15.09.08 – By Michael Klimes: During my visit to New York in May with my father I discovered the best second hand book shop. It’s called Strand Bookstore on the corner of Broadway and 12 Street. When I first entered that building it was labyrinth of shelves and I spent several hours there, happily advancing through the different sections of my newfound heaven. The Sports Section was located downstairs and had a splendid assortment of titles from the all physical occupations humanity has invented.

15.09.08 – By Michael Klimes: During my visit to New York in May with my father I discovered the best second hand book shop. It’s called Strand Bookstore on the corner of Broadway and 12 Street. When I first entered that building it was labyrinth of shelves and I spent several hours there, happily advancing through the different sections of my newfound heaven. The Sports Section was located downstairs and had a splendid assortment of titles from the all physical occupations humanity has invented.

I was happy to find that in many of New York’s bars I had seen residues of the city’s once glorious boxing heritage preserved through grainy pictures hung up on the walls. I was even gladder that such a brilliant bookstore was a bastion for the literature which has been inspired by men punching each other. Later I reflected that boxing needed all the allies it could muster to survive. Bars and bookstores are two good friends for a person to have if he is in trouble. For me, bars, the ring and bookstores are sacred places.

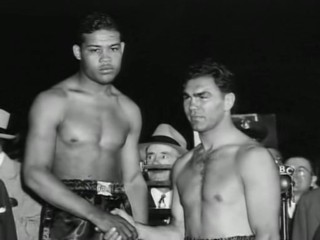

In a rather prominent way, the books I purchased had a lot do with New York and New Yorkers. David Margolick and Douglas Century are two journalists who have written considerable works on the important subjects of the rivalry between Joe Louis

versus Max Schmeling and the legendary Jewish pugilist Barney Ross. Margolick’s book is called Beyond Glory Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink while Ross’s biography is economically called Barney Ross. The former book is the much longer work and shines a microscopic spotlight on the complex historical background that permeated the sport of boxing in the 1930s. By contrast Century’s account of his subject is much shorter, almost pocket sized.

Century is a New Yorker himself, at least that’s what it says in the book sleeve and he probes the paradoxical nature of Ross’s life. Ross was born in Chicago in 1910 to a very Orthodox Jewish family. The author writes at the beginning of Part 1 that Ross was, “a kohain, born into the ancient priestly caste, and reared by his father to become not a pugilist but a Hebrew teacher and Talmudic scholar.” This quotation captures the bizarre dichotomy that ran through Ross’s life. He felt deeply attached to his Jewish roots and family background yet he fell into the materialistic trappings that numerous athletes invariably do. There was also a strange echo between the discipline that Ross had when he was fighting and the lack of it after he left the ring. So he only found the discipline his father wanted him to have in a fighting tradition that he never wanted his son to be part of. Century emphasises the fighting history that Ross pulled onto create his own identity separate from his father’s. The Chicagoan had a plethora of forbearers in Benny Leonard, Al Singer, Leach Cross, Sid Terris and Abe Attell. The line stretched right back to Daniel Mendoza, the granddaddy of Jewish boxers.

Ross established himself as a big marquee name in both Chicago and New York. These two cities became the axis on which his life rotated and when Ross retired, he was incapable of deciding which town he belonged to. During his career, Ross tangled with the finest of his generation. He was one of the first world champions in three different weight classes and took on Henry Armstrong, Tony Canzoneri, Jimmy McLarnin and Battling Battalino. During his retirement, Ross was restless and found a new home in the Marine Corps in his early thirties. He went to the Pacific where he fought in Guadalcanal and became a war hero. His feats of courage were extraordinary but unfortunately he contracted malaria which he tackled by taking morphine.

He soon became a heroin addict and had a highly publicised battle to get himself off the drug. Another event of huge historical significance Ross devoted himself to was the creation of Israel and he smuggled weapons the newly established nation in through his illicit contacts. He even offered to lead a group of Jewish war veterans under, “the George Washington Legion, a prospective Jewish-American armed force patterned on the famed Abraham Lincoln Brigade of the Spanish Civil War. Barney was joined by the legion’s British-Jewish organiser, Major Samuel Weiser, who had been on the staff of Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery in the war.” Furthermore, Century highlights how Ross, “allied himself with the so-called Bergson Group, a small, intensely driven band of militant Zionists.”

