By Matt McGrain: Jimmy Carroll was born in Lambeth, London, seemingly in 1852, six years before the great John L Sullivan. Carroll was not unlike Sullivan in many ways, most notably in the sense that he was a born fighter but also in the sense that he bridges the gap between bare-knuckle and gloved boxing, straddling both eras with ease. Throughout the early 1870’s he first fought in fairgrounds and the brutal booths before graduating to the quasi-organised world of gloveless fighting, a cruel combination of boxing and wrestling.

By Matt McGrain: Jimmy Carroll was born in Lambeth, London, seemingly in 1852, six years before the great John L Sullivan. Carroll was not unlike Sullivan in many ways, most notably in the sense that he was a born fighter but also in the sense that he bridges the gap between bare-knuckle and gloved boxing, straddling both eras with ease. Throughout the early 1870’s he first fought in fairgrounds and the brutal booths before graduating to the quasi-organised world of gloveless fighting, a cruel combination of boxing and wrestling.

Carroll excelled. For obvious reasons, sources are scarce but the boxing scribe and former great American lightweight champion Billy Edwards describes Carroll as “invariably the winner” in these often merciless encounters. The idea that Carroll emerged from a decade of bare-knuckle boxing unbeaten is a difficult one to believe but it is clear that he was held in high regard. Although Carroll may have visited America as early as 1878 and may even have boxed a draw with a young Billy Frazier, later to be a top contender of Carroll’s era, it was during his 1887 visit that he made his real mark.

Stepping off the boat, Carroll had behind him around fifteen years of some of the toughest boxing imaginable. He was 35 years old, and was about to prove himself amongst the hardest men in the country – and the world.

Proof of Carroll’s reputation can be found in the match made for him in early February of 1888 against Mike Daly. Daly was an established gloved contender who claimed a share of the world lightweight title at this time, and not the type of fighter an English pug tended to land coming off the boat. Carroll was different.

The fight itself was a near disaster and absolutely made him as a top contender, the type of thrilling battle that appeared in American pulp fiction. Here was a fighter that could deliver such thrills for real. As we will see, Carroll was a boxer first, a defensive specialist second and a slugger only third and only when necessary. He started his fights slowly and measured his man for the kill, but here his plan was changed for him. Daly rushed Carroll immediately but the Englishman dropped his shoulder and cleverly moved out of the way, countering Daly’s body blows with left jabs and hooks. Carroll had an excellent and oft-used hook, which was not always the case for fighters brought up without the protection afforded by gloves, the easiest punch with which to break the hand. Carroll adapted his style quickly.

These punches were not enough to keep Daly off him here though, and he was dropped by a stunning right hand less than a minute into the first. Regaining his feet at a count of two, he was swept immediately back to the canvas by a long uppercut and making it out of the first became a desperate struggle for him. Before the second, one of the seven-hundred sports in attendance had to bet $10 on Daly to get $1 in return.

In his corner, Carroll spat blood. Daly was likely the best fighter he had ever met, but Carroll had been in worse spots than this. Toughing it out when hurt was as much a part of his life experience as breathing. It might be natural for a modern observer to see what Carroll was about to experience as a hell of his own making, but for Jimmy it was just another day at the office.

In the third and fourth The New York Sun describes Daly as landing “blow after blow after blow on [Jimmy’s] head, neck and ribs.” In the fourth, Carroll staged what would be the first of many rallies, landing his first real punches since the first, his superb uppercut which he had mastered with both hands, But these “failed to offset the repeated blows sent home by [Daly].” Carroll was nearly out in the fifth as a savage inside exchange and the first clinch of the fight was broken by “a sledgehammer of a right hand” which hand Carroll clinging desperately to the ropes. Carroll rallied again in the seventh whilst shipping terrible punishment to head and body but it was not enough. Daly took total control in the eighth and beat Carroll savagely to the end of the thirteenth by which time Carroll’s face “looked like a piece of pounded beefsteak.” Daly had two rounds left to close the show. If no knockout occurred, the referee had made clear he would call the fight a draw. Daly had won every single round but was looking at nothing more than a share if he couldn’t find the knockout blow in the next six minutes. He steamed out at the beginning of the fourteenth like it were the first.

Daly jabbed to the face and Carroll’s nose began to pour. He followed up with a right hand to the point of Carroll’s jaw and the Londoner floundered on the ropes once more. The unbreakable Londoner stumbled back out for the final round, Carroll threw two light blows to the body and then feinted another before snapping out that uppercut which landed right under the American’s chin. Daly squatted neatly, then sat firmly on the canvas, half-out. The referee began his long count. The New York Evening World claimed the count ran “twenty-five seconds”, to the end of the round. The New York Sun which had a man ringside claimed that it the Daly “did not gain his feet again until the full ten seconds had expired.” Jimmy Carroll himself made the count about fifteen seconds.

