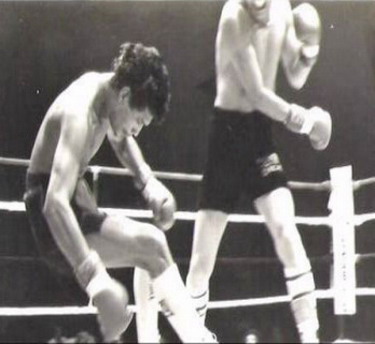

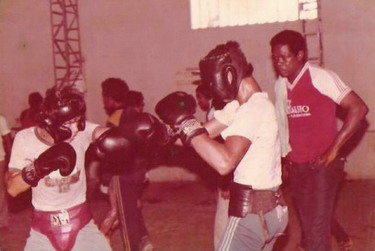

03.01.08 – Jaime Castro-Núñez: Robinson Pitalúa arrived to Miami and shared an apartment with other boxers at Lake Laguna West, 301 NW 109th Ave. In Miami, he developed a new routine that included workout, trotting, boxing lessons, and ESL classes, so he could attend college and work toward his medical degree. He fell into Brusa’s hands in July and on August 23, 1985, Pitalúa made his US debut against Nicaraguan Mauricio Guadamuz, who was decked with a powerful left hook 1:23 into de second round.. Thirty days later, on Friday, September 20, he faced Julio César González at the Tamiami Fairgrounds Auditorium. Pedro Vanegas remembers that Friday night with nostalgia: “His parents, siblings, Robinson Suárez, and I gathered together at his house on Monteria’s 41st Street and had a couple of drinks while waiting for the outcome. We talked about his future and on Saturday, around 2:00 a.m., he phoned his mother to inform he had decisioned “Tarzán” González.” He had raised his professional record to 6-0.

On Sunday, September 22, he granted a radio interview and then went swimming with fellow boxer Jaime Polo in a lake behind his apartment. They took a skiff into the middle of the lake and decided to jump into the water, but all of a sudden Robinson disappeared. Polo returned to the shore and started to look for him. Around 3:30 p.m., Mr. Rafael Pitalúa received a phone call:

“Rafael, this is Amilcar. Does Robinson know how to swim?”

“Yes, he does. Why? What’s going on?”

“He went swimming with a friend, but we can’t find him,” replied the trainer.

“Don’t tell me anything else, Amilcar. Robinson drowned. Tell me the truth…”

“We thought Robinson was kidding. He was a playful kid, so we’re hoping he was hidden somewhere, laughing at us,” recalls Robinson Suárez. “We received a phone call around two o’clock…that was the beginning of the nightmare! We received calls from Panama, the US, Cuba, Dominican Republic, and even from Germany. They were expressing condolences, but up to that point nothing was official. We hoped he was playing,” says Zenón Vellojín. Up in Miami, police divers were searching the bottom of the lake, but they found nobody. Early Monday morning, September 23, divers tried again. At 10:45 a.m., they pulled Robinson Pitalúa’s body from the cold lake. He had turned twenty just nineteen days before. On Wednesday, September 25, the corpse was sent to Monteria, where he was buried.

More than 60.000 people gathered at Montería’s small airport and narrow streets to receive the hero. Kids, teenagers, young adults, adults, parents, and grandparents, wealthy and poor people, men and women, left their homes and followed the coffin from the airport to the cemetery. Monteria collapsed due to the myriad of people on the streets. No other Monterian has received such honor.

But the cause of Robinson Pitalúa’s death is still a mystery, at least to his relatives and those who knew him well. Mr. Rafael Pitalúa states: “I don’t believe he drowned. Robinson was so good at swimming that when he participated in the World Championships, the Germans advised him to quit boxing and practice swimming. The physician who performed the necropsy told me that Robinson could live up to eighty years. He had a swelling on his head that still bothers me. The only thing that tranquillizes me is that I was a good father and I gave him the advice I had to. I have the hope of seeing him again in the Kingdom of God.”

Pedro Vanegas says: “Part of the training we used to do included swimming on the Sinu River to fortify muscles”. Zenón Vellojín argues: “We always have managed two theories. We know that before going to the lake he had received warm massages. The water of the lake where he drowned had the particularity of being warm on top, but cold further down, so it’s possible that he’d cramps, as it has always been said. The death certificate talks about death by immersion. What bothers me is that his lungs had no water and that blow in his head. The drowning story doesn’t convince me.”

Twenty-two years have passed since the morning in which Robinson Pitalúa went to the lake behind his apartment in order to swim and enjoy. His relatives talk about Robinson with firm voice and without a single tear. Time has healed the wound. In order to remember Robin forever, the Pitalúa-Támara family placed on the living room’s wall all sort of medals, photographs, certificates, and trophies. The sensation of being in front of that wall is indescribable. Rest in peace, champ!

Acknowledgement:

This article is based on my soon-to-be-released book La Canción de Robinson (Robinson’s Song). I would like to take the opportunity to thank the Pitalúa-Támara family, Tania Castro, Olga Núñez, and Oscar Sánchez Oviedo for their unselfish help and support.