By Michael Klimes: When Chris Eubank went down on one knee in his second fight with Michael Watson in the eleventh round in 1991, he appeared to be a boxer completely outclassed. He had been surgically pummelled by a motivated and focused Watson. Then, Eubank mysteriously discovered a current of energy as he leapt to his feet and delivered the most devastating uppercut of his career. This infamous punch, which not only ruined Watson’s career but also his health, demonstrated Eubank’s greatest asset – his insatiable killer instinct. Eubank would finish Watson in the twelfth round but the subsequent fallout of the victory with Watson’s permanent brain damage and the evidence of what Eubank’s deceptive power could do changed him as a fighter and as a man. Consequently, Eubank did not show the same type of form in the ring or aura out of it for six years. Most importantly, he lost his ruthless ability to finish his adversaries when he most needed too.

By Michael Klimes: When Chris Eubank went down on one knee in his second fight with Michael Watson in the eleventh round in 1991, he appeared to be a boxer completely outclassed. He had been surgically pummelled by a motivated and focused Watson. Then, Eubank mysteriously discovered a current of energy as he leapt to his feet and delivered the most devastating uppercut of his career. This infamous punch, which not only ruined Watson’s career but also his health, demonstrated Eubank’s greatest asset – his insatiable killer instinct. Eubank would finish Watson in the twelfth round but the subsequent fallout of the victory with Watson’s permanent brain damage and the evidence of what Eubank’s deceptive power could do changed him as a fighter and as a man. Consequently, Eubank did not show the same type of form in the ring or aura out of it for six years. Most importantly, he lost his ruthless ability to finish his adversaries when he most needed too.

Donald McRae, in his edgy and spellbinding account of boxing in the 1990s, Dark Trade: Lost in Boxing, remarks towards the end of book that he no longer considered Eubank as a great fighter as he increasingly won a series of dubious decisions against second-rate opponents.. Compounding these dismal performances were Eubank’s lack of seriousness in his training and evolution into an eccentric yet amusing celebrity. However, the book ends, if I remember correctly, in 1997 and this was the year that Eubank went on what I consider to be his greatest run as a fighter as he was involved in three magnificent struggles against two world class opponents. The run lasted less than a year, he lost all three fights and retired after them, but there is something inspiring and even moving about Eubank shedding his glossy image and becoming a disciplined fighter for one last time. There are many fighters that have more accomplishments and are greater in stature than Eubank, who would have wished to leave the sport so well; Oscar de la Hoya being a fine example.

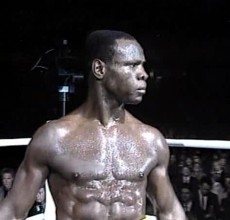

The context of Eubank’s resurgence is worth recounting as it makes his achievements all the more impressive. The gifted Welshman, Joe Calzaghe, was scheduled to fight the brawler Steve Collins, who up to that point in time was the only man to ever defeat Eubank twice, for the WBO super middleweight title in 1997. Collins decided to retire rather than confront Calzaghe. Eubank was then parachuted in as a replacement. He did not have much time to prepare for the contest, was thirty-one-years of age and based on his performances of recent years would be easy to beat. Nevertheless, a degree of hype entered the predictions of the bout as the more perceptive commentators acknowledged Calzaghe’s undefeated record and athleticism against Eubank’s experience and legendary toughness would make a sparkling clash possible. Both would give Calzaghe problems and fans were treated to a searing twelve round battle.

Calzaghe gained the momentum of the fight early on as he knocked Eubank down and maintained his phenomenal work rate for the first half of the fight. His windmill style gave Eubank problems as Eubank could not match his challenger punch for punch. This was partially due to older age but also due to Eubank’s more relaxed style of boxing, which flourished when opponents would come towards him and he could pick them off with his hand speed and awkward angels. The trouble was that Calzaghe was both tremendously fast and prodigious in the amount of punches he threw.

Nonetheless, Eubank knew his chin and conditioning would give him a chance to counter-attack later on once Calzaghe slowed due to tiredness. Inevitably, that happened and Eubank was able to land some excellent punches in the later rounds.

Unfortunately for him, he was unable to steer the direction of the contest away from Calzaghe and so he lost a unanimous decision.

Still, Eubank had proven he remained a world class boxer with the ability to compete at the highest level and entertain fans with his courageous spirit. Many wondered what his next move would be and he decided to go north in 1998, jumping up two weight divisions and twenty-two pounds in an attempt to become a champion in three different weight classes at cruiserweight by fighting for a world title. If this did not sound difficult enough, his first opponent was the formidable Carl Thompson, who might have been even tougher than Eubank himself. However, Eubank was not doing anything out of the ordinary as the audacious enterprise fitted into the pattern cemented from the beginning of his career of being able to continuously surprise the audience put in front of him. After all, he regarded himself as the consummate entertainer and his two encounters with Thompson were dazzling.

The first was probably the best and finest performance of Eubank’s distinguished career. Eubank executed a well defined plan of being elusive and quick as Thompson used his greater size and physicality to close his opponent down. Questions of how much stamina and power Eubank would draw upon were question marks above his head before the bout yet he answered them superbly. He staggered Thompson in the second and knocked him down in the fourth. Eubank peppered Thompson with fine jabs, blistering rights and worked in his uppercut beautifully during the fight. He also alternated between the head and body well, attempting to slow Thompson down early on so he could box at range more comfortably in the later rounds and dictate the bout at his own pace. However, his left eye began to close from the fifth round, which would prove decisive as his reflexes were not quite what they once were and he could not avoid punches as much as he used to. The eighth and ninth rounds were excellent as Eubank ran out of space to run and Thompson imposed his style of warfare on Eubank. Both engaged in an epic brawl and Thompson landed many straight rights and right hooks behind his accurate jab.

The final round was exhilarating as Eubank came out swinging and looked to sway the judges by reproducing some of his earlier mobility but it was all a bit of an illusion as Thompson, although not as a good a technician, had done the more solid but less sensational work. Eubank lost a unanimous decision but had done enough to earn a rematch, which was like the first fight but lasted for nine rounds instead of twelve. Eubanks’s left eye and Thompson’s right hand was again his nemeses. They could not quite generate the magic of the first contest.

The most unique of boxing personalities had finally finished his career that had begun in the Bronx but ended in Sheffield. Ironically, Eubank’s losses endeared him to the British fans in a way that his prime years never had done as he became more of an underdog and displayed more passion in his last fights than most of his fourteen defences at super middleweight. To me, he was a more likeable, mature and committed boxer at the conclusion of his career than in the middle when there was a lot of nonsense from Eubank with his celebrity chutzpah. Predictably, I find his first outing with Thompson to represent the best of boxing. What is surprising, however, is that I find Eubank, for all of his flaws, an endearing and even an exemplary figure in these three contests. He really was the best of himself at the end of his career and how many boxers can say that?