By John Wight – “What is one million dollars compared with the love of eight million Cubans?”

By John Wight – “What is one million dollars compared with the love of eight million Cubans?”

These were the words of legendary Cuban heavyweight boxer Teofilo Stevenson in response to a lucrative multi-million-dollar offer to turn pro and fight Muhammad Ali after the Montreal Olympics in 1976.

They remain as powerful a testament to the nature and character of the Cuban Revolution today as they did when spoken over 30 years ago.

Today the word legend is bandied around so often in sport that it has almost been rendered devoid of meaning.

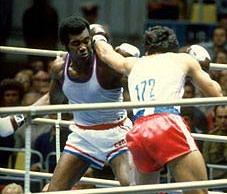

This isn’t the case, however, when it comes to describing Stevenson, a man who dominated world amateur boxing over a career that spanned 14 years and three Olympic Games, returning on each occasion with a gold medal to make him one of only three boxers to achieve this remarkable feat (one of the other two men to have achieved this feat happens to be fellow Cuban Felix Savon)..

To add to his haul of three Olympic golds, Stevenson also won three World Amateur Boxing Championship gold medals and a further two golds at the Pan American Games before announcing his retirement in 1986 at the age of 34.

Born in 1952 and brought up in Cuba’s fourth largest city Camaguey, the son of immigrant parents, Teofilo’s destiny seemed all but mapped out.

His father had been a boxer, fighting seven times before retiring in dismay at the corruption that was endemic in the sport in its pre-revolutionary era, and he had been endowed him with genes which provided him with the required physical attributes.

In fact, developing an early love of the sport, it wasn’t long before Teofilo junior was making regular trips to the open air gym where his father had trained, though without his mother¡¯s knowledge.

There he was taken under the wing of former Cuban light heavyweight champion John Herrera, who after matching him against a series of far more experienced opponents knew that the young Teofilo had what it took to go far in the sport.

During the mid sixties, Teofilo’s development under Herrera progressed rapidly after winning a junior title and then coming to the attention of Cuba’s newly created state sponsored boxing school, during a stint spent training in Havana.

Headed by former Soviet boxer Andrei Chervnevenko, the school would mark the beginning of Cuba’s outstanding achievements in the sport, earning Cuban boxing the world renowned status that it enjoys to the present today.

When the 20-year-old Teofilo stepped into the ring to mark his Olympic debut at the 1972 games in Munich, Cuba hadn’t won an Olympic gold medal since 1904, and that had been in fencing.

By 1972 the Olympic heavyweight boxing gold medal was felt by the US to be their property as if by right. Joe Frazier had taken the gold at the 1964 games in Tokyo, while George Foreman did likewise at the 1968 games in Mexico City. Incidentally, Ali’s gold medal at the 1960 games in Rome came in the light heavyweight division.

The US heavyweight representative at the Munich games was Duane Bobick, considered the favourite after taking the gold medal at the Pan-American Games in 1971, during which he had handed the still developing Stevenson a rare defeat.

The stage was set for a rematch when they were drawn in the third round of the Munich Olympics a year later. At 6¡¯3¡å tall and weighing in at 215lbs, Bobick looked every bit as physically impressive as his Cuban opponent.

Known as a hard puncher and a man who spent countless hours in the gym working on his skills, Bobick had arrived at the Olympics having defeated future heavyweight professional champion Larry Holmes to win the right to do so as US amateur champion. Given his prior victories over Teofilo and Larry Holmes, it was therefore no surprise that Bobick was expected to return home with yet another heavyweight boxing gold for the United States.

The fight lasted three rounds and was to be one of the most brutal of Stevenson’s career. In the first he took the fight to his opponent, catching Bobick with a left hook to send him stumbling back against the ropes on the way to winning the round.

In the second Bobick came out determined to make amends. Fighting most of the round on the front foot, he managed to pin Stevenson back against the ropes, where he attacked him with body shots and hooks to the head.

However, Stevenson’s strategy of allowing his opponent to punch himself out paid off, as by the end of the second Bobick had nothing left in the tank while Stevenson was still breathing normally.

In the third and final round, the Cuban handed his more prestigious US opponent a boxing lesson he and the world watching would not forget.

Utilising a punishing array of jabs and overhand rights, Stevenson proceeded to punch Bobick all over the ring. Such was his dominance in the third round of the fight that Harry Carpenter, commentating on the fight for the BBC, excitedly exclaimed: ¡°The legend of Bobick (is) absolutely being destroyed here’±

The fight ended when the referee finally stepped in to stop what by now was one way traffic to earn Stevenson, and Cuba, a famous Olympic victory.

Describing the Cuban’s emphatic victory over his US opponent in his book The Red Corner ¨C A Journey Into Cuban Boxing, the author John Duncan writes: ¡°It was a beautiful moment for Cuban sport, one in which you could sense a whole century of inferiority complexes melting away.¡±

Predictably, Stevenson again swept all before him at the Montreal Olympics of 1976 to claim his second gold medal. Once again he faced a US opponent, this time in the shape of John Tate in the semi-final, knocking him out in the first round.

The US team boycotted the 1980 games in Moscow in protest at the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, but there’s little doubt with his continuing dominance of the sport that Stevenson would still have claimed his third Olympic gold even if the US team had taken part.

In fact, the Cuban was only robbed of a fourth gold medal when Cuba boycotted the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984, along with the rest of the Communist bloc countries, in retaliation for the prior US boycott of the Moscow games. However, rather than bemoan another opportunity for glory, Stevenson announced his support for the boycott, describing it as an ¡°act of solidarity.¡±

Before he passed away, Teofilo maintained his passion for boxing in his role as vice-president of the Cuban Boxing Federation.

In 1999, as coach of the Cuban national boxing team, he was involved in an altercation at Miami International Airport on the way home with the Cuban team from an international tournament.

Stevenson retaliated after he and the rest of the team were subjected to insults and verbal abuse from anti-Cuban protesters. He was arrested, released on bail, and returned to Cuba. He refused to return to Miami for the resulting court proceedings into the incident.

A bona fide boxing legend, Stevenson also stands out as a man of immense pride and dignity, whose commitment to the ideals of the Cuban Revolution has not only seen him turn down the opportunity to enrich himself but has inspired millions around the world.