Whatever the specifics, Daly was on the deck for more than ten seconds and had to be helped to his corner with one round of the contest left to fight. It was a battle of its era, with all that entails. A fight that would have been stopped once for each round were it fought in a modern ring had been allowed to pursue its natural course to a grandstand finish but that finish too would be governed by the foibles of the time. As Carroll and Daly met centre ring and exchange furious punches in search of a knockout, the police entered the ring and waved the contest off.

“Gentlemen, you will have to select some other place to settle this little dispute.”

A draw.

The reaction to the fight was a sensation. The New York Sun declared it “the hardest fight ever seen in Boston.” Mike Gleason declared it the “best prizefight I have ever seen.” The clamour for a rematch was deafening. The two were matched over six rounds only a few weeks later, but it failed to measure up. Although a “fast and exciting affair” it was fought more carefully by both and Daly never really got near Carroll who boxed cleverly. Although they fought hotly in the last two frames, the inevitable draw was rendered. The two would never meet again.

The aftermath was predictable though. The aptly named “Ironman” Daly crowned Carroll the “best man I ever met.” This was no small praise. Daly was coming off knockout victories over Frazier and Meehan, top men at that time, and had just thrashed Jem Carney so badly in an exhibition that their scheduled fight had been cancelled. More importantly though, Daly had recently been pulled from an exhibition fight with the great champion Jack McAuliffe having apparently winded the champion with a bodypunch that the champion’s people had found unacceptable. Mutterings began concerning a match between Carroll and McAullife.

Jack “Napoleon” McAulife had begun one of the ring’s greatest title reigns two years earlier when matched with the same Bill Frazier some sources have a twenty-six year-old Jimmy Carroll boxing a draw with some years earlier. Frazier, one of the countries most respected boxing “professors” was regarded as the best lightweight in the world at the time and it is often forgotten that McAullife was a heavy underdog taking the fight on very short notice. He toughed out the first twenty rounds of a finish fight to score the knockout in the twenty-first. He cemented his claim to the title in a blacksmith’s shop, knocking out the hugely tough John L Sullivan sparring partner Harry Gilmour, leaving only Daly’s tenuous and oft-ignored claim to the title out there. He was clearing up.

Whilst Carroll waited for his shot, McAuliffe knocked out Dacey (KO11), Collyer (KO2), Hyams (KO9) to show his punching power, and fought the legendary sixty-four round draw with perhaps the era’s best puncher, Billy Myer (later avenged by a fifteen round knockout) in a fight generally regarded as the most scientific seen up until that point. Many will claim that Jack Ryan or Jack Dempsey were the most scientific fighters of this decade but McAuliffe would be my own pick. He was a ring genius who rarely bothered to train for fights in boxing’s toughest era and reigned a stacked lightweight division for more years than almost any undisputed lightweight title holder.

Before meeting Carroll, “Napoleon” decided to avenge the insult against him by Daly, who had famously winded him in an exhibition nearly two years before. This, he did, out-boxing Daly so cleanly that he promptly retired upon the announcement of the draw. The planned finish fight was cancelled at the instance of special officers Conboy and Whitman and replaced by a fifteen round battle to be declared even if no knockout occurred. The Ironman boxed carefully for survival and a share of the $1000 prize. As early as the second Daly bled from the right ear which was targeted mercilessly by McAulife’s left hand lead of mixed jabs and hooks. The champion boxed imperiously, forcing Daly to miss again and again despite his conservative style, landing almost at will with left and right, but Daly “stood the pounding first rate” and the three-hundred strong crowd (each of whom had paid a prohibitive $10 fee) cheered him lustily. McAuliffe finally dropped his man in the thirteenth, but injured his left hand in doing so and although a fight finally broke out in the fourteenth and fifteenth McAuliffe “manifestly having the advantage” the combination of his injury and the hastily agreed upon rules made the draw inevitable. It fell to McAuliffe’s only peer in terms of boxing skill, Jack Dempsey to talk him out of retirement.

