By Mike Casey – Now here’s one for you. When people sit down to talk about the great middleweights, how come the name of Freddie Steele so rarely enters the conversation? Like a ghost trying to make its presence felt to mortals, Freddie seems to hover in a vacuum that is tantalisingly out of reach. Up there in the celestial heights, he must feel sorely tempted to get his booming left hook out of mothballs and throw a few shots in desperation. He hears people talking about the Michigan Assassin, the Pittsburgh Windmill, the Toy Bulldog, the Harlem Flash, the Shotgun and Marvelous Marvin.

By Mike Casey – Now here’s one for you. When people sit down to talk about the great middleweights, how come the name of Freddie Steele so rarely enters the conversation? Like a ghost trying to make its presence felt to mortals, Freddie seems to hover in a vacuum that is tantalisingly out of reach. Up there in the celestial heights, he must feel sorely tempted to get his booming left hook out of mothballs and throw a few shots in desperation. He hears people talking about the Michigan Assassin, the Pittsburgh Windmill, the Toy Bulldog, the Harlem Flash, the Shotgun and Marvelous Marvin.

But no Tacoma Assassin. That’s what they called Freddie Steele, the wiry, thunder-punching kid from the Evergreen State of Washington.. This writer makes no case for Freddie being one of the elite middleweights of all time, as in top three or top five material. He might not even be a top ten candidate. Let us remember that the middleweight division is the richest and most fertile ground from which to select our favourites. Try fashioning your own all-time Top 20 without feeling that you have insulted a host of genuinely great boxers by leaving them out. Believe me, you can work up quite a guilt complex about it if you genuinely love and care for the many magnificent men who have graced the stage.

I have never truly known where Freddie Steele stands in the great historical pantheon, but I am a little miffed that he seems to have become the invisible man.

Ah, but there are always the guardian angels looking out for the straggling sheep that get divorced from the flock. In planning this tribute to Freddie, I knew that I had something of a spiritual brother in Dan Cuoco.

Dan, who heads up the esteemed International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO), has long been a great fan and champion of Freddie Steele.

“Freddie is one of my all-time favourites. He has never received his just dues as a great champion and one of boxing’s all-time great punchers. His resume of knockout victims is quite impressive: Ken Overlin, Vince Dundee, Gus Lesnevich, Ceferino Garcia, Fred Apostoli, etc.

“Freddie’s overall record of losing only five fights out of a career total of 162 is outstanding. And his list of opponents is a virtual who’s-who of his era.”

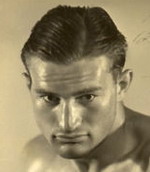

Big punchers invariable have a lean and languid look about them, and Freddie Steele was almost wiry in appearance when he first started out in the professional ranks. But the glint in his eye, the solid chest and the classic sloping shoulders were indicative of the great power he carried in his fists.

California Hall of Fame member, Hap Navarro, matchmaker at the old Hollywood Legion Stadium between 1953 and 1955, has always had the highest regard for Steele. Hap told me: “Freddie was a gangly sort as a fragile welterweight at the start of his pro career, long before he hit it big. But he could box with the best and had a devastating punch. Check out the film of his two round annihilation of a rising Gus Lesnevich at the LA Olympic Auditorium.”

Steele did indeed make a terrible mess of Lesnevich in that short-lived fight on November 17, 1936. Freddie was the reigning world middleweight champion at the time and in his glorious pomp. The opening paragraph of the United Press report gave only a hint of the violent story that Freddie had written: “Freddie Steele, world middleweight boxing champion, snapped lethal punches with both hands last night to technically knock out tow-headed Gus Lesnevich of Hackensack, NJ, in the second round of a 10-round overweight match.”

A crowd of 10,400 at the LA Olympic saw Steele twice hammer the tough Lesnevich to the canvas in the opening round and inflict two severe eye gashes.

