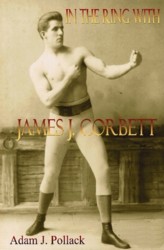

13.09.07 – By Zachary Q. Daniels: The second installment of Adam Pollack’s series of books on the heavyweight champions, In the Ring with James J. Corbett, picks up where his previous book on John L. Sullivan leaves off, reviewing the career of the second champion of the Queensberry era. The book employs the same meticulous approach to research as the earlier title, with careful citations to primary sources drawn primarily from local newspapers where particular fights were held, and continues the focus on the fighter’s boxing career rather than extraneous details of a fighter’s personal life. However, bouts are placed in their proper historical and social context and a sense of the issues influencing the fight game is given..

These qualities are what distinguish Pollack’s work from standard boxing biographies, and make them rich resources for both boxing fans and experts. Building on the approach begun in the earlier work on Sullivan, Pollack’s text in this volume is crisper and more “readable” than the first installment of the series – which, while chock full of excellent information became a bit bogged down in detail in places.

These qualities are what distinguish Pollack’s work from standard boxing biographies, and make them rich resources for both boxing fans and experts. Building on the approach begun in the earlier work on Sullivan, Pollack’s text in this volume is crisper and more “readable” than the first installment of the series – which, while chock full of excellent information became a bit bogged down in detail in places.

However minor this deficiency in the earlier work, it has been more than remedied in this one. The result is a book that breaks new ground in detailing Corbett’s career and does so in a manner that maintains interest throughout.

Pollack covers Corbett’s early career in California in great depth, focusing on some of the early “hippodromes” in which Corbett engaged from the start of his career in 1886. A hippodrome, as Pollack explains, is “either a fraudulent contest with a predetermined winner or at least one in which the fighters were thought to be going through the motions, . . .” Corbett, apparently, engaged in quite a few of these sorts of fights early in his career, mostly as exhibitions, both before and after his important early fights with local rival Joe Choynski. Throughout his early career, Corbett divided his time between participating in exhibitions, and working as a boxing instructor, or “professor” at a prominent San Francisco athletic club.

Perhaps partially as a result of this, Corbett did not have many official “fights,” up to his famous 61-round bout with Australian contender Peter Jackson in 1891. Corbett’s early bouts with Choynski, particularly their memorable 1889 encounter, are reviewed in detail, with primary accounts from local papers providing first hand information on these bouts, which is the defining characteristic of Pollack’s approach. The Jackson fight is of course covered extensively, with particular attention focused on the extensive negotiations to determine the site and rules governing the bout. As with the 1889 bout against Choynski, in reviewing the 1891 Jackson fight, Pollack utilizes multiple primary source accounts to give a full picture of this significant bout.

So too it is with Corbett’s classic title winning effort against an aging John L. Sullivan in 1892 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Great attention is devoted to the pre-fight build-up to the historic Sullivan-Corbett match, which puts the bout in its proper context. While often viewed retrospectively as a “passing the torch” fight where a long-time champion in decline inevitably loses to an up and coming contender, contemporaries viewed the bout as potentially much more competitive, and many thought Sullivan would emerge the victor over the relatively unproven Corbett, whose only significant victory was over local rival Choynski. His draw with Jackson in their match had provided further evidence of Corbett’s qualifications as a contender, but outside of this, his record remained a bit suspect to some observers of the time, and there was legitimate question before the fight whether he could handle Sullivan. Of course, this proved to be unfounded, as Corbett knocked Sullivan out after 21 relatively one-sided rounds. Sullivan had some moments, particularly early in the fight, but as the fight went on his lack of conditioning and heavy-drinking lifestyle betrayed him, and he was knocked out. In what was considered at the time something of an upset, Corbett had won the title.

One of the most interesting things that emerges from Pollack’s review of Corbett’s championship reign is how similar many of the issues were to those that are common in the fight game today. Although Corbett was extremely inactive by modern standards, the reasons for that inactivity are not unlike those which sometime prevent or delay major fights from being made today. Because Corbett could make more money acting on the stage than he typically could by risking the title against deserving challengers, he had long periods where he did not fight at all competitively. Similar to many of today’s fighters, when he did defend the title, he chose to do so against fighters who were not perceived to be much of a risk, such as an aging Charley Mitchell in 1894, or the crude Tom Sharkey in 1896 – rather than fighting more deserving challengers such as Peter Jackson or Bob Fitzsimmons.