Carroll was now the only logical challenger, but few gave the old man a hope. Jimmy was now thirty-seven years old. To put this into context, thirty-two was considered ancient for a heavyweight in this era, and most lightweights were washed up before their thirtieth birthdays. Carroll’s showing against Daly had been inspiring and most considered that he had been cheated out of the knockout victory, but nor could it be forgotten how badly the Ironman had thrashed him before Carroll had so deftly picked his spot. McAuliffe, meanwhile, had won every round he had boxed against Daly in their most recent encounter and had lasted sixty-four rounds with the huge punching Myer – just where would Carroll’s chances come this time?

In the build up, boxing’s ever-present rumour-mill seemed to indicate a win for the champion also. Carroll was “over-trained” and “about forty years old” according to the Pittsburgh Dispatch, whereas the champion was “in the best of condition”, down to 138lbs a week before the fight, which was very unusual for him. Carroll had on occasion been forced to “running to the point of exhaustion” previous to some of his fights, spending two-hours at a time horsing up and down the highways and byways of whatever strange corner of the earth the less that strictly legal Police-Gazette belt had taken him to for his routine defences. Here, he was ready. Jack was a 2-1 favourite, prohibitive odds according to the Pittsburgh Dispatch as Carroll was “game and clever.”

“I feel excellent,” ‘Napoleon’ told the New York Evening World on the day of the fight. “I was nearly down to weight in the first week, but rain retarded the work. Both myself and my friends are disappointed at the betting.”

Indeed, the betting had dried up. The line had moved to 10-6, but there were apparently no takers and betting would remain slow until just before the first bell. Carroll was not phased:

“I was never better in my life. I feel strong and confident. Have been below the weight several days. I will have no excuse to offer should I lose.”

Boxing is unlike any other sport in that it is essentially one of character, of ego. Technical skills are crucial, physical condition and assets are paramount, but without that self-belief, without the heart and will to put oneself in harms way, these tools become useless. The fighter’s ego is what gets him to the end of the toughest fight of his career, more-so than what he has learned or what he is. This is what makes boxing so special. But often a fighter’s ego begins to write cheques that his body just can’t cash. History is full of old fighters telling a sniggering press that they are at their best, they have never felt better. Could it be true, even just once?

McAuliffe’s original strategy was to rush Carroll, just as Daly had done, but Carroll was ready and moved cleverly out of the way of McAuliffe’s attack. Jack persisted and had minor success late in the round, but Carroll was essentially in control, maneuvering whilst McAuliffe wasted energy seemingly hoping for an early return on his aggressiveness. In the second, it was Carroll who rushed but such was McAuliffe’s surprise that the Englishman was able to land repeatedly. Reclaiming himself, the champion went downstairs then upstairs with the right, Carroll reacted with a straight right hand to the jaw. They moved inside for the first time and trade punches, Carroll going downstairs and McAuliffe going up before Carroll was forced to the ropes where he ducked and firmly countered for the best punch of the fight. In the third they swapped body punches before some clever footwork tricked McAuliffe onto the fight’s first Carroll uppercut, a punch which clearly distresses the champion. He “returns to his corner looking pale. Carroll [looks] flushed, red and strong.” (New York Evening World).

McAuliffe found his range in earnest in the fourth and returned Carroll’s uppercut with interest. Although not something he stuck to religiously, McAullife would often fight more aggressively after a round he felt he had lost and he dud so here. It back-fired. Carroll returned to counter punching. “McAuliffe made a half dozen terrific lunges, all of which Carroll avoided by clever dodging.” (St.Paul Daily Globe)

Expecting aggression in the fifth, Carroll began to feint with his head, attempting to draw McAuliffe onto him. The champion went to his trusted left, but felt short. Again, Carroll baited him with small moves and head feints, and again McAuliffe fell short with his left, but this time Carroll snapped out his own left and McAuliffe was on the ground looking up.

He was down for only seconds and forcing the action furiously, but it was Carroll who was smiling at the end of the round. Two things had happened. First, Carroll had showed McAuliffe that he was in a fight, and however well he had trained, it was not one the champion had expected. Second, the title of Napoleon was up for grabs in this fight. The consummate general was being out-thought both in terms of range and tempo. What was to follow was an evolutionary battle of generalship as each man vied to keep one step ahead of the other. Each man would mix up their leads, their punch selection, attacks to body and head, even mixing up which of them would lead and which would counter, although generally it was Carroll who boxed on the backfoot. Which of the two evolved the quicker would often determine the winner of a given round.