Gus had been campaigning for four years as a professional and had never previously been floored. But he was immediately in distress against Steele, hitting the deck for the first time from a ramrod straight left. Freddie had already cut Lesnevich’s right eye, and so deep was the wound that the blood showered over Gus’ head and shoulders.

Gus took a nine count on one knee and showed tremendous fighting spirit on rising.

He roared back to shake Steele with two fast lefts, but Freddie just shook his head and drilled Gus again. Lesnevich was toppled for the second time, although he was up quickly and didn’t take a count. Once again, Gus showed his pluck and determination by fighting back, and he belted Steele with a solid shot to the chin before the end of the round.

But the game prospect from New Jersey, who would go on to win the light heavyweight championship, was living on borrowed time at the LA Olympic. Freddie wasted no time in wrapping up business in the second round. His sharp punches inflicted another deep cut, this time over Lesnevich’s left eye, and then Gus was toppled for another nine count as the ferocious blows kept coming. Gus’ handlers threw in the towel as blood covered the face of their brave charge. Freddie, weighing 158lbs, had spotted Gus five pounds without being remotely inconvenienced by the disadvantage.

Tougher

Boxing was tougher in Freddie Steele’s time. It just plain was. The competition was so fierce and so consistent that fighters in general had a considerably shorter career span than their counterparts of the present era. Consider these sobering facts: Freddie Steele was a retired fighter by the age of twenty-eight, having had his first professional fight at fourteen. He campaigned for nearly fifteen years, won the world middleweight championship and regularly clocked up more than twelve fights in a calendar year.

Was he any the worse for wear when he hung ‘em up? No. He became a very successful actor and a very shrewd businessman.

Dan Cuoco picks up the early story of the Tacoma Assassin: “Freddie Steele was a boxing prodigy. As early as age six he dreamed of a career as a boxer. His parents hoped he would outgrow the idea. But he didn’t. Every day after school his friends would find him in his backyard, imitating the style of his idol, Tod Morgan.

“At age twelve, against his parents’ wishes, Freddie started attending a local gym in Tacoma, Washington. At first the gym’s proprietor, Dave Miller, didn’t take Steele seriously. After all, Freddie was just a scrawny, under-age adolescent.

“But Freddie was very determined and continued to show up at the gym every day. He studied the fighters in the gym and began imitating their moves. They took an immediate liking to him and began helping him whenever they could. Within months, their help started to pay off.

“Freddie began hitting the heavy bag with authority and making moves that surprised everyone in the gym, including Dave Miller. Miller was so impressed, he took young Freddie under his tutelage.

“After six months of extensive instruction, Freddie began sparring with the older professionals in the gym.”

Steele’s progress astounded everyone. He was quite obviously a natural, which presented Dave Miller with the age-old problem of how best to handle the wonderfully talented youngster in his charge. It doesn’t matter whether a prodigy is a gifted boxer, footballer or pianist. Do you give him full rein or keep him wrapped in cotton wool? Miller decided to let Freddie Steele off the leash, and how Freddie sprinted! He was just nineteen and a fully-fledged welterweight when he was matched with future middleweight champion, Ceferino Garcia, in a six-rounder at the Civic Ice Arena in Seattle.

Dan Cuoco writes: “The murderous punching, twenty-six year old Garcia was an established main eventer and was heavily favoured over his youthful opponent. But Steele, a murderous puncher in his own right, surprised everyone with a second round knockout. Six months later he proved the victory wasn’t a fluke by again knocking out Garcia in the second round.

“By his twentieth birthday, Freddie had engaged in 82 professional fights and his future looked bright. He had compiled a brilliant record of 72-2-8, with 29 KOs. He had avenged both of his decision losses in return matches.”

Fred Apostoli

It was against another future middleweight champion, Fred Apostoli, the so-called Boxing Bellhop, that Freddie Steele really got tongues wagging. Still eight months shy of his twenty-third birthday, Steele was already being described by the sport’s writers as a veteran. And indeed he was in terms of battles fought.

He and Apostoli waged a tremendous contest in the latter’s hometown of San Francisco on April 1, 1935, which won them a thunderous ovation from a crowd of more than 6,000 at the Civic Auditorium.