The final event in the saga that was the ex-champion’s life was that he appeared in the Warren Commission Report which investigated the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Jack Ruby was a childhood friend of Ross; a friendship that was forged during their young years growing up together on Chicago’s West Side. Century says Ross, “was interviewed in the FBI’s New York office twice: on November 25, 1963, and then again on June 4, 1964. He freely admitted his friendship with Ruby, told how Ruby used to be present at everyone of his prizefights.” He also, “appeared [at Ruby’s trial in Texas in November 1964] as a character witness for the defence.” Ross’s loyalty to Ruby revealed something extremely important about his value system as, “he remained true to the code of Chicago’s West Side; loyalty to old friends trumped everything, trumped negative headlines, trumped political shame.” Unfortunately, Ross colourful lifestyle contributed to his early demise and he died at the age of 57 on the 17 January, 1967 at 10 a.m.

Earlier, I said that Margolick’s book is much thicker and discusses the Max Schmeling versus Joe Louis rivalry. Indeed, his work is encyclopaedic in its erudition and meticulously researched. It is clear the author worked extremely hard to go over his subject matter so thoroughly that no one could repeat the mission he had undertaken. What is refreshing about Margolick’s approach is the sublime ease with which he handles historical sources. The majority of his material is from the contemporary newspaper reports and the copious notes in the bibliography demonstrate his forensic approach.

There are three lines of interpretation running through Beyond Glory which are articulated by the newspapers of the day. Firstly there is the Afro-American interpretation of events, embodied in the two most important publications for blacks during that time, the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier. Secondly, the Jewish interpretation of events is dealt with, mainly through the eyes of Joe Jacobs, Mike Jacobs and Joe Gould, the triumvirate of Jewish promoters who all played decisive roles in the Joe Louis versus Max Schmeling rivalry. Thirdly, there was the Nazi-German interpretation of events that came from the prominent German sport’s magazine Box-Sport and Angriff, “the mouthpiece of Nazi Germany’s Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels.”

Margolick is brutally honest about the figures he discusses and is very clear sighted about their flaws. His style gets to any observations he is making quickly. The author is forced to confront very sensitive questions like how did Max Schemling’s relationship develop with the Nazis and was he a Nazi? Margolick is adamant that he was not but there remains an ambiguity about Schmeling as he always did and still does escape any black and white definition we want to pin on him. These two quotations are telling:

1) “For the ever pragmatic Schmeling, the new political situation must have seemed both disturbing and promising. On the one hand, many of Schmeling’s artistic and intellectual friends were enemies of the new Reich, or Jews, or both. On the other had, Hitler, unlike prior German leaders, loved boxing.”

2) “Schmeling never said any more than he had to stay in the Nazis’ good grace. He did not sport Nazi rhetoric or wrap himself in the swastika. It will never be clear whether this was a matter of conviction or calculation, or even whether the decision was his or someone else’s. But for all those concerned, things worked out quite nicely. Whenever the Nazis asked him to pitch in, he obliged. Never did they ask him to do anything that would unduly foul his American nest, which produced great capital for both Schmeling and the regime.”

The above quotations encapsulate the thrust of the central theme steaming through Margolick’s book. The fundamental reason why the Joe Louis and Max Schmeling fights transpired was due to money.

The Nazis and pretty much everybody in Margolick’s book comes off as ethically frivolous in the sense that they would compromise their ‘principles’ to earn the largest amount of money possible. The last thing one would want to call the Nazis is ‘principled’ but it is important to remember that as ghastly as the Nazis were, they did have a ‘value system’, albeit an extremely abhorrent one which they were prepared to compromise to make lucrative profits. This apolitical and amoral pragmatism meant doing business with shifty Jewish promoters in New York, the nexus of Jewish life before the establishment of Israel. When Joe Jacobs, a Jewish raconteur and Schmeling’s manager/promoter came to Nazi Germany with Schmeling who was his best asset, he was present for Max Schmeling’s bout against Steve Hamas in Hamburg on 10 March 1935. Here, Schmeling started his ascendancy back into contention after he lost the heavyweight championship to Jack Sharkey in 1932. After Schmeling’s lopsided victory, everyone in the arena extended their arms for the Nazi salute. Jacobs had to raise his arm as well, “as if half heartedly hailing a cab.” There is a humiliating picture of Jacobs in Beyond Glory, caught red handed in the act. His reputation never recovered afterwards.