What is unusual is that far from making each man pensive about swapping punches, the uncertainty led to a fast bout as each grew more and more determined to force their will onto the other. McAuliffe won the second phase of action, establishing a rhythm of leading from distance with headshots before coming to middle-distance with a body attack and then retreating. Carroll’s bag of bareknuckle tricks made him the superior man inside and McAuliffe wanted to maintain at least some form of distance. The champion’s advantage culminated in the eighth with Carroll receiving “a serious pounding”, mostly to the body, but in the ninth Carroll drew first blood, feinting in and then placing a small cut on McAuliffe’s forehead with a right hand shot.

Carroll changed things up in the tenth allowing McAuliffe success in return for his own, counter-punching on landed bodyshots with headshots and a new more aggressive pattern was temporarily set, with neither man clearly dominating. In the twelfth, the two men fell during in-fighting and when they regained their feet their aggressive duel turned into an all out war, “terrific slugging at close quarters followed until both men were very groggy.” (Fort Worth Daily Gazette) “Mac swings right and Jim sends in a right drive, downing Mac!” (The New York Evening World)

Carroll had dropped McAuliffe again. The champion came out in a fury in the thirteenth, dominating for two minutes before Carroll sent in the same right hand and McAuliffe was nearly downed again. McAuliffe had failed in boxing for the knockout and now he became more cautious. Still, he struggled desperately with the Englishman who managed to outland him and maul his way through to take get the better of the fifteenth round. Finally the wild start had caught up with the two men, and the pace slowed noticeably. McAuliffe was staggered perceptibly in the eighteenth, caught flush by a patent Carroll uppercut and again Napoleon changed up his strategy, boxing from the outside for Carroll’s body, “…but to little effect. Carroll feinted but did not lead.” In a blink they had gone from fighting a war to playing chess. On paper this is McAuliffe territory, but Carroll was doing just fine. His strategy now was to feint the champion out of position and land where he could whilst keeping him off balance, seemingly waiting for the Jack’s hot temper to get the better of him again. “The fight will undoubtedly be lengthy,” noted The New York Evening World, in the twenty fourth round. “Mac has showed no superiority over Carroll up to this time. Jim is very clever, his shifty ducking winning applause. Mac lands a left and a right on Carroll’s body and face. Carroll lands a left on Mac’s face.”

This is the recurring theme throughout the bout. Carroll forces “Mac” to lead with feints and shifts, tries to make him miss, does or doesn’t, and then retaliates, usually with the harder shot. It’s an extremely dangerous strategy because McAuliffe appears to be both the puncher and the faster man in the fight, but Carroll banked upon his defence and ringcraft, learned over perhaps as many as twenty long years fighting under two savage codes, to keep him out of trouble. Perhaps it can be likened to Pernell Whitaker’s strategy against the younger, stronger, more powerful De La Hoya. “I’m right here. Can you hit me?”

In the twenty-seventh, Carroll drove McAuliffe to the ropes. In the next, the champion hurt the challenger to the body. Carroll clearly took the thirtieth on rabbit punches and jabs.

“The next few rounds were generally in McAuliffe’s favour…[A]t the 38th round the men, while not strong, were both in fair condition…Carroll commenced to pound away at McAuliffe’s jaw. He reached his mark more than half-a-dozen times and Mac was evidently becoming dazed. He struck out weakly but Carroll would get away and come back with another jab in Mac’s face.” (LA Times)

McAuliffe looked to be on his way out in the next round when for a heart stopping moment an “ugly uppercut” staggered him badly but Carroll couldn’t get the finisher in and they fought on.

“In the forty-third round McAuliffe was plainly getting weaker and a number more blows on his jaw from Carroll’s fist did not improve his condition.” (St.Paul Daily Globe)

Jack McAuliffe is the greatest lightweight pre-Gans and one of the greatest fighters of the era. The stakes could not be higher for Carroll, who, in his late thirties, had surely already qualified himself as one of the great old men in ring history. Now he seemed one punch away form true ring immortality. Yet, few people today have heard his name. Of course Carroll’s own condition was deteriorating fast, but apart from rounds 30-38 he seems to have at least fought on even terms with the champion. How did McAuliffe pull the iron from the fire? Did Carroll make a fateful and tragic error? Or was McAuliffe just made of that rare and special stuff that only great champions can lay claim to?

“Carroll continued to gain the advantage, and in the next three rounds pounded McAuliffe on the jaw until it seemed the later would go out at any moment…at the opening of the forty-seventh round Carroll still acted on the aggressive…” (LA Times)

“Carroll still acted on the aggressive.”

Throughout the fight, even in moments of dominance, Carroll boxed carefully. He knew all along where he was headed – deep, deep water, deep enough to drown a 135lb giant – and he wanted his wits about him when he got there. So economy and defence were his mode of transport. “[McAuliffe] struck out weakly but Carroll would get away and come back with another jab.” This was the strategy that had got him into a position of total dominance against one of the most dangerous fighters in ring history. Now, he was the aggressor – he was going for the knockout.