Both boys weighed 157lbs, but it was Steele’s greater experience that tipped the scales in his favour. Not that Freddie had an easy ride. The tough and clever Apostoli was a former national amateur champion and already a highly accomplished ring mechanic at the age of twenty-two. Employing a crouch, Apostoli perplexed Steele considerably in the early rounds.

After six stanzas, the fight was an even, thrilling duel as the young tigers stood toe-to-toe and winged punches to the head and body. It was in the sixth, however, that Freddie began to turn up the heat. Putting more steam into his punches, he really began to punish Apostoli hard to the body. The San Franciscan took the shots well, but Steele’s constant body attacks began to reap dividends.

Gradually, Apostoli was weakened by the consistent onslaught, to the point where he twice dropped to the canvas in the ninth round without being hit. The brave San Franciscan’s resistance was being viciously chiselled away by the stream of quality punches that were slamming into his midsection. One minute into the tenth round, referee Eddie Burns waved the fight off to save Apostoli from further punishment.

Steele’s reputation as a damaging puncher reached a frightening crescendo in Seattle just three months later. His third round destruction of former middleweight champion, Vince Dundee, could only be described as a slaughter. Referee Tommy McCarthy seemed to freeze like a rabbit in the headlights as he allowed the hapless Dundee to be savagely punished and floored eleven times. Finally McCarthy stopped the carnage after Steele threatened to quit.

Recalling the fight in 1969, Steele said, “I begged the referee to stop the fight in the second, but he wouldn’t do it. The fans were screaming that the fight should be stopped. In the third, after Dundee had been on the deck eleven times, I told the referee that if he didn’t stop it, I would leave the ring. He stopped it. Dundee wasn’t the same after that.”

Vince was taken to the nearby Providence hospital with a triple fracture of the jaw and concussion. He spent the entire night trying to regain his bearings and struggle free of the vacuum into which Steele’s blows had rendered him. Dr HT Buckner advised the shattered Dundee not to box for three months or more.

Freddie Steele could not be stopped and his coronation as middleweight champion was just a year away. On July 11, 1936, before his own adoring fans at Seattle’s Civic Stadium, Freddie challenged Eddie ‘Babe’ Risko before a crowd of 27,000. Local reporters described the contest as the biggest fight staged in the Pacific Northwest since Jack Dempsey had outpointed Tommy Gibbons at Shelby, Montana, thirteen years previously.

Steele was ready for the challenge and in peak form as he controlled the fight all the way. But what tough men they all were in Freddie’s day. Fighters shrugged off major defeats with the resigned and philosophical air of a horse flicking away the flies. Seven months before, Risko had stumbled into an absolute nightmare at Madison Square Garden in a non-title bout against the fearsome Englishman, Jock McAvoy, whose nickname of the Rochdale Thunderbolt said pretty much everything about him. The Babe was scuttled by the first punch of the contest, a terrific right, and proceeded to visit the mat a further five times before McAvoy blasted him out of the fight in two minutes and fifty-eight seconds.

Steele threatened to finish Risko in similarly quick fashion. In the first round, Freddie uncorked one of his big left hooks to deck the Babe for a count of seven. The omens were not good for the defending champion, yet thereafter he survived the storms that raged around him with admirable grit and skill.

Steele was consistently ferocious through the fifteen rounds of battle, mounting one withering body attack after another. Lesser men than Risko would surely have crumbled under the savage pummelling. Freddie’s sharp punches to the face so often had the effect of a slash from a sabre on his many opponents. One reads constantly of how the Tacoma Assassin’s blows would not merely tear the other man’s skin. They would open deep and damaging cuts.

He opened cuts over both of Risko’s eyes, but the Babe was determined to hang in there and keep punching. Steele, seemingly tireless, rarely slackened his pace. Risko was stunned again in the tenth round when Freddie doubled up with a left hook to the chin and a left to the body.