It is also interesting to observe that Corbett was justifiably criticized for both his inactivity and his choice of opponents by the press of the day, something Pollack’s book extensively documents with quotes from these primary sources. Even though there was still a great degree of racism in the sport, and in the society generally, the press, overall, seemed supportive of Jackson’s right to challenge for the title, and Corbett came under criticism for not making the match in the early years of his title reign. Corbett was also criticized for avoiding the challenge of Australian Joe Goddard, who had established his qualifications as a challenger by beating Joe Choynski, among others. Goddard eventually lost before a Corbett match could be made, essentially rendering his challenge moot. Corbett continued to be criticized for having not taken this fight, and for not making a fight with Peter Jackson before the latter gave up and returned to Australia. Pollack, however, makes clear that there were indications that Jackson himself was not entirely eager to take the match himself, and that some of his public protests may have been calculated to embarrass Corbett and enhance his own reputation, rather than designed to set up a fight. Regardless of who was to blame, the fact was they never did fight while Corbett held the title.

Similar ambiguity is present in the back and forth accusations that preceded the eventual fight between Corbett and middleweight champion Bob Fitzsimmons in 1897, which are covered extensively in this volume. This match was under discussion from at least 1894 forward, but never happened until 1897. Challenges and discussions went back and forth, and a fight was almost made in 1895 before Fitzsimmons backed out at the last minute due to potential legal penalties that might ensue if they fought, but no fight was held until March 1897. In the interim, Corbett continued his acting career, and held periodic exhibitions, “defending” his title (sort of) once against the rugged Sailor Tom Sharkey – who, some contemporary reports argued, got the better of what was ultimately declared a draw in 1896. Regardless, Corbett kept his title, and negotiations proceeded for a Fitzsimmons match. Pollack uses contemporary reports on the Sharkey fight, and for the build-up to the Fitzsimmons match to shed light on these developments.

Of course, Corbett went on to lose his title to Fitzsimmons as a result of the famous “solar plexus” punch he delivered in the 14th round, knocking Corbett out. As with his book on Sullivan, Pollack provides scant coverage of the actual title-changing match in this book, preferring to present this in his planned biography of the next heavyweight champion, Fitzsimmons. However, the context, significance, and background to this fight are well-covered. Not much attention is placed on Corbett’s periodic post-title career, an omission which will be addressed in future volumes. However, as with his championship reign, Corbett was not particularly active, so this is not really that serious a deficiency.

Ultimately, the picture that emerges from Pollack’s book is one of a champion who, as he puts it, was “about the money more than the glory,” and who consequently only defended his title 3 times between winning the title against Sullivan and losing it against Fitzsimmons. Clearly, Corbett viewed the heavyweight championship more as a vehicle for his attaining his money-making aspirations, rather than an end in itself. And, in an era when fight purses – which may have potentially brought legal consequences, and certainly contained the risk of injury – were nowhere near what they are today, perhaps this is not so blame-worthy as it seems to modern observers.

One of the lessons that can be learned from the sort of review of primary sources which Pollack’s books provide is that it is important to judge a fighter’s career in the context of their times, and by the standards that prevailed at the time. While Corbett came under contemporary criticism for his failure to defend the title regularly and to face the most deserving challengers, his pursuit of fame and fortune in theatrical and other non-boxing enterprises was not atypical of the champions of this era. The information provided from the primary sources in this book allows us to make this sort of assessment, free of the distortions imposed by the interpretations made in many retrospective analyses of these events. In unearthing this primary source material, Pollack has made a unique contribution to literature available on James J. Corbett, and substantially enhanced and expanded on our understanding of the career of this sometimes overlooked early pioneer in boxing history.

The book may be ordered in hardcover www.lulu.com/content/1185889 and soft cover www.lulu.com/content/1183491 versions at Lulu.com.

To read more articles by Mr. Daniels, please visit The Mushroom Mag:

http://www.eatthemushroom.com/mag