by Pavel Yakovlev – This summer the WBC will hold its “Night of Champions 2010” event in Cardiff, Wales. The selection of the festival’s host country, as is well known, is due to Wales’s long and rich boxing history. In this article – subsequent to “The Luminaries of Welsh Boxing History: Part One” — Eastsideboxing continues its study of Wales’s boxing greats, focusing on the careers of Freddie Welsh, Dai Dower, Eddie Thomas, and Joe Erskine.

by Pavel Yakovlev – This summer the WBC will hold its “Night of Champions 2010” event in Cardiff, Wales. The selection of the festival’s host country, as is well known, is due to Wales’s long and rich boxing history. In this article – subsequent to “The Luminaries of Welsh Boxing History: Part One” — Eastsideboxing continues its study of Wales’s boxing greats, focusing on the careers of Freddie Welsh, Dai Dower, Eddie Thomas, and Joe Erskine.

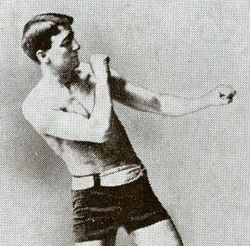

FREDDIE WELSH

World Lightweight Champion 1914-17

Pontypridd’s Freddie Welsh is regarded by many pundits as one of boxing’s all-time great fighters. Standing 5’7” and campaigning chiefly in the featherweight and lightweight divisions, Welsh dominated his foes with a brilliant left jab and nearly flawless technical boxing skills. During his 17-year professional career, Welsh accumulated a record of 74-5-1 (33 kayos). If newspaper decisions are included, Welsh’s overall record stands at 122-27-18 (33 kayos)..

As for Welsh’s boxing style and abilities, Greg Paterson of www.boxrec.com described the great champion as “a boxer of the highest caliber, he used excellent skills to perfect the age old objective of boxing ‘hit and not be hit’. The epitome of clever boxing, setting up his attacks with clever feints and bringing opponents onto counter punches with deft movements all wrapped together with a superb left jab that let him control his opponent like a matador controls the bull.” Also, according to Paterson, Welsh had “a slight hint of American style boxing which was rare for a British fighter at the time. Welsh could fight in close and liked to do it but still used tricky movement and angles to get himself into position to punch and set up counter shots with his brilliant feints.”

Unlike other Welsh boxers of his era, Welsh grew up in relative affluence. The son of a successful businessman, he took up boxing for recreation and fitness. Stricken by tuberculosis as a boy, Welsh recovered from his illness but remained weak and sickly. Welsh’s parents hired a physical fitness instructor to help him regain strength, and he quickly demonstrated virtuoso boxing ability. Welsh soon debuted in the fairground boxing booths, fighting frequently and impressing crowds with his talent, tenacity, and skill. Interestingly, Welsh’s grandfather had been a successful “mountain fighter” (unsupervised free-fighting) at Welsh fairgrounds. Excellence at combat sports was clearly a Welsh family trait.

Not surprisingly, Welsh grew into a restless and adventurous adolescent. Fearlessly, he moved to the United States — by himself — at the age of 16, surviving by taking odd jobs. Inevitably Welsh decided to supplement his income by fighting professionally. In 1905, he fought his first recorded match when he kayoed Young Williams in Philadelphia. Welsh then fought 26 bouts before returning to England in 1907, where he won thirteen fights and fought one no-decision. The no-decision was notable because of the opponent, none other than the great Jim Driscoll (47-1-4; 31 kayos). The pair fought a historic rematch six years later.

In 1907 Welsh began another tour of the United States, winning 17 bouts, losing once, and fighting four draws. The lone defeat was a decision against Packy McFarland (46-0; 34 kayos) in Milwaukee. The pair fought a draw in Los Angeles several months later. Welsh’s career took a dramatic upward turn in 1908 when he decisioned world featherweight champion Abe Attell (51-4-15; 23 kayos) in a non-title fight.

Back in England in 1909, Welsh won his first major title by stopping Henri Piet (record unavailable) in twelve rounds for the European lightweight championship. Several months later, Welsh acquired the British lightweight title via a twenty round decision over Johnny Summers (72-10-20; 27 kayos). Welsh’s future now seemed limitless: possession of the British and European belts, in addition to his victory over Attell, distinguished the young Welshman as a potential future world champion.

In 1910, Welsh fought two of the biggest bouts of his career. In London he battled Packy McFarland to a twenty round draw, the fight recognized as the British version of the world lightweight title. Afterwards, Welsh defended his European lightweight belt against Jim Driscoll. The much-anticipated bout took place in Cardiff before 10,000 fans, and Welsh won when the referee disqualified Driscoll for headbutting in round ten.

Welsh began 1911 with a loss, dropping a twenty round decision to Matt Wells (6-0-2; one kayo) in London. This setback cost Welsh his European and British lightweight titles. The following year, Welsh regained the British belt by outpointing Matt Wells (9-1-2; two kayos) in London. In 1913 Welsh won back the European championship when he kayoed Paul Brevieres in three rounds.