But Steele was much more than merely an attacking force. He also displayed excellent blocking skills, preventing Babe from scoring effectively with short lefts to the head.

Risko, showing a world champion’s pride, never stopped trying to the end. His work improved in the later stages of the contest as he engaged Freddie in toe-to-toe warfare with some success. But the Babe had given too much away and simply couldn’t overcome the wide points deficit.

The Associated Press was glowing in its summation of Freddie: “Steele has done all his boxing on the Pacific coast. Just twenty-three years old, he has the height, reach and hitting power of a heavyweight.”

The Funny Side

For all his fiery determination, Freddie Steele was a man of great humour who could never help chuckling at boxing’s funnier side. When he made the first defence of his title against the canny and funky Gorilla Jones, Freddie was ready for the Gorilla’s tricks. They had met previously, and although Freddie had beaten Jones by decision, the Gorilla had suckered him with what appeared to be a bad technical flaw. Jones would jab and then drop his left low

Explained Freddie: “He left the left side of his jaw exposed. He was wide open for a right hand. I waited until about the fifth to throw my right. It was too good to be true. I threw it. But Jones was ready. He stepped back on his right foot and threw a right hand counter that almost tore my head off. I didn’t throw another right the rest of the fight.”

Steele would discover that Gorilla Jones had a sense of humour too when they clashed again for Freddie’s championship. In the seventh round of that battle, Freddie turned the tables by jabbing with his left and then dropping it. When the Gorilla took the bait, Steele dumped him on the canvas with a cracking right to the chin. Jones got up, fell into a clinch with Freddie and said, “You don’t forget, do you?”

Freddie Steele was flying, a man of destruction at the peak of his powers. Two more successful defences of his title quickly followed when he decisioned Babe Risko again and then knocked out Frank Battaglia in three rounds. But perhaps Freddie’s power was never more chilling or sudden than in his fourth round decimation of the clever and skilful Ken Overlin at the Civic Auditorium in Seattle on September 11, 1937.

Steele took some time to figure out Overlin, who stormed from his corner in the opening round and fired a succession of left hooks to Freddie’s stomach.

Steele boxed cautiously, knowing that he was up against a classy operator. Steele seemed to be waiting for Overlin to blow himself out, but Ken was all business and kept attacking, slamming a hard right and a left to Freddie’s body.

Overlin was obviously gambling plenty on a fast start and he maintained his hot pace at the start of the second round. He jabbed fast and forced Steele to give ground. Steele was patient, weighing up Ken and looking for the one opening that would turn the tide. But the champion couldn’t quite get his timing right and missed with a jab as Overlin scored with two solid left hooks to the head.

The Seattle crowd must have wondered in the early going if their Freddie had met his match. Overlin continued to jab effectively to close out the second round and enjoyed further success in the third as he repeatedly found Steele’s jaw with jarring lefts. Then came the first sign that Freddie was waking up and finding the range. He momentarily staggered Ken with a vicious right uppercut, but the man from Virginia continued to look a picture of confidence as he glided around the ring firing off classy shots. Steele’s progress was checked once more as he was struck by a hard right and a left to the stomach, and nobody could have foreseen the thunder and lightning that was to follow from the champion in the electric fourth round.

The roof caved in on poor Ken Overlin with shocking suddenness. Finally, Steele saw the chink of light he had been waiting for and unleashed a devastating combination that left Overlin in no man’s land. A big left to the chin staggered Ken and a similar blow set him falling. Two more terrific lefts to the chin from Steele caught Overlin in mid-flight and provided the coup de grace. It was a classic, stunning knockout.

Overlin crashed down on his back and rolled onto his face before bravely rising to one knee and clinging to the bottom rope as referee Tommy Clark counted him out.

Halcyon

It seemed in those halcyon days of his raging prime that Freddie Steele could not be derailed. Then he ran into a wall. All at once the gods seemed to rain on the poor kid with everything they had.

