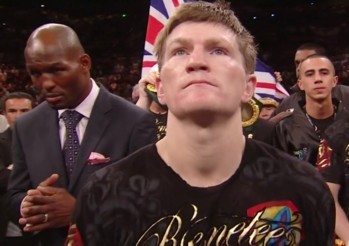

By Michael Klimes: You might disagree with the title of this article and ask, “How is it that Ricky Hatton is strange?” If anything this north Englander should be considered as one of the most grounded and sensible boxers on the planet, which is impressive considering the fact that there are many athletes who do not have the same following, adulation, money and celebrity that he does yet their real professions are breaking and gaining records in activities they should not be part of. The litany of sins includes arrests, prison sentences, affairs, divorces, rapes, assaults, public disorders, drug abuses, alcohol binges, and suicides and in exceptional cases the outright bizarre. The luminous sage in this section is former British sports presenter David Icke, who believes that the world has been conquered or is being taken over (I cannot remember which) one by giant lizards disguised as humans..

By Michael Klimes: You might disagree with the title of this article and ask, “How is it that Ricky Hatton is strange?” If anything this north Englander should be considered as one of the most grounded and sensible boxers on the planet, which is impressive considering the fact that there are many athletes who do not have the same following, adulation, money and celebrity that he does yet their real professions are breaking and gaining records in activities they should not be part of. The litany of sins includes arrests, prison sentences, affairs, divorces, rapes, assaults, public disorders, drug abuses, alcohol binges, and suicides and in exceptional cases the outright bizarre. The luminous sage in this section is former British sports presenter David Icke, who believes that the world has been conquered or is being taken over (I cannot remember which) one by giant lizards disguised as humans..

Therefore, Hatton is anchored in a sensible persona but the peculiarity of Hatton presents itself in judging his career: is he a lucky journeyman or a genuine world class fighter that should be regarded as only falling short against the two best opponents he has ever encountered? HBO commentator Larry Merchant and boxing analyst Steve Kim discussed Hatton’s stature before his tussle with Manny Pacquaio on maxboxing.com and a startling description came out of their conversation. The description is “a glorified version of Arturo Gatti” and it could characterise Hatton succinctly. However, Merchant and Kim could not quite find safe ground to stand on when they were attempting to pin a definition on Hatton as they both concurred that he would have his lasting reputation heavily decided by how he performed against Pacquaio.

Hatton, as we all know, was brutally outclassed. Freddie Roach, who has been predicting the outcome of bouts with unerring precision recently said that the counter-right hook he had been perfecting with Pacquaio in the Wild Card gym would be the defining punch of the fight. It did indeed operate with optimum efficiency. Roach’s assessment of Hatton was that he was one dimensional and could not change his style: when Hatton got hit by Pacquaio Roach claimed; he would immediately forget any refinements he had worked on in his preparation and would attempt to do what he always does and that is maul and brawl his way to victory. Indeed, this happened. A similar scenario, albeit a longer lasting one, transpired in the bout against Mayweather where Hatton’s technical sloppiness was simply not up to the task of dissecting his adversary’s surgical brilliance.

The debate over Hatton’s accomplishments and whether his style of fighting is ugly and boring or exhilarating and with design goes to the core of the way fans, historians and journalists rate fighters and how these labels we put on boxers and each other can co-operate and conflict. In comparing Hatton to Mayweather, we had the classic brawler versus boxer scenario and the pattern of the fight which unravelled in the minds of fans worked itself into reality as Hatton attacked and Mayweather boxed. Those who rooted for Hatton and those who supported Mayweather said as much about themselves as their fighters and what they value in them.

In his timeless and finest boxing essay ‘Ahab and Nemesis’; A.J. Liebling articulated the types of competing preferences that existed between Archie Moore, Rocky Marciano, the audience and himself. Liebling saw Moore as the snobbish intellectual with his dazzling style and Marciano as the ‘crude’ yet tough stalker. Liebling, in his dashing prose could not help but elevate himself with righteous deference above the crowd and I partially love him for it, “The crowd, basically anti-intellectual, screamed encouragement. There was Moore, riding punches, picking them off, slipping them, rolling with them…” W.C. Heinz, whom I also adore, had a much crisper, sharper and less digressive tone in his writing and the varying approaches Liebling and Heinz took to writing about boxing and how readers can respond to them is similar to boxers and boxing fans.

Here, I am not saying here that Hatton is Marciano and Mayweather is Moore but the same philosophical dispute applies. Hatton is admired and respected by his fans for being able to take a punch, as is his ballooning between fights as it shows, “he is one of the lads” to use a British phrase and does not take himself too seriously and has a sense of fun. The self-irony, which allows self-modesty and his sense of humour, that permits the witty one liner, essentially polite incivility, are two very English specialities. Hatton’s fighting style is in part a reflection of his upbringing, education and values. Furthermore, even though he could not compete successfully with Mayweather in the ring, he easily won the war of words as his funny cleverness came off as classier than Mayweather’s vulgar brashness.

The same, I think, is true of Mayweather as he is the opposite of Hatton as are his fans. Mayweather’s followers emphasise his ability not to take a punch as a sign of his skill and his discipline between fights as a signal of his seriousness and professionalism. I am not sure how to qualify Mayweather throwing a bundle of dollar bills into the camera as that does not seem to encourage love from anybody. Mayweather always talks about his scientific boxing while Hatton always mentions his strength and aggression. Ultimately, being a fighter is like being a writer, it is something you are and not something you merely do and that is why a lot of literature about boxing examines the relationship between character and the style of a boxer. How else does one explain Hemingway’s and Mailer’s infatuations with boxing as the fascinating dialectic in boxing is like that of writing: how does a writer define their writing and how does it in turn define them?

Back to classifying Hatton then, I feel Hatton is hybrid between a journeyman and world class fighter. He is undeniably brave, his way of fighting does have a method and he demonstrated a degree of élan against Paulie Malignaggi, Ben Tackie and Eamonn Magee. Remember how he surprised pundits against Malignaggi with his cleaner punching and occasional grappling which broke the role they had tried to mould him into. He also beat a declining Kostya Tsyzu in a way nobody thought possible and went over to America to fulfil his dream of becoming the best pound for pound boxer in the world. His following was also so large that he not only became the face of British boxing, he became one of the faces of boxing itself and as he himself correctly acknowledged: what price do you put on such loyal fandom?

Nevertheless, his technical limitations and lackadaisical attitude to his drinking and eating between bouts cost him. Obviously, I cannot say by how much and it was part of Hatton’s effusive charm that he was ready to have a drink with the common man that contributed to his marketability. However, boxing is a serious business and a serious art and after all the witticisms have been delivered I cannot take Hatton as seriously as fighters like Bernard Hopkins, Marvin Hagler or Floyd Mayweather Jr that have unstinting professionalism.

Still, as I have tried to demonstrate, any conclusion one draws about a fighter depends on one’s value system which is by no means objective. It is crucial to identify and recognise that stereotypes of fighters can both be enabling and disabling in our evaluations of them. The truth of people and boxing is usually more complicated than we like to admit.

MICHAEL KLIMES