In 1913 and 1914 Welsh campaigned exclusively in the United States and Canada, fighting 22 times. During this tour he defeated future world featherweight champion Johnny Dundee (16-0-2; eleven kayos). Welsh won the bout over ten rounds by newspaper decision. In St. Louis, Welsh suffered a rare defeat when he was outpointed by Lockport Jimmy Duffy (19-0-3; 12 kayos) in eight rounds.

Welsh won the world lightweight championship in 1914, beating defending champion Willie Ritchie (22-6-12; seven kayos) on points over twenty rounds. The bout took place in London. In the following months, Welsh successfully defended his belt twice. He decisioned Matty Baldwin (85-23-51; 27 kayos) in Boston, then scored a ninth round kayo over future world champion Ad Wolgast (51-4-10; 34 kayos) in New York City.

After beating Wolgast, Welsh remained in America for three years. Amazingly, Welsh fought 49 times during this period — mostly no-decisions – as his title was not at stake unless the challenger won by knockout. The newspapers rendered their own decisions, however, and Welsh almost always emerged victorious according to the press. In 1915, he won and lost a pair of verdicts to Charley White (44-5-2; 27 kayos), and took the decision in their rubber match the following year. Welsh twice defeated Wolgast in rematches in 1916. In 1917, he won a twelve round decision over Battling Nelson (59-19-21; 40 kayos), the former world lightweight champion from Denmark. That same year, Welsh dropped a ten round decision to future world featherweight champion Johnny Kilbane (44-3-8; 20 kayos).

In 1916, Welsh fought two bouts against Benny Leonard (25-3, not counting newspaper decisions), who would later become one of the greatest lightweight champions in history. The first match took place at Madison Square Garden in New York City, and Leonard won the newspaper decision according to the New York Times. Several months later in Brooklyn, Welsh avenged the defeat by winning a newspaper decision over Leonard.

Leonard himself, in fact, finally ended Welsh’s reign as world lightweight champion. In May 1917, Leonard stopped Welsh in the ninth round, flooring the defending champion three times in the process. This defeat marked the first time Welsh was kayoed in his entire professional career. At age 31, his physical abilities were clearly eroding.

Welsh remained inactive for three years, then fought six times between 1920 and 1922. Clearly past his physical prime, Welsh struggled against mediocre opposition, winning four bouts, losing once and fighting one draw. The loss, a decision to Archie Walker (3-1; not counting newspaper decisions), convinced Welsh to hang up his gloves for good. Just five years later, Welsh died of heart disease at the age of 41.

DAI DOWER

British, British Empire, and European Flyweight Champion, 1930s

Dower fought a distinguished amateur career prior to turning professional. He won the ABA flyweight championship in 1952, and represented Great Britain at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki. Dower won two fights at the Olympics before losing a close decision to Anatoli Bulakov.

Dower then turned professional, kayoing Vernon John in four rounds. Two years and twenty consecutive victories later, Dower won the British Commonwealth flyweight title by outpointing Jake Tuli (24-3-1; 15 kayos) over fifteen rounds.

In 1955, Dower defended his Commonwealth belt by decisioning Eric Marsden (27-3-1; 13 kayos). Next, he won the European flyweight title by defeating Nazzareno Gianelli (21-12-8; five kayos) on points over fifteen rounds. But months later Dower lost the European belt to Young Martin (41-8-2; 24 kayos) by twelfth round kayo. The Welshman rebounded, however, and finished the year by outpointing Tuli in a rematch.

Dower traveled to Buenos Aires in 1957 to challenge the great Pascual Perez (40-0-1; 33 kayos) for the world flyweight championship. The combination of fighting in his opponent’s hometown and Perez’s great abilities proved too much for Dower to overcome, though. A single right hand knocked Dower out in the first round. The Welshman never again fought for a world championship.

Following the Pacual fight, Dower remained inactive for nine months. He returned to the ring in 1958, winning a decision over Eric Brett (11-5-1; six kayos), then finished his career with a points loss to Pat Supple (33-3-1; 18 kayos). Upon retiring, Dower embarked on a long and successful career as a physical education teacher at a grammar school and a university.

EDDIE THOMAS

British, British Empire, and European Welterweight Champion, 1950s

Merthyr Tydfil’s Eddie Thomas was born into a mining family in 1926; his father and six brothers pursued life-long vocations working underground. Thomas himself, in fact, continued laboring in the mines even after achieving success as a professional boxer. All of Thomas’s brothers boxed as well.

A masterful technical boxer with a sharp left jab, Thomas won the ABA lightweight title as an amateur in 1946, and then turned professional. Over the next two years Thomas won 16 of 18 fights before outpointing Gwyn Williams (46-10-1; 22 kayos) for the Welsh welterweight title. This victory was particularly sweet for Thomas, as it avenged a decision loss suffered to Williams only months earlier.