The contrasts and connections between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling as boxers and personalities are intriguing. Louis was never roped into politics in quite the same way Schmeling was as he had fewer balls to juggle and seemed to talk a lot less during interviews. The team which surrounded Louis including his trainer Jack Blackburn, his ‘investors’ Joe Roxborough and his Julian Black collectively ensured the image of Louis was of the respectable, honest, hard working black man who recognised the boundaries and never crossed them like his wayward predecessor, the insolent Jack Johnson. By contrast, Schmeling was bombarded with political questions but always tried to avoid them. The German always had a dogged determination to maintain his presence in America, even it if was very hard in the face of bitter press criticism. However, Schmeling knew and the regime he served recognised that the country where boxing had genuine relevance was the United States.

When it came to them as fighters, Louis was the far more gifted athlete and technically proficient boxer. He was the Socrates of his sport: The greatest classicist of the heavyweights who ever laced up gloves. His jab and compact punches have been just about the most beautiful ever thrown. Although Schmeling was not as talented as his opponent, he was an extremely shrewd operator. Actually, Schmeling fit the German stereotype precisely. He was scientific, methodical, efficient, cautious and patient. His money punch was his powerful right hand. Running up to their first encounter on June 19 1936 Schmeling had noticed a flaw in Louis classical style, he never brought his left hand up properly after he released a jab, thereby leaving the left side of his face exposed to a well timed counter-punch. Schmeling exploited this ruthlessly as he stopped Louis in the twelfth round.

The whole of Harlem, the home of Louis’s fan base in New York was eerily silent after their hero had been thoroughly outclassed. Louis’s lax preparations before the fight had caused him to take an embarrassing beating. Their rematch took place two years later on June 22 1938 but a fascinating history of corruption and double dealing by cunning promoters unravelled beforehand. The controversy demonstrated how politicised and profitable boxing had become through the fusion of publicity and nationalism.

Margolick sums up the dilemma of the heavyweight division at the beginning of 1937, “The new year opened with the boxing world in a fix. Braddock was the champion, but no one gave him much of a chance to beat either Louis or Schmeling. The only questions were who would beat him first, whether racial or international politics would help make that choice, and whether the two challengers would fight each other before it happened.”

After Schmeling beat Louis, it was his right to challenge for the heavyweight championship as he had earned it. Tragically for the German, Joe Gould, the promoter of the-then heavyweight champion Jim Braddock wanted to get the best purse for his fighter possible and that meant fighting the bigger name in Louis. Louis’s promoter, Mike Jacobs wanted to do business with Gould because he knew that if Schmeling won the title by beating Braddock, it would irreparably damage Louis’s chance of winning the championship as a fundamental shift in the boxing world have taken place. America would no longer be the ‘owner’ of the title and Nazi-Germany would be able to sit on it indefinitely and Louis, even if he came back, would not be able to get his shot. If Louis would be unable to fulfil his title ambitions, it in turn would damage Jacob’s ace commodity and his profits. Therefore, Gould and Jacobs had to locate an excuse so they could engineer a coup under Schmeling’s nose.

Gould found the convenient excuse in a minor Anti-Nazi League boycott against Schmeling. The Anti-Nazi League did not want him to fight Braddock. Gould and Jacobs defended their cheap scam against Schmeling by appealing to altruistic motives.

The stances of some public figures against the boycott are worth noting. Margolick observes the group, “was headed by the prominent lawyer Samuel Untermyer…for all the demonising he endured in the German press, Untermyer actually opposed the fight boycott originally.” Furthermore, “the boycott organisers tried repeatedly to enlist the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People], but Walter White balked. The group opposed Hitlerism but felt the movement had been hijacked.” White sided with Schmeling. Naturally Schmeling was furious that his title shot at Braddock was removed by consummate swindlers. Jacobs then stepped in and negotiated for Braddock to fight Louis as an alternative on June 22 1937. Louis became world champion on that date. As for Schmeling he got so pissed off that he cabled Joe Jacobs and “declared that he was done with America.”