“…Mac seemed to revive a little. The men were fighting hard at close quarters…finally Mac’s right hand came in contact with Carroll’s jaw and…[he] went down. He rose in three or four seconds, and Mac started in to finish him, though it was difficult to say which man was the weaker. Mac’s face was covered with blood but there was very little on Carroll’s. Mac finally caught Carroll on the mouth and sent him down on the floor with a thump. Ten seconds were counted off but there was still no movement of his body and his seconds had to carry him to his corner. Mac was declared the victor amongst the enthusiastic cheering of the spectators.” (The LA Times)

“I am not a newspaper fighter. That is not how I have made my reputation,” Carroll would tell reporters. This was true. He gave very few interviews. But he was vocal in demanding a rematch. Many in the press supported him. “Before the deciding blow was struck Carroll’s chances were even brighter than those of McAuliffe,” said The Pittsburgh Dispatch. “The champion knows he crawled out of a very tight aperture.”

Indeed, the two would be matched again, but not until McAuliffe had knocked out Austin Gibbons, Bill Frazier, avenged his draw with Bill Myer and added seven more wins including an astonishing win over Young Griffo – all whilst eating himself out of the division. No lightweight in the world could defeat him but his own questionable discipline finally let him down. By the time he and Carroll met again in 1896, although very much still Napoleon, he was fighting at between 145 and 150lbs, and hadn’t defended “his” world title in four years.

What of Carroll? A man of iron discipline, he hadn’t slipped even a bit. After McAuliffe he ignored the opportunity to retire with the great honour his outstanding effort had bestowed upon him and thrashed two of the era’s greatest contenders, knocking out Andy Bowen in twenty-one rounds and then Billy Myer in forty-three. But a fight with Jack never materialised and he did indeed drop from the scene. A comeback seemed ill-advised when he was stopped in a single round by Barbados Joe Walcott, another genuine ring immortal, but aged forty-two he showed some of the old form fighting a spirited draw with Andy Bowen (who would be retired in his very next fight versus one of the leaders of the new wave, Kid Lavigne). Two years later, aged forty-five or forty-six, he was finally matched again with Jimmy Carroll.

“After six years of patient waiting,” The Salt Lake Herald noted, Carroll was finally back in the ring with McAuliffe. “Although Carroll has passed his fortieth year,” said the Saint Paul Globe, “he is a well preserved man and has trained long and faithfully for this, perhaps his last fight. It has been said he has been in training for years to defeat McAuliffe and he entered in condition.”

In fact, Carroll was 135lbs, one half-pound lighter than he had been in 1890 for the first fight. McAuliffe on the other hand, had all but given up on the training he so despised. There was more now of the living legend to go around, about 150lbs worth. Carroll, “looking hard” was all that and more, but his time was up. The same age as George Foreman had been when he regained the heavyweight title, but with thirty years of the hardest kind of fighting behind him, Carroll was all but finished. For a moment, in the fifth, countering McAuliffe fiercely from his ropes he looked his old self, and in the eighth his treasured uppercut had Jack badly hurt, but he ended that round on one knee after being clipped with a hard right.

In the ninth, Carroll tottered from his corner looking “very weak.” McAuliffe was not a man to let a hurt opponent off the hook, and nor was he the type of man to take it easy on an opponent in the ring, but round nine was punctuated mainly by “ineffectual punches.” The tenth was worse, and according to The Saint Paul Globe it was “fought as a series of clinches.”

Perhaps McAuliffe, an old man himself by now in ring terms, had simply lost his stamina or his desire.

Or perhaps Jack held Jimmy in such high regard as to not want to do the old warrior any real harm.

It was not what Jimmy Carroll would have wanted, but it was no less than he deserved.

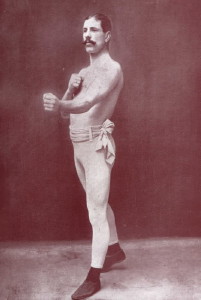

Two notes: Very few pictures of Jimmy Carroll seem to exist. If anyone has one they’d be interested in sharing, please contact me at m.mcgrain@hotmail.co.uk. Also, I’d just like to correct an error on Boxrec’s fragment of Carroll’s record. He didn’t lose to Jimmy Dime. That was a different Jimmy Carroll, a light-heavy who fought out of New York where he fought under the nickname of “Harlem Billy.”