In 1949, Thomas scored important victories over Stan Hawthorne (59-7-3; 43 kayos) and Ernie Roderick (112-22-4; 45 kayos), both fights won on points. He then won the British welterweight title by decisioning Henry Hall (32-9-1; 16 kayos) over fifteen rounds. Thomas’s biggest victory of the year, however, was a ten round decision over American Billy Graham (76-3-6; 23 kayos) in London. The value of this victory is measured by the fact that shortly afterwards, Graham emerged as a long-term top contender.

Thomas fought seven times in 1950, winning six and boxing one draw. By the end of the year, Ring Magazine rated him fifth in its worldwide welterweight rankings. Given his high ranking and impressive professional record, now at 32-2-1, Thomas stood a serious chance of eventually getting a title fight with the great Sugar Ray Robinson, the reigning 147 lbs champion at the time.

The Welshman began 1951 by winning the British Commonwealth welterweight title with a thirteenth round kayo over Pat Patrick (17-1; seven kayos) in South Africa. One month later, Thomas captured the European welterweight championship by outpointing Michele Palermo (91-24-15; nine kayos). By the end of the year, however, he lost both belts; Charles Humez (46-2; 25 kayos) outpointed Thomas for the European crown, and the British Commonwealth title was lost to Wally Thom (22-1; 11 kayos) by decision.

Thomas remained inactive for almost two years following the Thom bout. He returned to the ring in 1953, but had only mixed success thereafter, winning four of seven fights. Thomas retired in 1954 with a career record of 40-6-2 (13 kayos). Subsequently, he became a prominent manager and promoter for several decades. Thomas made Wales the center of his promotional activities, operating independently of Mickey Duff’s operation in London, which dominated British boxing at the time. Among the prominent fighters managed by Thomas were Howard Winstone, Ken Buchanan, Colin Jones, and Eddie Avoth.

JOE ERSKINE

British and British Commonwealth Heavyweight Champion, 1950s

Renowned for slick boxing and defensive acumen, Cardiff’s Joe Erskine was described in Boxing Monthly as “probably one of the finest technicians in British heavyweight history.” Between 1958 and 1960, Ring Magazine continuously ranked Erskine as one of the world’s ten best heavyweights. Standing 5’11” and weighing 195 lbs at his peak, Erskine accumulated an overall record of 45-8-1 (13 kayos) during his ten-year professional career.

As an amateur, Erskine won an ABA championship in addition to winning numerous British military tournaments. He turned professional in 1954, and went undefeated in his first 30 professional bouts. During these years, Erskine defeated Henry Cooper (11-1; eight kayos), Dick Richardson (17-2-1; 14 kayos), and Johnny Williams (60-9-4; 38 kayos). The victory over Williams, a fifteen round decision in 1956, earned Erskine the British heavyweight title.

In 1957, Erskine lost for the first time, a first round kayo at the hands of dangerous Cuban veteran Nino Valdez (37-15-3; 30 kayos). Undeterred by this setback, Erskine rebounded by beating Cooper again, taking the British Commonwealth title on points in a battle of left jabs. Two months later, Erskine retained his title by outpointing Jamaican Joe Bygraves over 15 rounds. At this point, Erskine had won 31 of 33 professional bouts, and the Valdez loss appeared to be a fluke. The Welshman was ready for bigger challenges in boxing.

However, Erskine’s career took a temporary downward turn in 1958. First, Ingemar Johansson (18-0; 11 kayos) stopped him in thirteen rounds for the European championship. Erskine’s corner threw in the towel in the thirteenth round as he was under heavy attack by the Swedish power puncher. Several months later, Brian London (20-3; 17 kayos) kayoed Erskine in eight rounds. This defeat cost Erskine his British and British Commonwealth belts.

The dauntless Erskine regained stature the next year, however, by winning three straight victories, including a decision over world-rated American Willie Pastrano (47-6-5; 11 kayos). Later in 1959, Erskine challenged Henry Cooper for the latter’s British and British Commonwealth titles, but lost via dramatic twelfth round TKO. Despite this defeat, Erskine’s professional stature remained high, as Ring Magazine rated him the world’s number nine contender at the end of 1959.

Twice again Erskine challenged Cooper for the British and British Commonwealth titles, losing both times. Cooper stopped Erskine in five rounds in 1961, and beat him again in 1962, this time via ninth round kayo. These losses removed Erskine permanently from the worldwide top ten ratings. Nonetheless, in 1961 Erskine defeated up-and-coming Canadian George Chuvalo (20-6-1; 15 kayos) via disqualification in a Toronto bout.

In 1963, Erskine lost a decision to world rated Karl Mildenberger (37-2-1; 13 kayos) in Germany. Afterwards, Erskine outpointed Jack Bodell (15-3; nine kayos) and Johnny Prescott (23-3-2; 11 kayos), but lost a controversial decision to popular Londoner Billy Walker (12-3-1; nine kayos). Although just 31 years old and still a formidable fighter, Erskine retired from boxing after the Walker bout.