. The telewest arena witness him enter the ring on a kings chair, with 6 men carrying him to the ring. Ian Darke, commentating for sky sports, put it best. “Woe betide any boxer who tries this when they can’t fight”. However undefeated Daniel Alicia was not here to collect his cheque and leave without causing a fuss. He embarrassed Hamed in the first, putting him down with a straight right for the first time in his career. Hamed rose quickly, sarcastically acknowledged the shot, and then dished his own punishment out in the next to win by second round stoppage.

It was in 1997 where Hamed moved up further in class. Tom “Boom Boom” Johnson, the IBF featherweight champ, came to London for a unification bout. Hamed did himself no favours in the build up, taking Johnson’s remark about it being a fight to the death too far by saying “you’ll end up in a graveyard”. Johnson had lost relatives to drive by shootings, and Naz, no doubt with promoter Frank Warren’s insistence, would later apologise for his comments. The action itself again showed how amazing Hamed was at this time. He lost only one round against an undoubted world class talent, and there became serious talk of him doing what few British fighters ever have, and crack the American market.

Frank Warren secured Hamed coast-to-coast coverage across the States, for his May 1997 clash with Billy Hardy. Hamed was always going to win; everyone outside the affable Sunderland natives’ camp knew that. Yet once again it was the manor in which he did it which would get him the attention. Knowing there was a huge opportunity to impress, he took full advantage. The 90 seconds witnessed two brutal knockdowns, the vivid memory of which being Hardy clearly in excruciating pain from the broken nose he’d just received. Hamed’s farewell to the UK came in the form of yet another superb display, versus tough Argentine Jose Badillo. Hamed, determined to put on a show for his hometown Sheffield crowd, toyed with his opponent for 7 rounds, in the manor he did with Beard and Bloomer all those years ago. Yet again, he had made a seasoned pro look far out of his depth, and the one sided hammering sent the crowd home delighted. Or the majority at least.

By this time, those in the trade who had already voiced their discontent had grown a little louder. Hamed’s taunting and showboating was getting shown to a larger audience and with it came more opinions on his style. And it was down to opinion. You’re idea of self-confidence confidence might be mine of arrogance; yours of taunting is mine of psychology and gamesmanship. Trade magazines were divided. Some writers heralded the master class of boxing, others criticised the bullying they felt was going on.

I’ll finish this section by leaving it at where I felt Hamed’s rise peaked- his American debut. The hype was immense for the British fighter, who had just signed a multi-fight contract with HBO. He was to take on Kevin Kelley, a former champ himself, with just one blemish on his record. Kelley was furious at all the attention Hamed received. The fight was in his home town of New York, yet it was Hamed who was billed as the attraction. It made Kelley determined to spoil it all.

He came so close to doing just that. The time it took for Hamed to get to the ring made Kelley even more livid. When the action got under way, Hamed seemed too eager to impress, looking too hard for non-existent openings whilst forgetting about his defence. In the first round, Kelley tore up the script and put Hamed on the floor. He’d manage to do this twice more, tasting the canvas himself in the process. Hamed looked in danger of being stopped, yet pulled off the win, by knocking Kelley out in the forth round of a truly amazing contest.

I have classed the Kelley fight as the peak of his career for a number of reasons. People may differ, and put his peak either before or after this time. I feel his best performances were in the time I’ve covered, with only fleeting glances of his superb talent evident after this. There are a number of reasons for this, which I’ll attempt to cover in the second part. For now, perhaps I’ve at least served to remind you that Naseem Hamed was an outstanding fighter, at least once upon a time.