A broken breastbone and the sudden death of his beloved mentor, Dave Miller, were massively contributing factors in the story of an unstoppable fighter suddenly losing his way. But perhaps other little devils were at play too. In these much softer and more cushioned times, we tend to forget how often men of Freddie Steele’s calibre fought, how many remarkably hard fights they had and how suddenly the accumulative punishment could abbreviate their careers.

Even the toughest of men have a breaking point. If their durability doesn’t expire, then their desire does, however sub-consciously.

Whatever the reasons for his sudden decline, Freddie Steele met old foe Fred Apostoli again in a non-title match and got sucked into a brutal and unforgiving maelstrom. Freddie was stopped in the ninth round of that 1938 battle at Madison Square Garden, and by the time he staggered from the fray his breastbone was broken and his face horribly misshapen.

Dan Cuoco provides this newspaper report of the brutal fight, which graphically illustrates its savage intensity: “Blood came in a cascade from Freddie Steele’s left eye, the right was just a slit and in the middle of his face was a ring of red where once a nose had been. At times he was bent double, like a small boy peering through a knothole in a fence. That was the lurid scene, as presented before 8,000 spellbound witnesses at Madison Square Garden last night, when mercifully they stopped the fight after 54 seconds of the ninth round to save the middleweight champion of the world from further punishment.

“It was one of the wildest, most boisterous evenings ever put on at the Garden. For sheer savagery there have been few fights like this one. They faced each other with lips curled back in a snarl and belted each other ceaselessly with both hands. It was the greatest middleweight fight seen around here in a generation, topping even the Greb-Walker brawl by many a sanguinary punch and of course, will have to be repeated outdoors next summer, this time with the title riding along.”

Steele and Apostolic never did meet again, which was probably just as well for Freddie. The end was nigh for the thrilling Tacoma Assassin. He bounced back admirably to retain his world title with a seventh round stoppage of Carmen Barth in Cleveland, but now the hard fights and a troubled mind were taking their toll on Freddie. He had another tough one in capturing a decision over hard man Solly Krieger, before the big bomb finally dropped out of the sky. It was delivered by a devil of a natural puncher in the intimidating Al Hostak. Freddie was all out of steam by the time he defended against Al at the Civic Stadium in Seattle in July 1938. A disappointed crowd of 35,000 witnessed the quick execution of a fine champion Still recovering from his breastbone injury, which hampered him from holding his guard at a safe height, Freddie was also drained of motivation following the sudden death of Dave Miller.

Such handicaps were simply too much to overcome against an ambitious, major league hitter of Hostak’s class. Al brought the curtain down in the opening round and the top-flight career of Freddie Steele was over.

Ain’t Human!

Now then, how many other fighters turned successful actors would consider giving it all up to sell whiskey?

Here is writer Oscar Fraley from 1945: “Freddie Steele, the former middleweight champion turned actor, just ain’t human. With the manpower crisis reaching the point where the gals sigh and swoon in front of men’s haberdashery shops, the handsome and well-built Freddie wants to leave Hollywood’s panting pulchritude and go to Alaska as a whiskey salesman.”

Freddie, who always had an eye for business and had already owned a cigar store, was impressed by the news coming back from his folks in Juneau that they were doing great business at their drinking emporium.

Steele was thirty-two and described by Oscar Fraley as a smaller edition of John Wayne. Freddie was enjoying a very successful acting career, but there were drawbacks.

He had to grow a beard for his part in The Story Of GI Joe, which led to some baiting when he stopped off at a restaurant. A couple of mischievous characters kept giving him the eye and sniggering.

But there was no booming left hook from Freddie in the exchange that followed. “What’s so funny?” Steele asked.

“Your face with those whiskers,” one of the guys replied.

“Well, perhaps, but anyhow I’ve got it over you,” said Freddie. “You see, I’ll be able to shave this off. But you two have to stand behind those faces the rest of your life.”

Mike Casey is a boxing journalist and historian. He is a member of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO), an auxiliary member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and founder and editor of the Grand Slam Premium Boxing Service for historians and fans (www.grandslampage.net).