Nevertheless, the shadow of Schmeling hung over Louis like the shadow of Ali over Frazier. Both Louis and Frazier had to beat their biggest rivals to demonstrate they were the undisputed heavyweight champions of the world. Louis had to vanquish Schmeling and it was the type of situation where a rematch had to be demanded. It would have been criminal if there had not been one. Some fights are destined to happen.

Their rematch was saturated with anticipation. In his training camp at Pompton Lakes, Louis received visits from his boxing comrades as they all realised, consciously or not, that this was not just a fight for the heavyweight championship of the world, it had taken on a metaphysical meaning. The support they gave him is touching, Margolick writes:

“Preparing Louis for Schmeling became a joint effort. Noting that Louis didn’t retain things for very long, Armstrong gave him a refresher course on rushing in and swinging. Even Dempsey, who’d liked Schmeling, [they looked uncannily similar in appearance] and written off all Louis (and all black boxers) after the 1936 fight, pitched in, almost as if it was his patriotic duty. He paid a clandestine visit to Pompton Lakes, telling Louis how to roll away from punches more easily. He then left the camp, only to order the driver back. ‘You fight him the way you did the last time and the way you boxed him today and you got to get licked again!’ he scolded Louis after rejoining him. He then removed his coat. ‘Move into me!’ he’d scolded. ‘Come on! Move! Bend! Get your tail down! Don’t wait! Start punching!’ Louis must have thought he was nuts, Dempsey said, but he didn’t give a damn; he was just trying to help him. Maybe he had.”

The instructions from Dempsey produced results. Louis stopped Schmeling in the first round. Schmeling’s career was then effectively over as World War Two broke out. He became a paratrooper during conflict and returned to the ring in the post-war years, finally retiring in October 1948 at forty three years of age. During the war, Schmeling experienced two considerable losses. His friend Arno Hellmiss, “surely the most universally known sports broadcaster in German history” who travelled with him to America and broadcast his bouts back to the Fatherland was killed on June 6, 1940 in an ambush in France. He was quickly forgotten by the regime. Margolick says, “It was not Schmeling’s only loss that spring: six weeks earlier, Joe Jacobs had died of a heart attack. He was forty two years old.”

Louis fought on too long and fell into ill health with drug abuse and chronic financial problems. His grinding decline was very sad. In 1954, both ex-champions were reunited. During part of that trip Schmeling went to New York and visited Jacob’s grave to pay his respects. He also encountered James Farley, the ex-New York state boxing commissioner who became a top Cola-Cola executive and offered Schmeling a job in West Germany that made him into a millionaire, establishment figure and philanthropist.

Unfortunately, Louis had heart surgery in 1977 and afterward had a stroke that left him paralysed. He died of a heart attack on April 12, 1981 at the age of sixty-six. Schmeling last much longer and died on February 2, 2005 at ninety nine years of age.

Douglas Century and David Margolick have done an exemplary service to three extraordinary lives. The fruit of their labours are for our wider pleasures. They have both summoned not only the facts but also the feeling of the eras which created these fighters. I am sure if Joe Louis, Max Schmeling and Barney Ross were still alive and read these books, they would be happy. They can’t do that so the fans have to do it instead. To my mind, this is the best eulogy for three men who were once, to play off the name of that classic documentary about the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ called When We Were Kings – They were once kings.

David Margolick, Beyond Glory Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink, 423pp, Alfred A. Knopf, 2005, $24.95, 0-375-41192-5

Douglas Century, Barney Ross, 209 pp, Schocken Books, 2006, $19.95, 0-8052-4223-6

David Margolick, Beyond Glory Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink, 423pp, Alfred A. Knopf, 2005, $24.95, 0-375-41192-5

Douglas Century, Barney Ross, 209 pp, Schocken Books, 2006, $19.95, 0-8052-4223-6